What do the Point Reyes lighthouse, French chemist Louis Pasteur and the Grateful Dead all have in common? Well, they’re all part of the origin story of how 420 methodically worked its way from a secret code to mainstream weed lingo.

In 1971, five San Rafael High School students were tired of Friday night football games and searching for parties. The five students called themselves the “Waldos,” referencing the wall they would sit on at their school. The wall, located in the main courtyard in front of the cafeteria, was the perfect spot for the Waldos to work on impressions of their fellow classmates and teachers.

They began occupying their time with adventures called “safaris,” after Steve Capper took them to what is now Silicon Valley in search of a holographic city that he read about in Rolling Stone. Safaris were a way for the Waldos to challenge one another to come up with something out of the box to do. Most took place in the Bay Area, but sometimes they traveled farther afield in California. There were two rules to safaris: They had to go somewhere new, and participants had to be stoned.

One day, the Waldos met at 4:20 p.m. for a “safari” and smoked all the Panama Red and Acapulco Gold — marijuana strains popular at the time for their potency and energizing qualities — they could get their hands on. The mission of this particular safari was to find an abandoned patch of weed. The meeting time stuck, as did the weed choice and their constant soundtrack of New Riders of the Purple Sage, Grateful Dead and Santana. Eventually, “420” became a secret code for the Waldos whenever they wanted to smoke.

A secret no more, 420 has become a representation of cannabis culture — love it or hate it — and a day and time that is observed by cannabis enthusiasts around the world. It was even a recent “Jeopardy!” clue.

The Waldos are Capper, Dave Reddix, Jeffrey Noel, Larry Schwartz and Mark Gravitch. They have thoroughly documented the term’s origins with postmarked letters, high school newspaper clippings and U.S. military records to corroborate their first 4:20 p.m. safari.

In 2002, Capper and Noel spoke to The Times about their role in coining the famous weed slang but wouldn’t reveal their names in print due to the stigma surrounding cannabis back then. Twenty years on and the Waldos are anonymous no more in The Times as cannabis legalization sweeps the country on a state level (it’s still illegal federally). Capper and Reddix, who have been open about discussing 420 in recent years, spoke by phone to explain what it was like to see the term take on a life of its own and their views on the future of weed. This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

What was the first 4:20 p.m. safari?

Capper: One day, the five of us were sitting on the wall and a buddy comes up and said his brother was in the Coast Guard, and a bunch of guys in the Coast Guard were growing some cannabis out on the Point Reyes peninsula. These guys thought their commanding officer was onto them and thought they were going to get busted. So, they decided to relinquish this pot-growing project. And they said [to my friend], “Hey, if you and your friends want to go pick it, here’s a map.”

So, [my friend] came to me and said, “Hey, here’s this map with free pot to pick.”

Reddix: It was a no-brainer. We had to go for it, right?

Capper: Jeff and Larry had football practice after school. We got out of school around 3 p.m. The football practice lasted about an hour, and just enough time for them to shower, get dressed and meet us. We met at a statue of Louis Pasteur, a chemist, on campus.

Reddix: We decided we’d meet there at 4:20 p.m. We got high in front of the statue, then we hopped in Steve’s ’66 [Chevy] Impala, and drove out in search of this patch, getting high all the way out there. And maybe that’s the reason why we didn’t find it.

Capper: We would remind each other in the hallways during the day, “420 Louis.”

Reddix: After that, we realized that this is a secret code we could use. We dropped the “Louis” part. We could use it in front of our parents, teachers, cops, friends, whatever, and they never knew what we were talking about.

How did you access weed at the time?

Reddix: Our brothers usually had it, or friends. And, at the beginning, the weed wasn’t as good as it is now. It was brown, dirt weed. You’d buy a bag of weed from somebody for $50. They call it a four- or five-finger bag. It wasn’t even weighed. You put your fingers up to see how deep it was, and it was usually filled with stems and seeds.

Capper: People are quick to forget this because of the environment now. Marijuana was certainly illegal. The consequences were very real. Smoking it, transporting it, selling it, buying it, it was all secretive and a lot of energy went into it. You could go to jail for 10 years for a joint. It was just ridiculous. But I think given that danger and getting through it together, there was like a brotherhood of cannabis outlaws.

When did you guys realize that 420 was bigger than an inside joke?

Reddix: We were using 420 for several years, and in 1975, when the Grateful Dead took a hiatus from touring, my brother was good friends with Phil Lesh (Grateful Dead’s bassist) and Phil asked Patrick (Reddix’s brother) if he would like to manage a couple of his bands.

He hired me to be a roadie and we were smoking weed backstage with Phil Lesh, David Crosby, Terry Haggerty, and I was using 420. It filtered through the backstage people and then that filtered into the Grateful Dead community. And that’s how it started climbing into the lexicon of the Dead community.

Steve, were you aware that 420 was being used by the Grateful Dead community?

