Neil Armstrong’s sons knew that Ryan Gosling was capable of playing their dad. He was an accomplished actor who’d been working since he was a kid and had twice been nominated for Oscars. Sure, they didn’t necessarily see the resemblance between Gosling and the late astronaut. But Tom Hanks didn’t look like Jim Lovell, and “Apollo 13” worked out just fine.

So the question Mark and Rick Armstrong really wanted to know when they first met Gosling was this: How committed are you to learning about our dad?

“I know he has the capability, because Ryan doesn’t have to work if he doesn’t want to,” said Mark, 55. “But did he really want to dig deep?”

“Playing dad is not an easy task for anybody, because he doesn’t give you a lot to really work with,” acknowledged Rick, 61.

From the moment the elder Armstrong set foot on the moon, the public has longed to know more about the man who made history in space. In the years following his 1969 moonwalk, he reportedly received 10,000 fan letters a day. But the famously elusive astronaut rarely granted interviews or attended public events commemorating the Apollo 11 mission. Instead, he decamped to a farm in Ohio, where he taught at the nearby University of Cincinnati. He never wrote a memoir, and it took his biographer two years to convince him to participate in a book about his life.

For his sons, the idea that yet another Hollywood production wanted to turn their father’s life into a movie was greeted with the usual skepticism. Not of the filmmakers’ credentials — director Damien Chazelle (“La La Land”) and screenwriter Josh Singer (“Spotlight”) are both Oscar winners — but of the possibility for any movie to get their father right. And that task would no doubt be the most difficult for the actor who wanted to play Neil.

The instant the brothers sat down with Gosling at Pacific Dining Car, a Santa Monica steakhouse set in a railway wagon, the 37-year-old started asking questions — “a lot of questions, and they kept coming,” Mark said. The initial inquiries weren’t that probing. But the more information the brothers gave the actor, they said, the better Gosling’s questions became.

“You could see that effort was going into this — that he was taking this seriously,” said Rick. “He was trying to figure out everything he could.”

The brothers’ cooperation would prove vital for “First Man,” which opens nationwide on Oct. 12. Because while the film delves into the danger behind the Apollo 11 mission, it also trains a lens on Armstrong’s private side. The movie looks at what life was like at home for his wife, Janet, and his two sons as he departed on his risky space travels and examines how Neil was affected by the loss of the family’s daughter, Karen, who died at age 2 from cancer.

And because of the intimate nature of the project, Gosling felt the blessing of Neil’s sons was essential. (Their father died in 2012 at age 82.)

“It all really began with them — did it feel right to them that I be doing this?” said Gosling, 37. “If I didn’t feel their support, I wouldn’t have done the film.”

