The first and only time I was on national television, I was giving a food tour to a travel TV show host around the San Gabriel Valley, proudly extolling the virtues of Cantonese roast duck, Shaanxi-style stewed lamb and vegetarian Chinese banquet food. I was 22, a recent college graduate who had carved out a niche writing about Chinese food in Los Angeles and terribly camera shy.

After the show ran, in a comment somewhere that has now been lost to the internet a stranger expressed incredulity about the way I spoke: how pronounced and distinct my Valley girl accent was, as if I were a character straight out of “Saturday Night Live’s” “The Californians.” The snark delighted and attracted other commenters like moths to a flame, who began to lampoon me for using upspeak, my liberal use of filler words and for my strong vocal fry. Their snide remarks left me scarlet with shame.

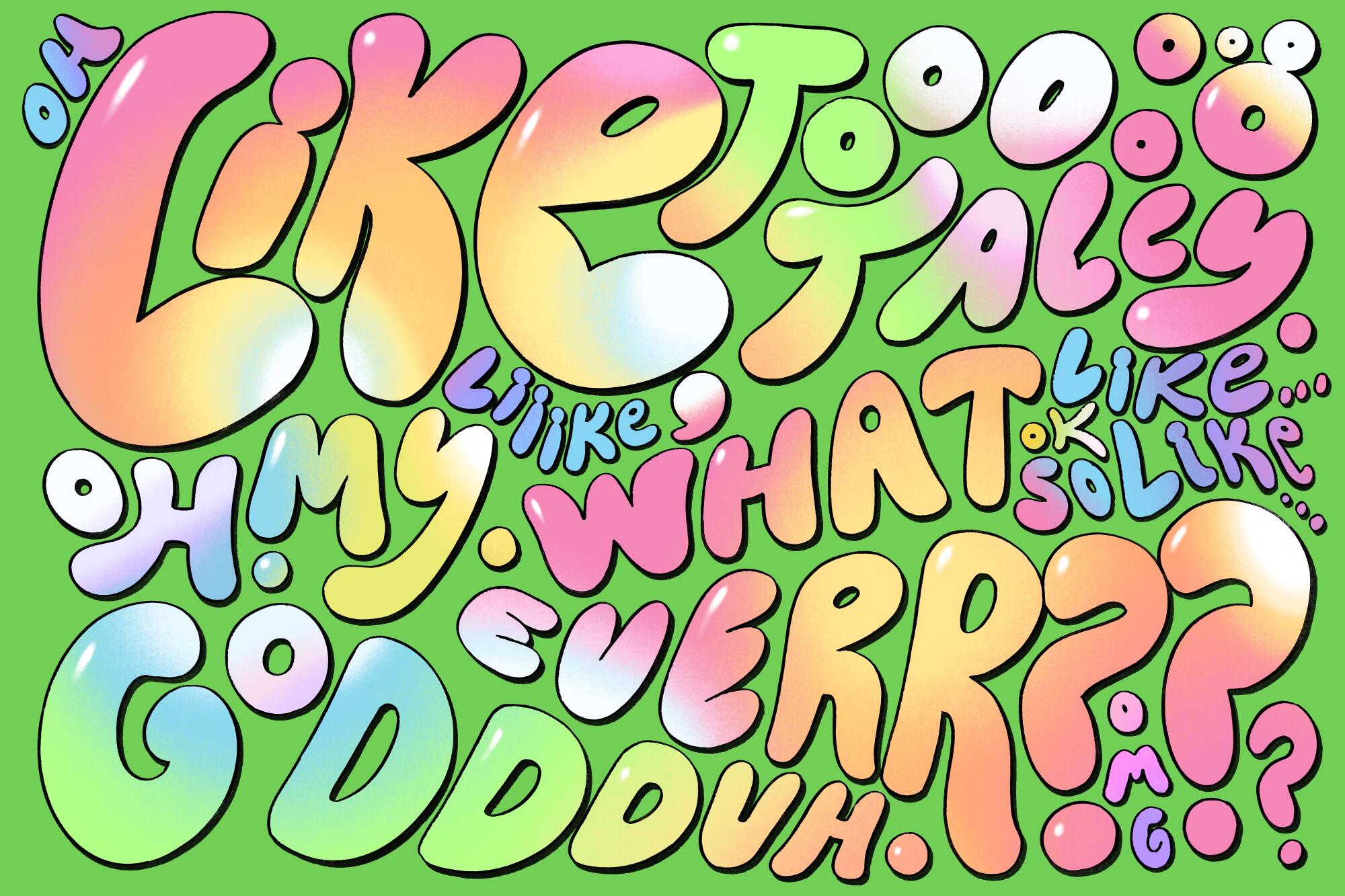

The origins of the Valley girl accent have long been an enigma, though it’s thought to have emerged as a phenomenon sometime in the ‘80s. It was first properly contextualized for the masses in 1982 through Frank Zappa’s satirical song “Valley Girl,” in which his 14-year-old daughter Moon Unit speaks in exaggerated “Valspeak,” mirroring the language she’d learned from other kids in the San Fernando Valley. “Like, my mother is, like, a total space cadet,” Moon says, as the chorus croons “Valley girl” on repeat between lines. “She, like, makes me do the dishes.”

To Zappa’s chagrin (two years later, he went on to call Valley girls “disgusting”), the hit single became a cultural touchstone. And ever since, the epithet has become synonymous with a stereotype of deeply annoying airheads from Southern California.

Yet in a globalized world where languages and accents are instantaneously broadcast and absorbed, how particular is the Valley girl accent to the actual San Fernando Valley or even to girls? Many of its signature features — the creaky voice, the upward inflection and the liberal usage of “like,” “whatever,” “totally” — can be found elsewhere in the world, pre-date the ‘80s and aren’t exclusive to women.

Yet somehow the combination of the above, transmitted through the voice box of a young adolescent woman, has become such a distinct trope that it’s been relentlessly skewered on TV shows and late night specials over the decades. In fact, the mockery and parody of the Valley girl accent has been described as “linguistic misogyny,” as one scholar put it, and the stigma is so strong that “[the] habitual use of creaky voice has been shown to undermine the success of women on the labor market.”