Capper: Well, Waldo Mark, his father handled the real estate needs for the Grateful Dead. They needed places to rehearse, places to store their equipment. They had a whole organization to support, and they needed office space. They would buy homes in the Marin County hills. Mark’s dad would say, “Hey, they’re going out on tour. They need somebody to babysit their homes and take care of their pets.”

Mark’s dad would get us on the guest list, and we’d be backstage with them, and we’d be using the term. We’d pass them a joint and use the term “420.”

High Times Magazine wrote about 420 in 1991. How did that happen?

Capper: 420 celebrations were going on for years on a smaller level here in Marin County.

Reddix: And that became public knowledge because one of the editors at High Times, in 1991, was at a Grateful Dead concert, and he saw a flier that said, “Meet us to celebrate 420 on April 20th on the top of Mount Tamalpais on Bolinas Ridge.”

They did a little article on that. And then they started using 420 in their articles and referencing it.

How did you feel about the 420 celebrations?

Capper: [The celebrations] were kind of the ground zero of getting weed legalized. It was the beginning of [marijuana] activism and fighting back. The media started reporting on these gatherings and suddenly, April 20th became kind a forum in the media for discussing drug suppression and marijuana legalization.

Reddix: And [an early example] of marijuana legalization in California was SB 420.

Capper: So, in that respect, 420 certainly was a catalyst for legalization and reform.

You wrote a letter to High Times?

Reddix: We contacted Steven Hager of High Times back in 1998. He came out here and visited us. We took him around to all the places we liked to go. And then he went back and wrote that article, and then he went on television with ABC News, and he said, “I found the guys that started this.”

And by [2002], when the L.A. Times did an article about us, it was already semi-common knowledge. But still, a lot of people don’t know who started this.

Capper: I wrote a letter to him that said, “Hey, everybody thinks this 420 thing is a police code. That’s bulls—. It’s not the time that Jerry Garcia died. It’s not the number of chemical compounds in marijuana. And we have physical evidence, proof, going back to the 1970s.”

