When Elizabeth Warren’s supporters tried to get her appointed head of a new federal consumer agency nearly a decade ago, they enlisted a surprising ally: Dr. Phil.

Yes, that Dr. Phil, the TV pop psychologist known for scolding cheating husbands, saving “beautiful daughters from … narcissistic” dads, and hawking diet pills that prompted a Federal Trade Commission probe and a $10.5-million legal settlement.

“I am such a fan” of Warren’s, Phil McGraw, Dr. Phil’s real name, wrote in 2010, urging President Obama to nominate the Harvard University bankruptcy law professor to lead the Consumer Financial Protection Agency, which she had helped create. He added, “We are so like-minded!”

Warren didn’t get the job in Washington, but the setback proved career-changing: It led her to run successfully for U.S. senator from Massachusetts in 2012, and now for the Democratic presidential nomination.

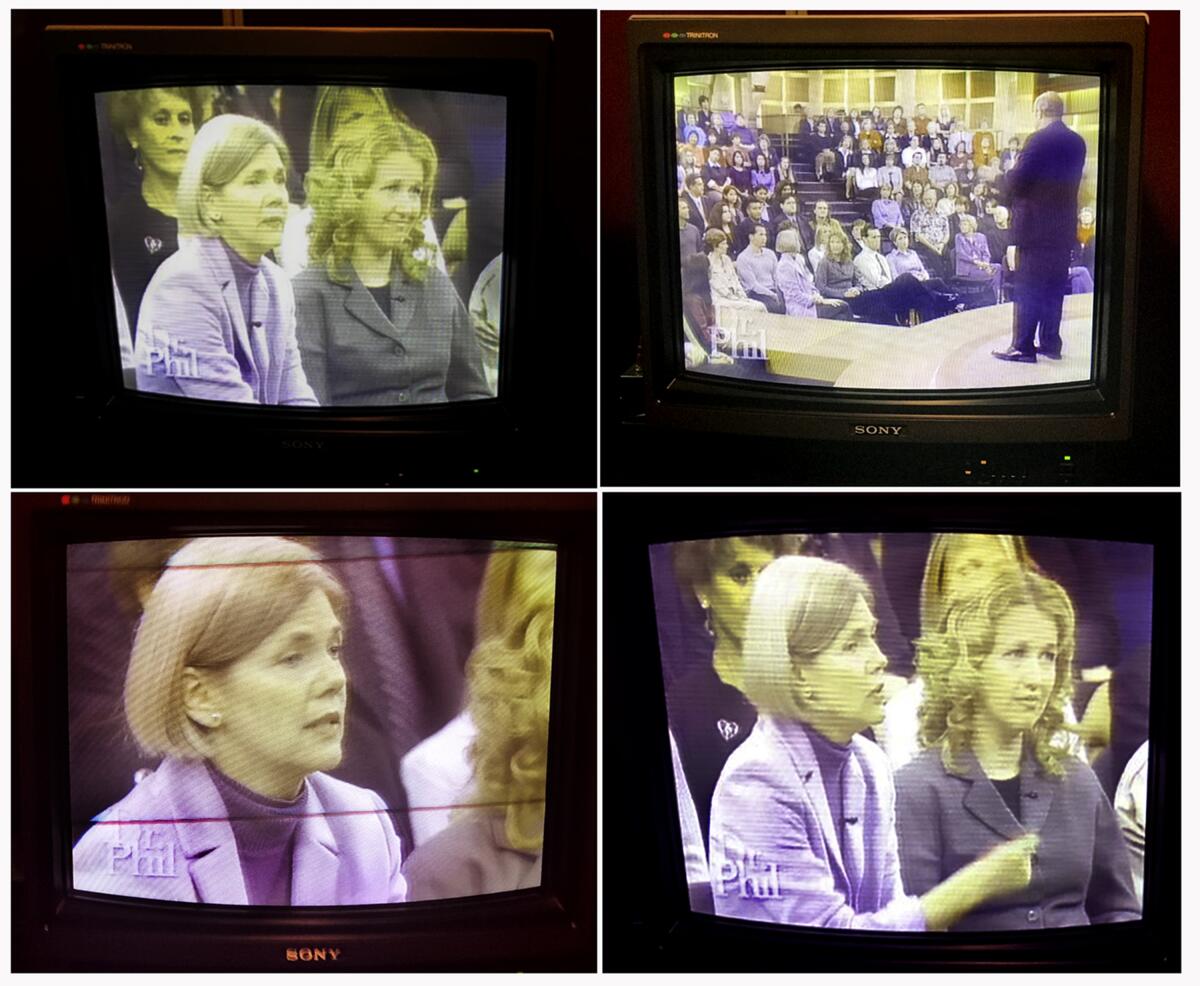

The interaction between the Ivy League academic and the host of a daytime TV talk show was crucial in another way. Between 2003 and 2005, Warren appeared three times on the “Dr. Phil” show, doling out personal finance advice to a live studio audience in Hollywood — and millions of Americans at home.

After the financial crisis in 2009, Warren expanded the role on late-night TV, appearing often on “The Daily Show,” which was popular with liberals. In one episode, host Jon Stewart was so enthusiastic about her plea for Wall Street reform that he said he wanted to make out with her.

A decade later, as Warren runs for president, that chapter in her life has taken on new relevance. She has risen steadily in the Democratic field partly because of her ease answering questions from voters in town halls — 128 such events so far — a format that echoes the give-and-take she learned on the talk shows.