“People elsewhere do it and just don’t realize they’re doing it,” says Samara Bay, a celebrity speech coach who wrote a book about voice biases called “Permission to Speak.” “The difference is that people in Southern California have been told their whole lives that they do it.”

Cruel as they were, my critics weren’t wrong. In the truest sense of the term, I am an actual Valley girl. I am a child of the San Fernando Valley and spent the first 13 years of my life in Northridge, mostly affixed to the long axis of Reseda Boulevard. But as a daughter of Taiwanese immigrants, my early attempts at English were plagued with a heavy Chinese accent. There are childhood videos of me dancing to church songs, belting out the lyrics of Anna Warner’s Christian hymn “Jesus Loves Me.” I’d sing the refrain, “Jesus loves me this I know,” as “Geez-suz lav me thiss ay know.”

Eventually, I relearned how to speak in school and quickly picked up the traits of my peers, who, by virtue of where we lived, were all girls from the Valley. In a subconscious attempt to blend in, I lost my Chinese accent, replacing it with a crisp American English with distinct Californian characteristics.

I often and unironically used “dudes” as a gender-neutral term. “Like” wasn’t so much a filler word as it was a way for me to take a natural pause and think, though it would come bubbling out whenever I was particularly excited or nervous.

“We mirror our friends. We’re an amalgam of who we spend time with and who we idolize,” Bay says.

Back then, I never thought deeply about the way I spoke because I was surrounded by other Angelenos who sounded exactly the same. It was only when I had matriculated and moved to New York City as a journalism major that I began to become haunted by the sound of my own voice. For homework, we had to host, shoot and edit our own news reports. No matter how hard I tried, I could not mimic the velvety, robotic cadence of the reporters I saw on TV. The stereotypical broadcast voice — also sometimes known as the General American accent — with its crystal-clear enunciation, lowered pitch and steady pacing, is the antithesis of the Valley accent. Derived from how male anchors talked in the ‘70s and ‘80s, it is a standard that nearly all reporters at major networks are measured against, and an accent that is universally lauded and associated with intelligence and composure. “Certain accents around the entire world are considered better than others,” says Bay. “And this often comes down to colonialism, white supremacy and patriarchy.”

