The hotel charged by the hour, but the two young Cubans — dirty, hungry and dazed after being released from detention in the United States and pushed back into Mexico — had nowhere else to go.

The pair and some fellow Cubans detained with them pooled a few crumpled pesos that U.S. officials had returned in Ziploc bags along with notices to appear in court. Together, they crowded into an upstairs room with a single dirty mattress at the Hotel Sevilla.

They may wait six months to see a U.S. immigration judge just across the border in El Paso. And they face narrowing odds under President Trump that they’ll be allowed to stay in the United States.

Trump has returned to Cold War-era policies against Cuba, reversing his predecessor’s rapprochement with the government in Havana. But, in contrast with decades of bipartisan U.S. policy, administration officials not only no longer welcome Cubans to the United States, but are also pushing them out, forcing them back to Mexico and ramping up deportations to the island.

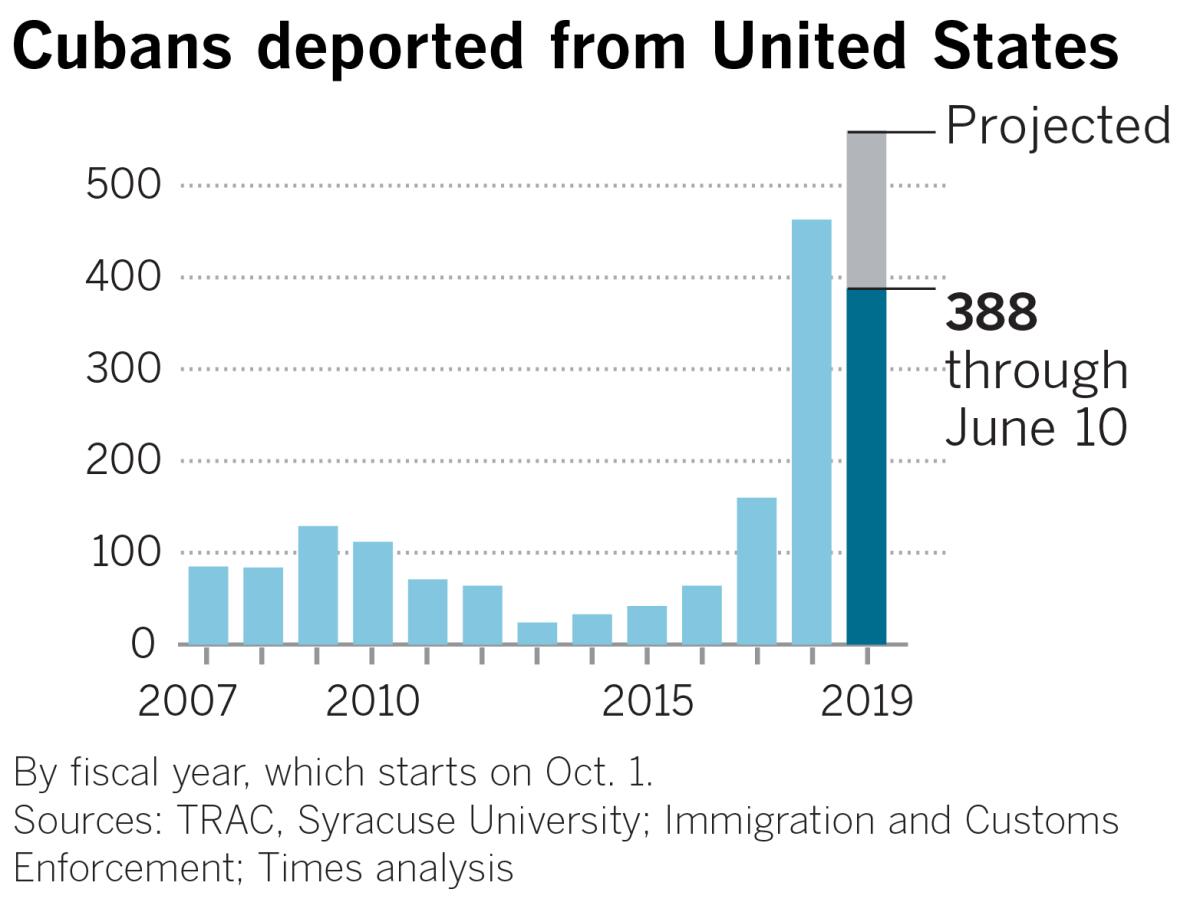

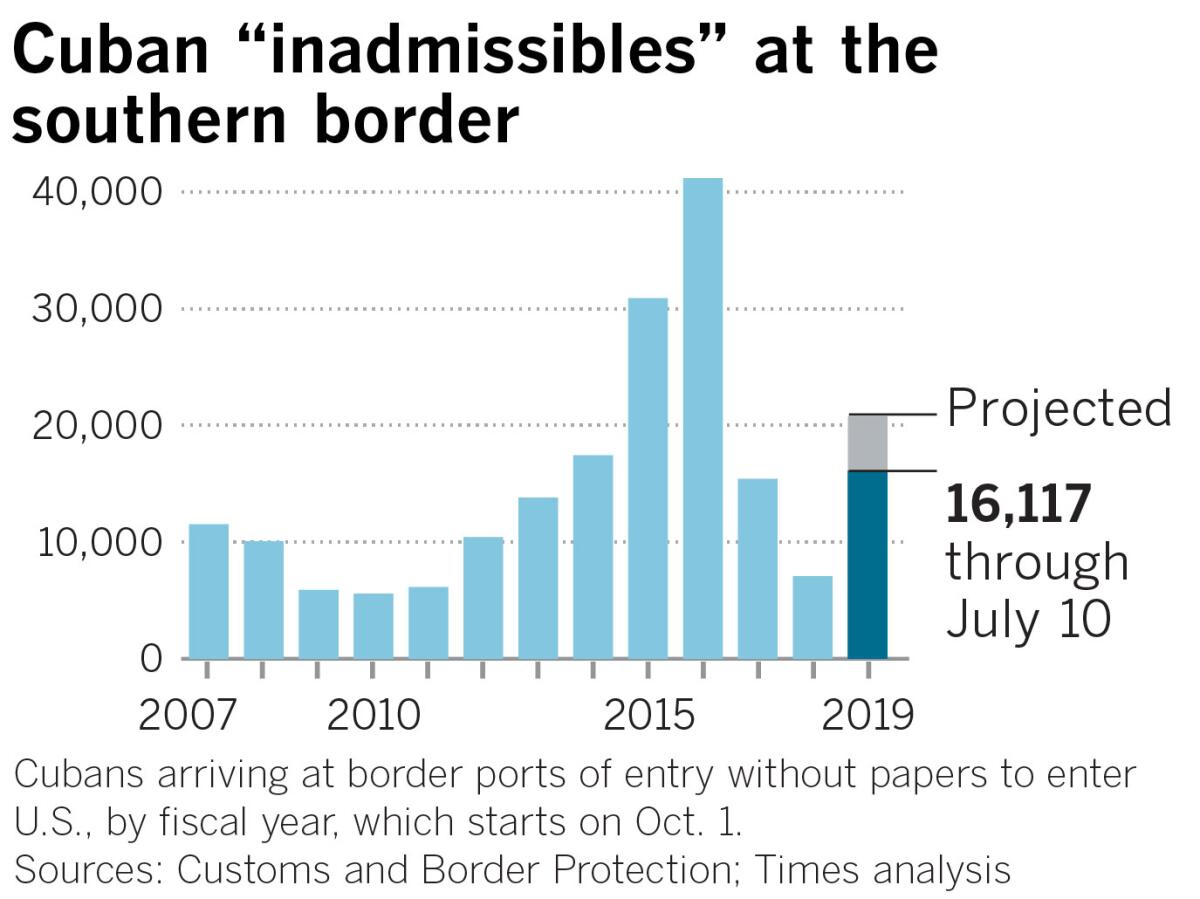

In 2016, the last year of the Obama administration, the U.S. deported 64 Cubans. Last year, the Trump administration deported 463. This year, officials are on pace to deport around 560. The number of Cubans showing up at the southern border without prior permission to enter, categorized as “inadmissibles” by Customs and Border Protection, has continued to mount, with more than 20,000 expected to seek entry this year.