Although critics find her style off-putting, Warren has shown an ability to connect with audiences, distilling her complex policy plans into simple concepts and slogans. Some of her rivals, by contrast, still sometimes use the stilted rhetoric of longtime legislators.

Warren’s early embrace of TV is also one of the rare qualities she shares with President Trump, who was a reality TV ratings king on “The Apprentice.” Both developed a public profile before seeking elected office.

The decision to go on “Dr. Phil” in 2003 wasn’t easy, according to Jamie Brickhouse, who trained Warren for media appearances after she wrote the best-selling “The Two-Income Trap: Why Middle-Class Mothers and Fathers Are Going Broke” with her daughter, Amelia Warren Tyagi. They wondered whether it was the right audience.

“Is it too tabloid, too down-market? Is it really going to sell any books? Is it the right avenue and is it right for her image?” recalled Brickhouse, then director of publicity for Basic Books.

In a telephone interview last week while she was campaigning in Los Angeles, Warren said she had little preparation for the show other than watching it and focusing on how she could ring “alarm bells” about problems facing families.

She laughed when asked whether she had hesitated because “Dr. Phil” wasn’t “Harvardy” enough.

“I didn’t know if I’d be any good at all, but I knew that if I didn’t try, I wouldn’t have a chance to reach Dr. Phil’s audience,” she said. “I was game to give it my all.”

Warren had spent years studying the causes of bankruptcy. She concluded that consumers were being unfairly blamed for excessive purchases when many were overextended because they had moved to areas with better schools.

“Dr. Phil” was not on the scheduled publicity tour, but McGraw was attracted to the final chapter, a “financial fire drill” offering practical advice, which was added at the suggestion of Warren’s editor, Jo Ann Miller.

McGraw “kind of positioned her as a financial guru,” Miller said. “We hadn’t really thought of her that way.”

“We thought of her as a person who was contributing to the national conversation on social issues,” Miller added.

Warren’s background — she grew up in Oklahoma in a family that sometimes struggled to pay the bills — proved as useful on TV as her Harvard pedigree.

“She had these kind of folksy sayings and images that kind of whittled down some of the wonky material,” Brickhouse said.

McGraw, also from Oklahoma, introduced her as an old friend on her first episode. In the interview last week, Warren said she had met McGraw years earlier in Dallas but had not maintained a friendship. McGraw declined to comment for this story.

In her 2014 memoir, Warren recalled the bright lights, the air conditioning backstage, and the people who insisted Amelia change her blouse before they sat in the front row.

The episode, titled “Going for Broke,” focused on three financially strapped couples. McGraw offered his usual tough love, calling one woman “spoiled” for demanding her husband pay for her designer jeans, Coach purse and other luxuries that ultimately drove them to declare personal bankruptcy.

“It is an addiction,” McGraw told her. “I’m not trying to beat you up. I’m trying to wake you up, girl.”

Warren sighed when McGraw asked her why a second mortgage was a bad idea.

“That’s playing roulette with your house,” she responded. “It’s just making the assumption that you’re going to take that house and you’re going to put it out there, and you’re going to take the spin and hope that nobody gets unemployed, nobody gets sick, nothing goes wrong.”

McGraw asked about financial institutions pushing second mortgages, prompting Warren to shake her head and wave her hands.

“Dr. Phil, that’s how they make money,” she said. “… So the whole idea out there is to tell you how smart you’d be, how clever you’d be, how safe you’d be, if only you’d take your house and put it on the roulette wheel.”

Warren also took a now-familiar swipe at the corporate world, noting that Kmart had filed for bankruptcy protection in 2002.

“Do you think that the CEO of Kmart sat around staying up nights worrying about that fact that all the big banks weren’t going to get paid? No, he did what was best for his shareholders. I think you need to do what’s best for your children and yourselves,” she said.

On another episode, Warren advised “Stacy” to get a job, despite Stacy’s insistence that her Mormon faith did not allow it.

Warren later credited McGraw for suggesting that she and her daughter write a follow-up book. “All Your Worth: The Ultimate Lifetime Money Plan” was marketed as a self-help bible, with step-by-step guides to “a Lifetime of Riches.”

Warren’s profile grew steadily as Washington politicians sought her advice. By 2009, she was leading an oversight panel appointed by Congress, grilling Wall Street executives whose banks were bailed out.

Producers on “The Daily Show,” which had scored ratings success by pounding Wall Street executives, took notice.

“We were reaching down further into the Washington bureaucracy than late-night talk shows typically do,” said Steve Bodow, a former executive producer on the show. “She seemed to be in exactly the right place to give us some insight into what was going on, and she was willing to talk.”

Warren later wrote that she vomited backstage before her first appearance. But Stewart put her at ease, nodding as she outlined the lack of accountability for big banks — and what she saw as a lack of concern for Americans who had lost their homes.

Stewart invited Warren back several times, giving her credibility with liberal activists.

“This is sort of a heyday of Jon’s bringing new ideas, new figures to the table,” said Charles Chamberlain, executive director for Democracy for America, a leading liberal group.

During a lengthy interview with Warren in January 2012, Stewart said he saw something different in her eyes when she described the role of government in society.

“I’m not idealizing you in that manner, but boy, that’s coming from somewhere,” he told her. “And I look forward to you getting in the Senate so they can suck that life out of you.”

Warren looked startled, and then she slumped back in her chair and laughed.