For me, speaking like a reporter felt contrived, like talking with socks in my mouth. I was terrible at it. What ended up coming out was a weird hybrid between reporter speak and Valley girl. In short, frighteningly unappealing.

“We can all walk into spaces calculating how do I sound the least like myself and more like a stereotypical standard of what powerful people should sound like. And that is an excellent short-term fix, because biases are real,” Bay says. “But what kind of world do we want to be living in? And might we reclaim aspects of our own voice and our own story about our voice?”

As much as I’ve become ashamed of it, my own voice, or rather, my true voice, is a Valley girl voice. And it’s followed me wherever I go. Today I live in Taiwan, where Mandarin Chinese is the lingua franca, and fixtures of the California accent have attached itself to my Chinese. When I try hard enough, I can smooth out its wrinkles and blend in. But like with my English, sometimes when my guard is down, elements of my childhood come out of the woodwork. Sometimes I find myself speaking Chinese in a squeaky, airy tone. Sometimes I even manage to throw in a couple of “likes.”

Although Valleyspeak is by no means exclusive to just young females, Bay explains why the demographic might be prone to it.

“It is incredibly useful as a coping mechanism,” she says. For instance, speaking with a vocal fry conveys a sense of nonchalance or detachment. “As a young woman — with all of the stereotypes around naivete and bubbly overenthusiasm — to seem detached is a great way of saying, ‘I’m good and I don’t need your approval,’” Bay says.

Upspeak, in which a sentence ends in what sounds like a question, is “a choice to not follow through the end of a thought energetically,” she adds. “It makes it sound like you’re declaring something, but you’re also taking it back.” By sounding noncommittal, the speaker is less likely to offend or come off as aggressive.

But if kids like me inadvertently took on the Valley girl accent as a defense tactic, many have consciously chosen to shed it in adulthood. I, for one, have managed to get rid of it completely in professional settings, such as when I’m recording a podcast or interviewing an important figure. I’ve since learned to slow down and deepen my voice. While my disguise isn’t foolproof, it has significantly altered the way people perceive me and I’m treated with more respect.

“I’ve done a really good job masking my Valley accent,” says Jessica Rassp, one of my friends from second grade who now lives in Maryland. “And when I turn it on, people are really surprised that it’s a real thing.”

Another childhood friend — Lily McKnight from middle school — admits that she also consciously hides her California voice now that she’s living out of state. “Since moving to Kentucky, I tend to tone it down as much as possible. It makes a fair number of people act weird,” she says.

McKnight has found that certain stereotypes attached to the Valley girl accent — the vapidness, superficiality and self-importance — are projected onto her when she uses the voice.

“People who identify me as being Californian react as if I’m judging them,” she says. And it’s a judgment that seems to be reserved specifically for females. McKnight notes that her husband is also from Southern California (albeit Irvine, not the San Fernando Valley), and even though he also has a distinct California accent, he’s never gotten the same type of disparaging feedback about his voice as she does.

It is unfortunate how an accent that I warmly associate with my childhood and with being at ease is so stigmatized by society at large. The only time I don’t actively try to hide my inner Valley girl is when I’m in the comfort of my own home with family and friends. Slipping into my native voice is soothing, like putting on sweatpants and a soft T-shirt after a long day in work attire and heels.

Bay, who is also from California, encourages me and others like me to lean into it in public. “It helps to see people that we admire speak in fresh ways,” she says. “If we all try to sound like the standard, and we all aim toward the generic, we’re just perpetuating the problems in our world.”

It seems silly to wish for a world where Valleyspeak is just as lauded as the newscaster accent. But who’s to say an accent associated with girls and women is less than any other? Maybe Bay has a point, and maybe one day we’ll actually, like, live in a world where girls from the Valley are allowed to be totally ourselves without judgment — breathy and totally, like, high-pitched, with sentences peppered with as many likes and totallys and whatevers and oh, my Gods, as we please.