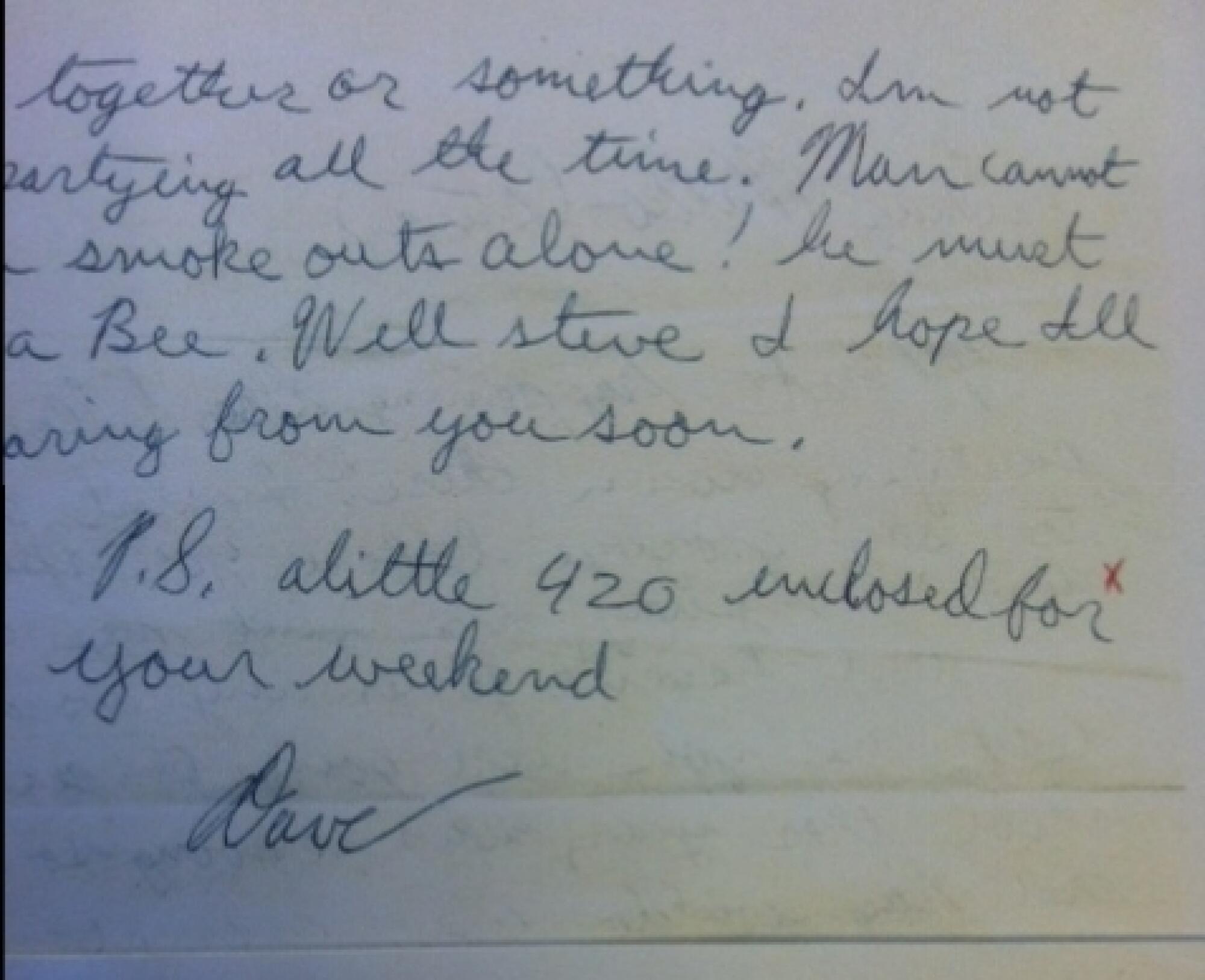

Reddix: We showed him these letters. One letter I wrote to Steve in the early ’70s, when he was at San Diego State. I told him about how I got this job with Phil Lesh’s band and I was getting high with David Crosby. I rolled up a joint and I smashed it down. I put it in the envelope and I said at the end of the letter, “A little 420 for your weekend.”

How did people try to poke holes in your story?

Capper: We had never met the Coast Guardsmen who grew the pot and people started to say there was no Coast Guardsmen.

We spent six years trying to find [my friend’s brother who gave him the map], trying to track him down. And after six years [in 2016], we found him. He was living homeless in the streets of San Jose. We tracked him down to what was about a three-mile radius. So, I hired this private detective to go in there and see if she could find him, and she got in.

They were having a Super Bowl in [Santa Clara that year], and they wanted to clear all the homeless people out of San Jose to make it look clean. I found a P.O. Box that he had, and we wrote to the P.O. Box and said, “Hey, we know you’re not going to have a place to stay. They want to kick all the homeless people out of the city. We can put you up in a hotel for a week if you’ll just get together with us and tell us your side of the story and what you remember.”

Reddix:We hooked up with [him] and he told us his story. He said at the time he was working on a ranch real close to the lighthouse.

Capper: He joined the Coast Guard Reserve.

Reddix: And that’s why he wanted to ditch that patch because he thought he’d get busted or kicked out of the reserves.

Capper: One of the main goals, because people were doubting our story, was to get his Coast Guard records, and he authorized [it]. So, we have 166 pages of U.S. Coast Guard records proving that he was in the Coast Guard in 1971 at that location.

Was there ever a time where you felt like you did not want to be associated with 420?

Reddix: In the very beginning, none of us wanted to. But then Steve and I came around and said, “Hey, this is ours, we should keep it. We should claim this.”

But the three other Waldos, they had kids in school, and they didn’t want to be stigmatized as marijuana parents. So, they stayed quiet until 2012.

What do you have planned for 420 this year?

Capper: There is a very famous rock artist. His name is Stanley Mouse. He did all those Fillmore posters in the ’60s. He did much of the Grateful Dead’s artwork. He’s friends with Larry, and he did an art piece that we’re going to release as an NFT on 4/20.

Reddix: When Larry asked [Mouse], “Would you do an NFT for us?” He said, “Well, OK, I could do that. But here’s how I feel about NFTs. It stands for ‘nothing f—ing there.’”

Capper: Also, we have been busy trying to connect with filmmakers that would share the vision of our story, extensive backstory and its sociological effects.

Do you still smoke?

Reddix: We all partake, but we don’t do it daily.

Do the Waldos get together on 420?

Reddix: We usually get together and sometimes we’ll go to the Lagunitas Brewery (Lagunitas-Heineken releases a Waldos special ale for 4/20). But last year, during the pandemic, we couldn’t see each other. Waldo, Larry and I virtually smoked a joint together on FaceTime.

How do you feel about the cannabis culture in California right now?

Reddix: Well, I think we have to embrace it, but it’s not the same as it used to be. It doesn’t have the same vibe as when we were doing it, but there’s still a vibe of community and comradeship.

Capper: Usually, there’s pretty good spirit in the dispensaries. But to the extent that it migrates to just a retail store and marketing and money transactions, I’d rather have the vibe go into one of those places that have the recharge feeling of the ’70s. Goodwill, friendliness, kindness, tolerance. To have that kind of spirit surround the industry, I hope that continues.

How often do you guys get together?

Reddix: We talk to each other every day or every other day, and we still go on safaris every once in awhile.

Capper: We’ve been at each other’s weddings, our kids’ graduations, bat mitzvahs. It’s certainly a family. All that huge amount of backstory just shows 420 is just the tip of the iceberg of the whole Waldo story and culture.