The two young Cubans were among the first returned to Mexico last month under an expansion of a policy that had already required thousands of Central Americans to go back across the border while their asylum cases were proceeding in the United States. They insisted on remaining anonymous, fearful of harming their asylum cases, or putting themselves and their families in danger. Most Cuban asylum seekers have relatives in the U.S. and are prime targets for kidnapping and extortion in dangerous Mexican border cities like Juarez.

The two had arrived in Juarez on separate buses, the end of a journey begun with a plane flight to Nicaragua. At the advice of smugglers, both headed directly to the viaduct marking the U.S.-Mexico border and easily crossed the trickling Rio Grande, immediately turning themselves in and claiming asylum with U.S. Border Patrol agents waiting on the other side.

They thought they’d be allowed to stay.

“The coyote told us he’d get us into the U.S.,” said one, a 24-year-old from Bayamo, Cuba, “but it wasn’t correct.”

“It was all a lie,” interjected the other, a 19-year-old from Villa Clara who said his father was a U.S. citizen. U.S. officials overseeing their detention misled them, too, he added, telling them they’d be released in the U.S.

His father first applied to sponsor him to come to the United States eight years ago, he said. But now that he’s no longer a minor, “he says this is the only way.”

“They changed the laws as we were coming,” the first young man said heavily. “It was very bad luck for us.”

‘Holding the lid down on the pot’

Trump has quickly and quietly shifted U.S. policy toward Cuba beneath the feet of thousands of Cuban migrants, but the change began years before the two young men set out on their journey.

Starting in 1966, the Cuban Adjustment Act served as a virtual guarantee of legal residency and citizenship for Cubans who made it to the U.S. The law was part of the long-standing U.S. effort to undermine Fidel Castro’s Communist government by welcoming tens of thousands of Cubans who fled the island.

For decades, the U.S. followed a policy known as “wet foot, dry foot” under which Cubans caught at sea would be returned, but those who set foot on U.S. soil could stay. Under the 1966 law, after a year and a day, they could seek permanent residence.

But in January 2017, President Obama abruptly ended the“wet foot, dry foot” rule: Cubans would now be subject to deportation if they were detained at the border without a visa. Thousands of Cubans rushing to the U.S.-Mexico border in anticipation of the change were stranded, drawing criticism from Republicans.

But Obama had an unlikely supporter in ending “wet foot, dry foot” — Donald Trump, who entered the Oval Office a week later.

As president, Trump has reversed Obama’s moves to warm relations with Cuba. He has courted conservative Cuban Americans who largely opposed the thaw, particularly those in Florida, always an electoral battleground.

He has reinstated crippling sanctions that have worsened the island’s economic slide, banned cruises to Cuba, and allowed U.S. citizens who said their Cuban property was illegally confiscated decades ago to file lawsuits. He’s threatened the Cuban government over what he terms interference in Venezuela, on whose oil Cuba relies heavily. His national security adviser puts Cuba in a Western Hemisphere “troika of tyranny,” along with Venezuela and Nicaragua.

But he repeatedly says he stands with Cubans.

Yet Trump has not reinstated the wet foot, dry foot rule and, further, has ramped up removals of would-be Cuban immigrants.

The “explicit” goal of Trump’s Cuba policy is “making Cubans miserable enough to overthrow the government,” said William LeoGrande, a professor of government at American University. “It’s contributing directly to the increase in Cuban migration.

“We are intentionally holding the lid down on the pot so that people who are discontented can’t leave,” he said. “The hope is that the pot blows up.”

Trump’s hardline rhetoric against Cuba masks quieter cooperation with Havana, particularly on removing Cubans from the United States.

