For a long time after the disaster, Mike Williams was haunted by the sound of helicopters.

On the night of April 20, 2010, Williams, the chief electronics technician on the Deepwater Horizon oil rig, barely survived a devastating blowout that claimed the lives of 11 of his co-workers. Trapped on the burning rig after a series of explosions, badly injured, Williams leaped nearly 10 stories into the Gulf of Mexico and was eventually medevaced to safety by a Coast Guard helicopter.

For months afterward, just hearing the whirring of helicopter blades would bring traumatic memories back.

“I had this deathly fear of helicopters for probably another two years after the accident,” Williams, 44, said on a recent afternoon by phone from his home in Dallas. “I could hear a helicopter in my sleep and wake up screaming. That was kind of a trigger mechanism that took me back there every time.”

Another Deepwater Horizon survivor, Caleb Holloway, says one of his own triggers in the intervening years has been the Christian hymn “How Great Thou Art.”

Working as a floorhand on the rig’s drill crew, away from home for weeks at a time doing physically demanding work, Holloway had the words of the song written inside his hard hat for inspiration. In the wake of the disaster, he heard it sung at memorial services for the men he’d worked alongside.

“Every time I hear that song, tears well up in my eyes and I get a lump in my throat,” Holloway, 34, said recently from Nacogdoches, Texas, where he now works as a firefighter.

Arriving in movie theaters just six years after the tragedy, director Peter Berg’s “Deepwater Horizon,” opening Sept. 30, sets out to dramatize the worst environmental disaster in U.S. history for those who only followed it on the news, leveraging all the cinematic bells and whistles a major Hollywood production can buy.

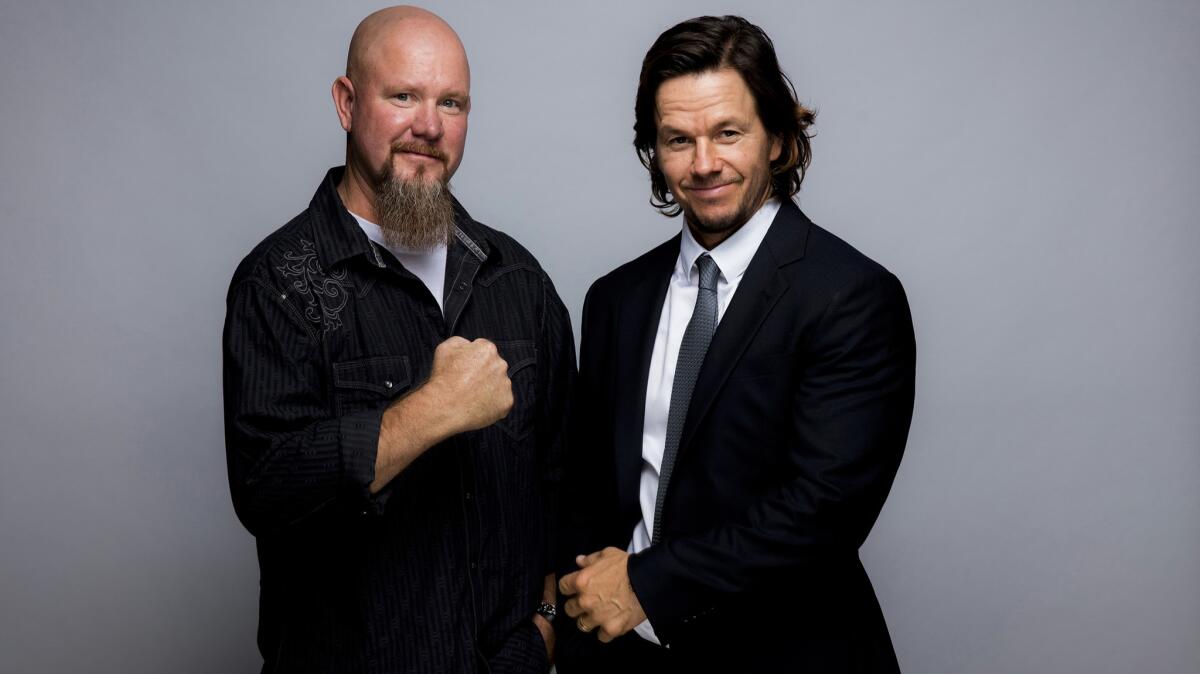

“It has those elements of a disaster movie but it’s a true story,” said Mark Wahlberg, who plays Williams in the film, which is being released by Summit Entertainment. “We didn’t want to paint by numbers — you have to make it as realistic as possible. I loved the studio’s courage to make a character-driven adult action movie where there’s no chance for a sequel.”

For Williams, Holloway and the other 113 men and women who lived through the catastrophe that unfolded 40 miles off the coast of Louisiana, the film represents something more personal: a way to pay tribute to their fallen co-workers and, perhaps, get some closure.

“I didn’t go looking for this,” said Williams, who served as an on-set consultant during production. “But I did accept the challenge of bringing this to the screen and getting it right to speak for my 11 brothers who can’t speak. … We need to tell the story the way it happened. If one single family member objects to this project on the merits — not on the emotional part of it but the merits — then we’ve failed.”

See the most-read stories in Entertainment this hour »

While real-life disasters have formed the basis for many Hollywood movies like “The Perfect Storm,” “Titanic,” “The Impossible” and “Everest,” bringing the story of the Deepwater Horizon to the screen presented its own unique challenges.

