Housing for homeless people? In Chatsworth?

Jason Brackett isn’t holding his breath.

“It’s not gonna happen on this side of town,” Brackett said one afternoon this month, pausing from pulling shopping carts down a sidewalk. “They don’t want us here.”

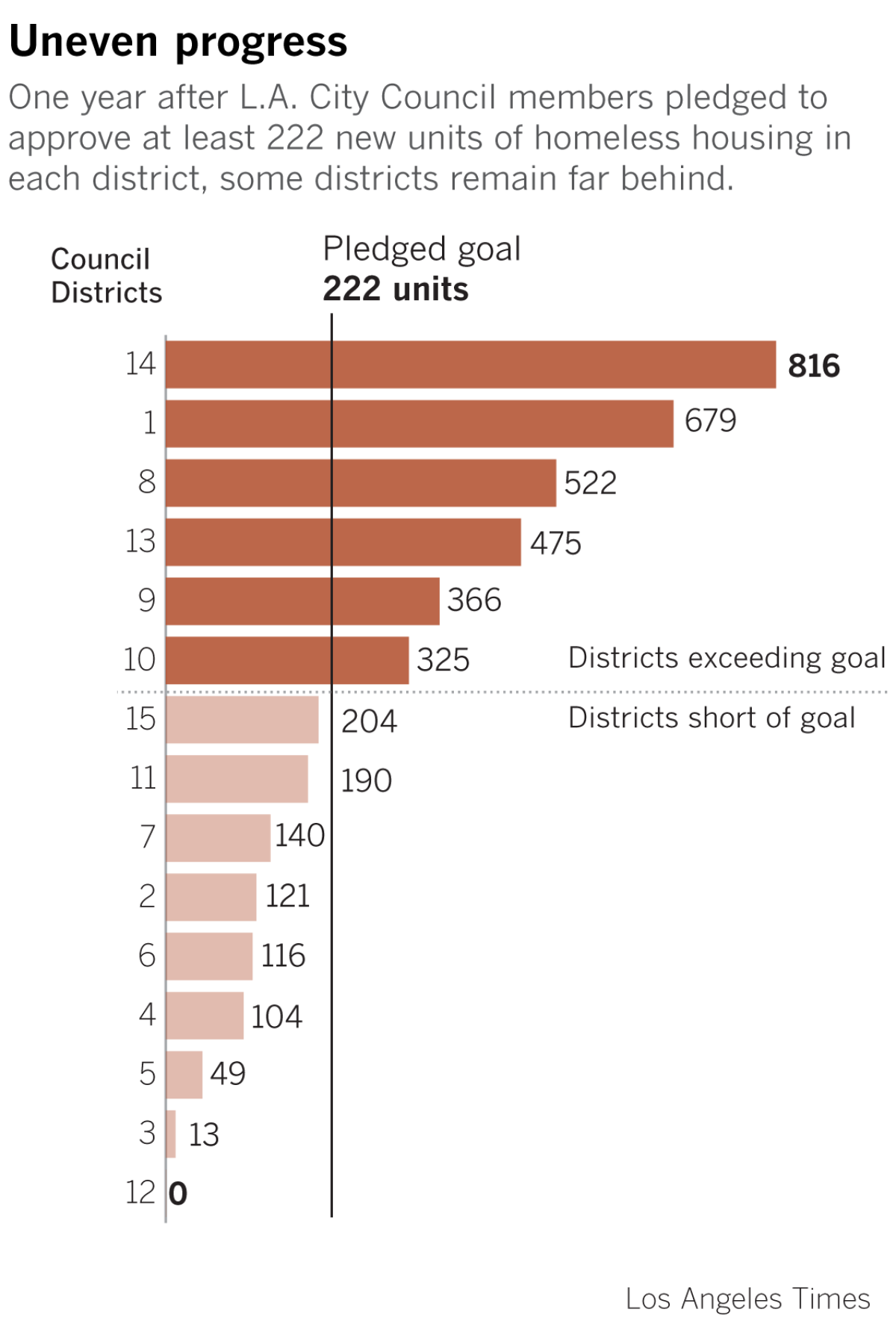

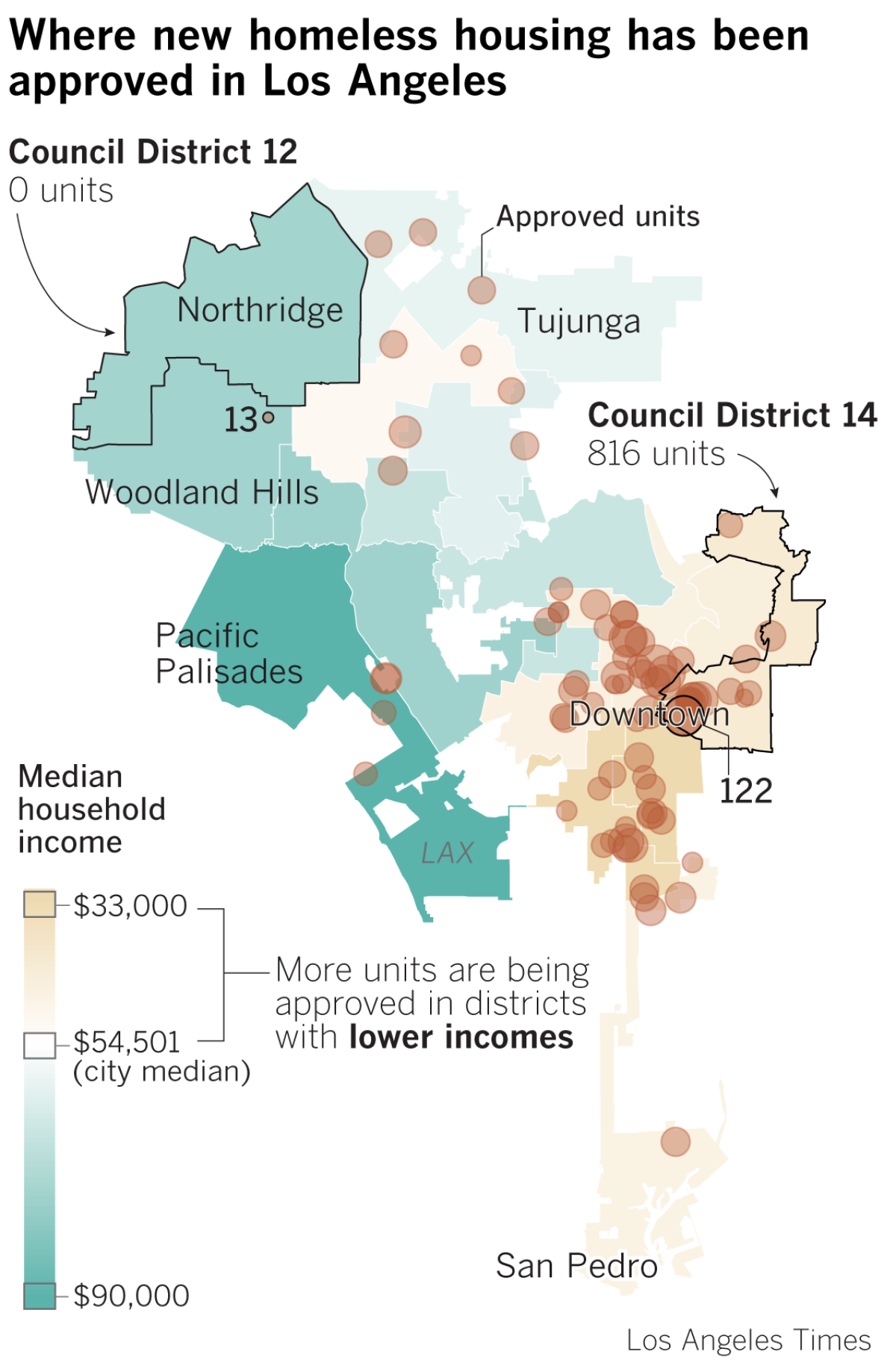

Despite the pledge that Los Angeles City Council members made one year ago Wednesday to support new housing with supportive services in each of their districts, zero units have been approved in this northwestern stretch of the San Fernando Valley, formerly represented by Councilman Mitchell Englander. And only 13 units have been approved in a neighboring district, represented by Bob Blumenfield.