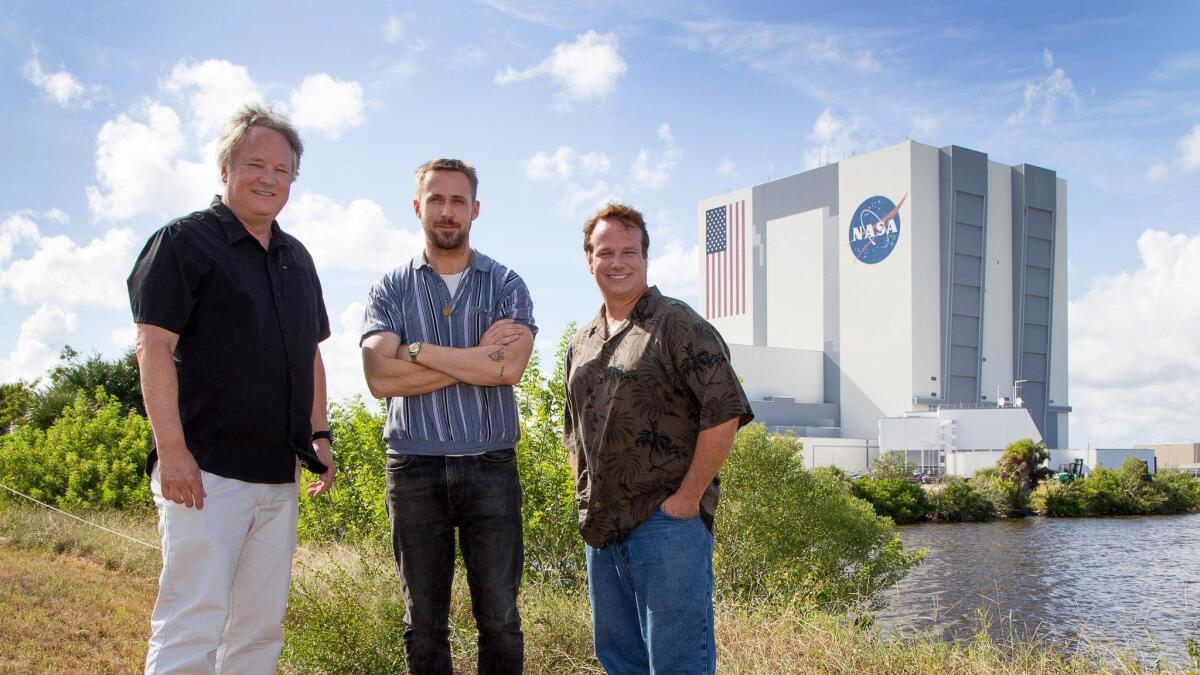

“We never would have said that, though,” Rick said, chuckling. He and Mark were sitting next to Gosling at the Kennedy Space Center last weekend in the shadow of NASA’s vehicle assembly building — the facility where the rocket that propelled Neil to space was built in the ’60s.

“I thought you would have,” Gosling insisted.

“No, I don’t think so,” Rick continued. “I remember people asking me when it first got announced: ‘Do you think Ryan Gosling can do this?’ Well, he’s an actor, right? It’s up to him whether he can do it or not. I’m not smart enough or perceptive enough ahead of time to go, ‘No, you’re not capable of that.’”

Ultimately, though, the brothers felt comfortable enough with Gosling to give the actor insights into their dad that even historians had trouble accessing. It took years for Neil to agree to meet with James Hansen, who wrote the 700-page book “First Man” is based on. Hansen couldn’t find a public address for Neil but was able to track down a P.O. box through a contact he had at NASA. When Neil finally agreed to meet the author in Cincinnati, Hansen said, he was told to “stay in this motel in this area and I’ll give you a call.”

“I had heard all these stories about him, that he was reclusive, he was cold, he hated the press and he just wanted to be left alone,” said Hansen, whose book was published in 2005. “So yeah, all of that built up a lot of nervousness on my part. But when I met him, it almost instantly went away because I found him to be very charming and sociable.”

That Neil had a reputation for being taciturn still bothers his sons, who feel their father has been largely misunderstood by the media. He just wasn’t wired to care about celebrity, Rick said.

Once, when the family was headed on a vacation during the 1970s, they got bumped off a flight. His sons begged him to use his clout to to get back on, but he resisted.“He finally went up to the counter, but only because we nagged the crap out of him and said, ‘Dad, dad, we gotta go!’” Rick recalled. “He was physically shaking. There was this internal struggle that you could just see in him, that he didn’t want to do that.”

The fact that Neil was such a private individual gave Singer pause about how much the film reveals about the astronaut’s personal life. Most of Neil’s closest friends didn’t even know he’d lost his daughter to a brain tumor.

“I don’t know how he would have felt about everything we’re exposing about him,” acknowledged the screenwriter. “I think about that on occasion. And yet, Rick and Mark, Janet — it’s their story as well.”

“I feel as though I did get to meet him, in some way.”

— Actor Ryan Gosling on Neil Armstrong

Not that Neil would have been opposed to the idea of a film being made about his life, Hansen noted. When Warner Bros. first bought the movie rights to the author’s book in 2003, Clint Eastwood was interested in the story and invited Neil to his private golf course in Carmel. Nearly a decade later, after the project had moved over to Universal Pictures, he met with the producers who would ultimately go on to make Chazelle’s film. Neil also invited two potential screenwriters to his home.

“And he would have done it with Josh, had Neil still been alive,” said Hansen. “It’s not like we were somehow doing something that he was unaware of. He was totally aware that this was happening and he was totally aware of what I had discussed in my book about his private life.”

Teasing deep-seated details out of Neil was painstaking, Hansen admitted. He cited one negative review of his book that ran in The Times and argued that he didn’t “get deep enough into Neil’s psychology. Well, good luck. Unless you can get him on a couch with a psychiatrist for months at a time, that wasn’t going to happen.”

ALSO: From ‘First Man’ to ‘Roma,’ Oscar season comes into focus at Telluride Film Festival

The majority of Hansen’s essential insights into Neil, he said, came from the women in his life: His wife, Janet — who died in June at age 84 — and his sister, June. Gosling was able to meet with both women in preparation for the role, but it was his trip to northern Ohio to meet Neil’s sister “that really unlocked something for him,” said Chazelle.

“I find there’s such a poet in Neil, and I was asking her where she thought that came from,” remembered Gosling. “She said their grandmother used to read poetry to him, and he felt he got that from her. She actually at one point just physically tried to embody him for me, so I could see how he would look at her or how he would listen to something. It was a beautiful transformation and it was filled with so much love — the love of a sister that only a sister has.