The State Department still labels Cuba “uncooperative” in taking back its citizens but has not levied penalties against the country as it has against other nations, according to the Homeland Security inspector general’s office.

“These actions are part of the ongoing normalization of relations between the governments of the United States and Cuba,” Customs and Border Protection says of Cuban removals, “and reflect a commitment to have a broader immigration policy in which we treat people from different countries consistently.”

With the primary legal avenue that once welcomed Cubans to the United States now effectively closed, many would-be migrants believe that claiming asylum at the border is the only way to get in. For the first time, Cubans rank among the top nationalities making claims of “credible fear” that they will be persecuted at home — the first step toward claiming asylum.

As of June, 882 Cubans had received asylum decisions in U.S. immigration courts this year, compared with 59 in 2016, according to Syracuse University’s TRAC database. The Cubans currently have a denial rate of about 50%, an improvement of their record under prior administrations — if they get that far.

So far, Trump has paid little political price for deporting Cubans or impeding them at the border.

Asked about the sharp increase in Cubans sent back under Trump, Sen. Marco Rubio (R-Fla.), a Foreign Relations Committee member and the child of Cuban exiles, called the removals “terrible.”

But with the volume of migration at the border today, he said, Cubans can’t get special treatment.

“It’s terrible it’s happening, because they’re going back to a country where there truly is repression,” Rubio said. But, he continued, “if you are arriving at the U.S. border and you don’t have a visa to enter the country — and there is a visa for Cubans that is backlogged because we don’t have enough people there [to process] — it’s hard to differentiate from one country to another.”

Sebastian Arcos, associate director of the Cuban Research Institute at Florida International University, said that “the reaction against this policy of returning Cubans to Mexico and to the island hasn’t reached a level significant enough that it could make a difference to the elections” in Florida, which is crucial to Trump’s chances.

Most longtime Cuban residents, he said, are “still happy with President Trump’s policies.”

‘He is closing the door’

At a shelter in the hills of Tijuana, Lazaro Guzman Castro and Adonis Barrera Sosa talked over each other, railing against political oppression in Cuba. Adonis said he was jailed for 36 hours and beaten after being arrested at a protest in Havana.

Adonis said Cuban police told him, “This is your last chance. We’re going to disappear you.”

The two friends, 32 and 31, raised like brothers, fled shortly after.

For all their bravado, they were open about their fears.

“We don’t go out at all,” Lazaro said. With their 20-day Mexican transit documents long ago expired, “they can deport us at any time to Cuba, and that means jail, torture.”

“Here, I’m very afraid,” he added. “We hear about robbery, murder, assault, kidnapping — especially for us, who have family in the U.S.”

They support Trump’s approach toward the Cuban government, even as his policy has forced them to wait almost two months in Tijuana on an unofficial list to claim U.S. asylum at the San Ysidro port of entry.