The numbers are starkly different in the Westlake-to-Highland Park district represented by Councilman Gil Cedillo, where the city has already given the green light for more than 650 new units. And in Councilman Jose Huizar’s district, which covers much of downtown and Eastside neighborhoods including Boyle Heights and El Sereno, more than 800 new supportive housing units have been approved.

That uneven progress across L.A. has maintained the pattern that predated last year’s pledge. Housing for homeless people is still being disproportionately slated for lower-income areas — especially in and around downtown — and less so for affluent areas.

Just five of Los Angeles’ 15 city council districts account for nearly 70% of the homeless housing units that have been approved so far under Proposition HHH, the $1.2-billion bond measure approved by voters in 2016. Those districts cover parts of downtown and the central and eastern sections of the city, as well as South L.A.

Council members still have more than a year to make good on their pledge and meet their self-imposed goal of backing at least 222 supportive housing units in each district by July 1, 2020. But the ongoing pattern of where homeless housing is being built — and where it isn’t — has raised concerns inside and outside City Hall about perpetuating economic segregation and failing to address the need that exists across the city.

“There’s homeless people out there,” Cedillo said of Englander’s former district in the northwest San Fernando Valley, which includes Granada Hills, Porter Ranch and Chatsworth. “So it needs to be built out there.”

READ MORE: Across a diverse landscape, L.A’s hidden homeless live hard lives in fanciful ‘homes’ »

In the face of sluggish progress in some districts, politicians have blamed high land prices, a lack of interest from developers and other barriers. Colin Sweeney, former spokesman for Englander and now for interim appointee Greig Smith, said that after one project fell through, there were no other proposals for homeless housing in the area.

“We will duly consider any that come our way,” Sweeney said in an email.

When asked if the council office had taken any proactive steps to encourage such development, Sweeney said staff had done an assessment of surplus city properties in the district, but the few that existed were not zoned for the right kind of development. He declined a request to interview Smith, who took office in January.

District 5 Councilman Paul Koretz, who represents Bel-Air and other well-off parts of the Westside, has emphasized the high cost of land in his district, as well as stiff competition for available parcels. So far, only 49 new units of supportive housing have been approved — and Koretz said he is not “wildly optimistic” about hitting his 222-unit goal next year.

“People want to build market-rate housing and commercial projects in this district. Developers are grabbing whatever they can spot,” Koretz said. “It just hasn’t been easy.”

And Blumenfield, whose San Fernando Valley district stretches from Woodland Hills to Winnetka, lamented that “developers are not knocking on our door.”

Blumenfield said he has taken steps to encourage housing and services in his area: He enlisted the city to purchase a site in Reseda, which led to a project with 13 units for homeless residents. This year, he also asked city staff to assess whether some city-owned Reseda parking lots could be used for supportive housing.

“I don’t think the numbers are a fair representation of the work I’m doing,” Blumenfield said, arguing that the pledge did not obligate him personally to create units.

Homeless advocates say that building supportive housing all over Los Angeles will help people rebound in their own communities. Although the downtown area has the most homeless residents, including thousands on skid row, even the wealthiest and most suburban districts have hundreds of people who lack shelter, according to the Greater Los Angeles Homeless Count.

“It’s not only disheartening — it’s immoral” that Englander’s old district, does not have any HHH housing on the way, said Carlos Amador, a member of the Granada Hills South Neighborhood Council who is running for the City Council seat in June. “City leaders may not hear from community members who are homeless, but they exist in our district.”