“It just became clear that everybody I was meeting — it was just so important to them that we get this right. They were meeting with us so that there was no information they had left out that the film could have benefited from, no matter how small it might be.”

Accuracy was prized by Neil, his sons said. Once, Mark and his dad went on a golf trip that had been scheduled by a tour group. But the reservation had been booked under a placeholder name, Johnson, instead of Armstrong — and Neil couldn’t stand to lie.

“We’re about to tee off and I look at dad and say, ‘What’s wrong?’” Mark said. “And he goes, ‘I don’t feel right about this.’ So he goes up to the starter and says, ‘I know we’re the Johnson group, but my name is actually Neil Armstrong, and I’m a member of the [prestigious golf club] Royal and Ancient. I just needed to tell you that my name’s not Johnson. I just felt like you should know the truth.’ And the starter looks at him and goes ‘Well, lad, if you’re not the Johnson group, then you’ll not be playing today.’ It just ate him up to be deceptive — he couldn’t do it.”

When the family watched film or television projects together about space, Neil was a stickler for the facts. If ever he noticed a mistake — perhaps the wrong video footage used to reference a certain mission — he’d get upset.

“That would just kind of ruin it for him — he’d just tune out,” Rick said. “I think the main thing that he would care about [with this movie] is that it be as historically and technically accurate as possible.”

So when it came to fact-checking the “First Man” script, the brothers wanted to be as specific as possible, even devising their own color-coding system for notes.

“Red was something that we cannot proceed with — if something was red, they needed to find some other angle on it,” explained Mark. “Yellow meant we had some concerns, but it wasn’t do-or-die. And if was green, it was like something you’d want to know, but it may not be that important. We just wanted an easy and convenient way to convey the depth of our conviction.”

Though “the red notes were by far in the minority,” Mark said, they tended to be about technical issues. In one version of the script, astronaut Mike Collins — who stayed in orbit around the moon while Neil and Buzz Aldrin tried to land on its surface — was communicating directly with the Lunar Module.

“He couldn’t have done that,” Rick said. “[We said] mess with that at your own peril. You will get crucified in the space community if you leave that in, and you don’t want that. So they took it out, and even a lot of the yellow ones got scuffed. Early on, there was a lot of profanity in the script [and] we said, ‘We know that’s common now, but back then, it wasn’t. If you’re trying to be authentic and you’re throwing in all these modern terms, you’re missing the boat.’”

The actual moon sequence is intimate in its focus, more interested in the astronaut’s private experience than the public spectacle. For his sons, “First Man” is also a reminder of what’s possible when people look beyond today’s petty partisanship.

“I hope that this movie reminds everyone — all the viewers, all the politicians, all the leaders in our country and around the world — that really great things can happen if you set a clear goal and get everyone working together,” Mark said.

For Chazelle — whose prior features, including the Oscar best picture nominated “Whiplash” and “La La Land,” were not based on real-life figures — having the brothers serve as their father’s conduit was invaluable.

“I remember when Rick came to set, we’d built the Armstrong house to a close-to-exact replica. And the first time he walked in he goes, ‘Very good, yeah. Do you want to know the things that are wrong?’” the director said with a laugh. “I was like, ‘This is so perfect. I loved it.’ It didn’t feel like people I didn’t know peering over my shoulder saying ‘You can’t do this, you can’t do that.’ It felt like any time I had a question, I had several people who wouldn’t guess — they would literally be able to say ‘I pressed that button, not that button,’ or ‘That didn’t happen in the kitchen.’ As much pressure as there was, there was also this opportunity to lean on people.”

Heading into the project, Chazelle admitted, he viewed Neil as somewhat of a mythological figure — “especially after his passing, thinking of him as a human being becomes harder and harder.” So he spent most of his time with the brothers asking them about their home life: What TV shows did Neil like watching? What games did he play with the kids? How would you know when you were in trouble, and what was he like when he was mad?

One of the most important things the Armstrong brothers shared with the production, though, went to Gosling. It was a thumb drive containing an oral history from 1968 featuring the voices of both Neil and Janet.

“I can’t say how helpful that was,” Gosling said. “I kept it with me all the time.”

“He even asked me to do a bunch of my dad’s lines the way I thought that he would do them,” Mark added. “I just felt that the more I would give, the more I would get back in return. And I think that happened.”

Gosling said he would have loved to have met Neil, had he been alive — but early in the process, so he could have “asked him if it was OK that I play him.”

“He would have been helpful, I think,” he said. “But you know, in some ways, this is a really special way to get to know someone — through their children and their family and their friends. I feel as though I did get to meet him, in some way.”

Follow me on Twitter @AmyKinLA