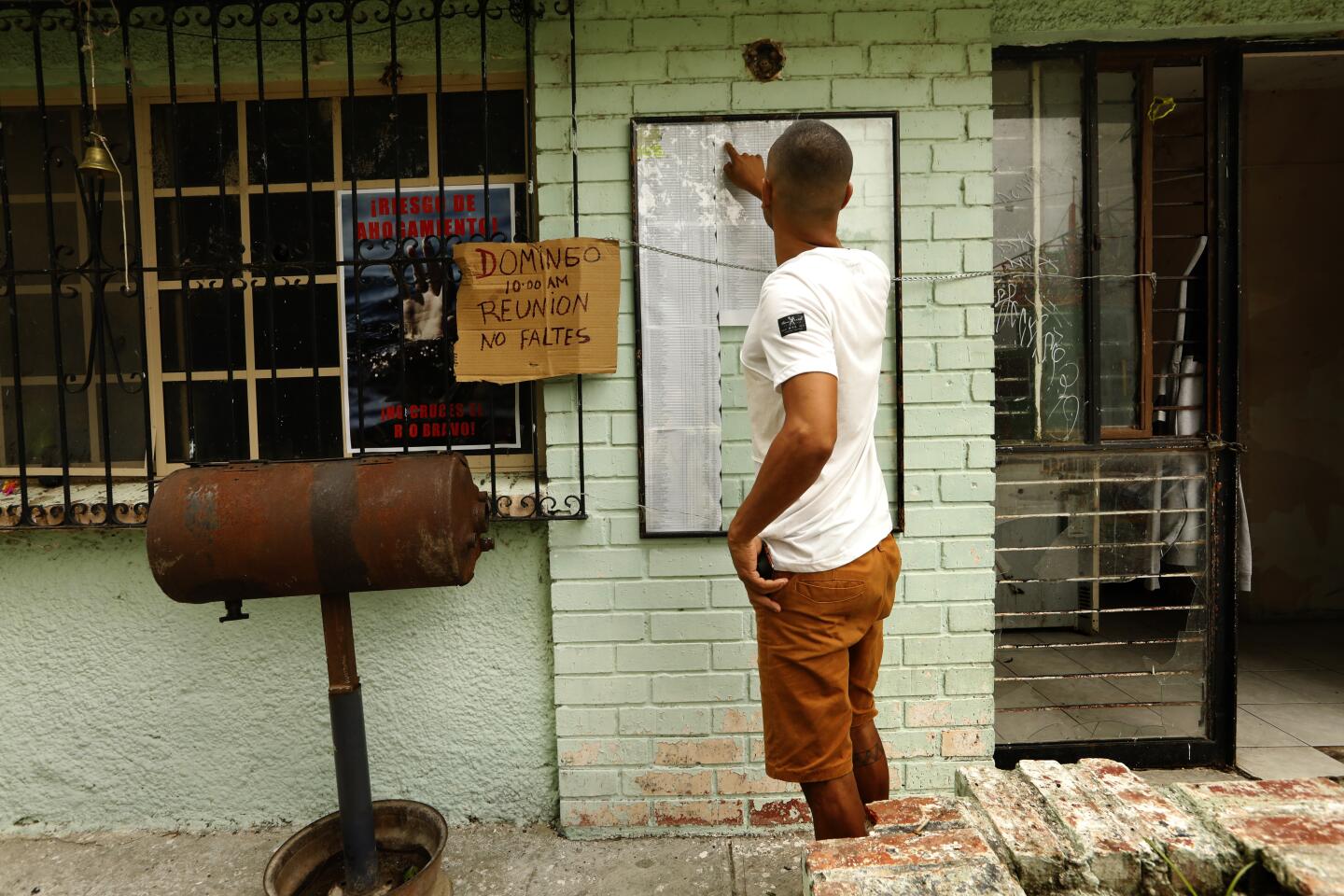

Lazaro hoped to join relatives in Albuquerque and Louisiana, and Adonis had family in Miami. Sharing No. 2943 on the list, the two likely have months before they have to think about splitting up.

“With one hand, he is putting pressure on the Cuban government,” Lazaro said of Trump. “But with the other hand, he is closing the door.”

The Cuban group in the Hotel Sevilla in Juarez appeared to have been the first Cubans to be sent back to Mexico under the administration policy of requiring asylum seekers to wait south of the border until their cases could be considered in an immigration court.

Shortly after, the administration expanded the policy border-wide, forcing Cubans and others who’d sought asylum at ports of entry from San Ysidro to Brownsville, Texas, to wait in Mexico. They join the more than 30,000 migrants already waiting in northern Mexico, either for a U.S. court appearance or to register their claims at ports of entry.

Melba Raquel Rivera, a 32-year-old from Varadero, Cuba, worked as a doctor for nearly a decade in Brazil as part of a Cuban government exchange program. Now, she works as a server at a Cuban restaurant in Juarez, where she has waited two months with her husband, holding No. 11654.

She’d heard U.S. officials were starting to return Cuban asylum seekers back to Juarez, and she was worried they’d begin sending them all the way back to Cuba.

Asked what she’d say to Trump if given the chance, she answered, “In Cuba, there is no freedom like you live.”

Times staff writer Molly Hennessy-Fiske in Matamoros contributed to this report.