In Chatsworth, roughly a dozen people bed down nightly in a makeshift camp of tarps and tents parallel to the Metrolink tracks — an area bounded by chain link fencing and a concrete wash that acts as a humble moat.Dogs bark gruffly from behind the wire.

Most people call it the Compound, said Kimberly Wetter, who has been homeless for a few years. But she prefers to call it the Gated Community.

“When you’re not homeless you think, ‘God, look at those people,’” Wetter said. “Then you get here.”

Living together feels safer than trying to survive alone, she said. Denizens of the camp watch out for strangers and warn one another when the police are near. As clouds gathered overhead one Friday afternoon, Dan Hacker — known to Wetter and the others at the camp as Butch — rolled up on his bicycle.

READ MORE: Many people work hard to avoid the homeless. These volunteers embrace them »

“Brought you something, Donna,” he called to another resident, pulling a package of Nutter Butter cookies from his pocket.

Hacker got into housing elsewhere in the San Fernando Valley in the past year, he said, but tries to visit the camp regularly. “It’s pretty nice having my own place,” he said. “But it’s a little lonely because I don’t know people in that area.”

Wetter and several others said they didn’t want to relocate to other parts of L.A. because they would feel lost. Brackett, the homeless man who was hauling his shopping carts down the sidewalk, said he knew Chatsworth like the back of his hand.

“Homeless people want to stay in the area they’re familiar with,” said Mel Tillekeratne, an organizer with the #SheDoes movement, which advocates to provide shelter for homeless women. “The retention rates [in housing] are only going to be high if we build housing where people are used to staying.”

Some residents remain skeptical of such efforts. Sean Dinse, an LAPD senior lead officer who is also running for the Englander’s old seat, agreed more supportive housing is needed in the district, but added that “housing is not going to solve this problem until we address the issues of mental illness and drug addiction.”

Neighbors “need to be able to trust that these supportive housing units are not going to turn into a nuisance,” Dinse said.

In December, Councilman Curren Price put forward a motion calling for the city to find new ways to encourage developers to build homeless housing in wealthier areas. Price said in a written statement to The Times that “the responsibility to fix the homeless crisis and the weight must be equally divided” across the council districts.

Under Prop. HHH, Los Angeles has started offering financial incentives to developers that build homeless housing on private property in neighborhoods with high land costs. Seven such projects have been proposed this fiscal year, including in Sherman Oaks and in the Fairfax neighborhood represented by Koretz.

Housing advocates also point out that despite the ongoing imbalance of where homeless housing is built, there has been progress. Before the pledge, 44% of the existing units of supportive housing were in Huizar’s downtown-to-Eagle Rock district, according to figures from the United Way of Greater Los Angeles. Out of the newly approved units, that number is 20%.

And new units are headed for areas that had little homeless housing in the past. In a district that runs along the Pacific Coast, Councilman Mike Bonin has backed nearly 200 units so far — a number that will quadruple the amount of homeless housing in that area, based on United Way figures.

PHOTOS: Homeless people at almost every L.A. landmark illustrates the depth of the problem »

Bonin’s district includes some of the costliest land in the city, but he has sidestepped that problem by championing projects on sites owned by the city and the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, winning praise from housing advocates. Some residents complain, however, that too many homeless projects are being slated for Venice rather than other parts of the district.

But city property is not a panacea: City analysts found that only four out of 428 “surplus” parcels could be used for housing or homeless services, since many were too small, already in use, impractical to build on,or had other issues. L.A. officials have since turned their focus to parking lots owned by the city, which has yielded some possible sites on the Westside and in Blumenfield’s Valley district.

Ben Winter, chief housing officer for Mayor Eric Garcetti, expressed hope that citywide initiatives meant to ease development — including incentives to build affordable housing along transit corridors — could help chip away, over time, at geographic inequity in housing for the poor.

But such segregation “has been decades in the making,” Winter said. “We won’t break down all those barriers at once.”

Twitter: @AlpertReyes