Explaining the cause of the blowout requires conveying a large amount of highly technical information and specialized jargon to mainstream moviegoers who may have only the vaguest idea of how oil is extracted from beneath the ocean floor and what life is like on an offshore rig. “It’s like the inside of an NFL locker room,” said Williams, who has left the oil industry since the Deepwater disaster and now runs a couple of small businesses with his wife. “You kind of know what’s going on in there but you don’t really know.”

At the same time, the intense government investigation, litigation and political debate that followed the Deepwater Horizon disaster make it more than a simple tale of survival and individual heroism. For 87 days after the blowout, millions of barrels of oil flowed into the Gulf of Mexico, causing widespread and lasting harm to wildlife as well as the tourism and the fishing industries from Texas to Florida. BP, which was found primarily responsible for the spill by a federal judge in 2014, has been subjected to billions of dollars in penalties and settlements on top of billions in cleanup costs.

Some survivors and family members of victims initially regarded the prospect of a film about the Deepwater Horizon with a degree of wariness. “I realize that somebody was bound to make a movie of it,” Patrick Morgan, who was an assistant driller on the rig, told the Tampa Bay Times last month. “I just don’t want to see politics and political correctness and all that crap play into it.”

But Berg says his aim from the start with “Deepwater Horizon” was to keep the focus squarely on the human story at the heart of the disaster.

“To this day, when people think of Deepwater Horizon, they only think of an oil spill — they think of an oil spill and dead pelicans,” said Berg, who took on the project after original director J.C. Chandor stepped away because of creative differences.

“Obviously that oil spill was horrific,” he continued. “But the reality is 11 men died on that rig and these men were just doing their jobs and many of them worked hard trying to prevent that oil from blowing out and it was certainly not their fault. As it pertains to the families of those men who lost their lives, I want them to feel as though another side of that story was presented, so that whenever someone talks about the Deepwater Horizon or offshore oil drilling, people don’t automatically go to ‘oil spills.’ ”

The basis for the film’s script, written by Matthew Sand and Matthew Michael Carnahan, was an exhaustively reported 2010 New York Times article on the Deepwater Horizon’s final hours by David Barstow, David Rhode and Stephanie Saul. Figuring out how to boil the sprawling story down to a manageable size was no easy task. But eventually the narrative centered on a handful of real-life figures, including Williams, Transocean offshore installation manager Jimmy Harrell (Kurt Russell), bridge officer Andrea Fleytas (Gina Rodriguez) and BP rep Donald Vidrine (John Malkovich).

While highlighting the management decisions that led to the disaster, the film deliberately tries to steers clear of any simplistic depiction of corporate villainy, according to producer Lorenzo di Bonaventura.

“In those kinds of events, there is no black and white,” Di Bonaventura said. “If you have an agenda, you’ll see this movie through your agenda. But it’s very important to us: It’s not an anti-oil movie. It’s not a pro-oil movie. It’s what happened that day.”

Every movie being released in our Fall Movies Guide »

A riveting 2010 interview with Williams on “60 Minutes,” in which he recounted his harrowing escape from the rig, helped give the story much of its emotional spine. But when Williams was first approached about the project, he was hesitant about being cast as any kind of hero.

“He was very nervous about what he called ‘stolen valor,’” Berg said. “He wanted to make sure that we didn’t present him in a way that made him look like he did a bunch of things that he didn’t do or was any more heroic than any other people on that rig. And I respected that.”

As one of the crew members most familiar with the workings of the rig — and one of the last to make it off of it alive — Williams was an invaluable resource, said Wahlberg. “Once I met Mike, I just insisted that they bring him on as a consultant,” he said. “I wanted him to be there with us and make sure we were getting it as accurately as possible.”

Working with a net production budget of roughly $110 million, the “Deepwater Horizon” crew built an immense 85%-scale replica of the rig in the parking lot of an abandoned Six Flags amusement park in Louisiana, using more than 3 million pounds of steel. Every detail of the Deepwater Horizon was re-created in painstaking detail — “all the way down to the salt and pepper shakers in the galley,” Williams said.

“It was actually a little eerie being on set,” said Holloway, who is played in the film by Dylan O’Brien. “It was almost like I wanted to go to work, it was so real. But my main goal was to ensure that everybody knew Shane [Roshto] and Adam [Weise] and Karl [Kleppinger] and the guys that passed away. I wanted the actors to know who they were on a personal level.”

Looking back on the tragedy, Williams, whose head smashed into a door when the rig was rocked by explosions, says it’s a miracle more people weren’t killed, himself included.

“Just bad weather would have increased the fatality rate by who knows how much,” he said. “I’m under no illusions — I should never have come out of my shock. After that door hit me in the forehead, I should have still been in there, laying on the bottom of the ocean. But I was too hardheaded, I guess.”

Like Williams, Holloway isn’t sure why he survived the Deepwater disaster when others didn’t. “The first year after this happened, I was continually asking, ‘Why?’ But it got to a point where I had to finally embrace it and just thank God for the time I got to spend with the guys who passed away.”

To this day, he still has the hard hat he wore on the Deepwater Horizon.

“Somehow I ended up with it at the end of the night,” Holloway said. “It’s one of those things I’ll cherish forever but it’s also hard to hold on to. It brings back the good memories as well as the bad.”