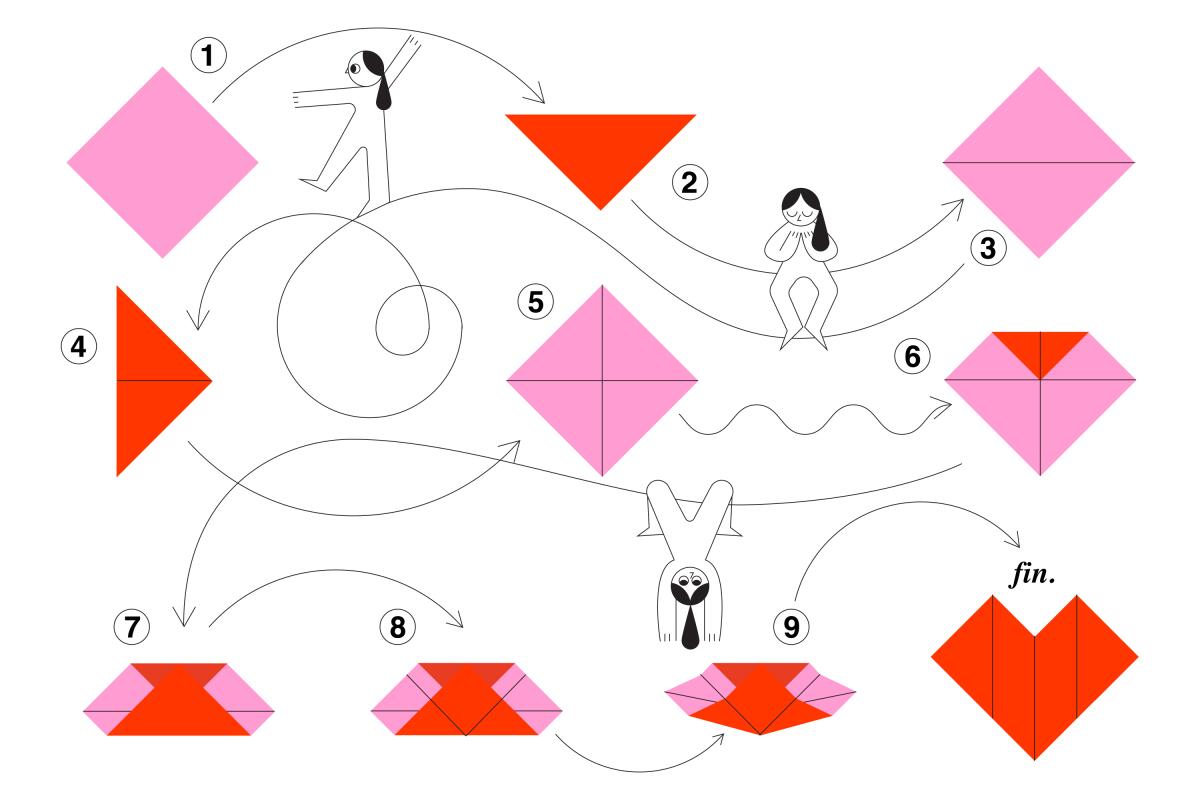

Every day I set aside time to transform sheets of paper into colorful origami hearts. My fingers fold the paper into a series of squares and triangles that are reliant on patience and precision. I repeat the same folds on each side, finding beauty in the symmetry and satisfaction in the creation.

I started this daily origami practice a few months ago when I was in a rut. For more than 20 years, I’ve been in recovery from anorexia nervosa — a disorder I developed after my mother died from metastatic breast cancer when I was 11. I was in treatment as an adolescent and am now far better than I ever imagined I’d be. But my recovery remains an imperfect work in progress.

Sometimes I slip up. I’ll turn toward or away from food when I’m feeling overwhelmed, or I’ll spend too much time critiquing my reflection. During recent appointments with my nutritionist, Dr. Michelle Albers, I found myself fixating on my slips. She recommended that I shift my focus — by celebrating small victories and creating something in recognition of them.

“Behavior change of any kind is a nonlinear process with many steps forward and back,” said Albers, a registered dietitian in Florida who has spent the last 35 years working exclusively with people who struggle with disordered eating and eating disorders. “Clients struggling with eating disorders can have an unrealistic expectation, often of a ‘perfect’ path to recovery, and find that when they can celebrate small steps along the way, they can sometimes feel encouraged to continue along the path. It’s a reason to continue celebrating victories even as recovery progresses.”

With this in mind, I started making an origami heart every time I made a notably healthy choice. I take photos of each one and send them to my nutritionist, with mininarratives about the choices that inspired them. There are origami hearts for the days when I ate an afternoon snack rather than telling myself to wait until dinner; for the times when I ate hearty portions that honored my hunger; and for the recent night when I let my husband know I was craving cake and asked if he would get me a slice from the grocery store. (He gladly did, returning with slices of Italian cream cake and tiramisu cake, which we ate while snuggled up on the couch together.)

The hearts harken back to an earlier time, when I was hospitalized for anorexia at Boston Children’s Hospital 25 years ago. I was admitted, in part, because my own heart was weak from starvation, beating far slower than it should have for a 13-year-old. One of the other patients taught me how to do origami, wowing me with her ability to fold paper into cranes and turtles and hearts. I soon learned how to make them myself and found that the art of folding paper quieted my mind in ways that nothing else could.

When I folded I felt freer, and my mental load lightened. I could focus on my moving hands instead of my racing, disordered thoughts. Doing origami also made me feel closer to my mother, who had cross-stitched her way through cancer, fashioning tiny X-shaped stitches into beautifully embroidered landscapes. While facing my own trauma in the hospital, I finally understood why cross-stitching mattered so much to my mother during all of her cancer ward stays.

“When you go through a really traumatic event, you lose a sense of agency and control over your life,” said Girija Kaimal, an associate professor in the Creative Arts Therapies program at Drexel University and president of the American Art Therapy Assn. “If you have an artistic practice that you can turn to that helps you regain confidence in yourself and in your ability to manage and function, it can be a tremendous resource and coping tool.” Kaimal researches the physiological and psychological benefits of creative self-expression, and has found that engaging in artistic practices can significantly reduce levels of cortisol, the so-called stress hormone.

As I deepened my origami practice in the hospital and during subsequent stays, the hearts became aspirational. Maybe I will love myself someday, I’d think while folding them. Maybe one day I’ll get better.

The years passed and I did get better. But as I moved further along in my recovery, I moved farther away from origami. I did reengage with it at some points during my adulthood, like at my wedding, where there were place cards adorned with miniature origami hearts and 1,000 paper cranes on display in tall cylindrical vases. But after getting married and having children, origami felt like one more thing to add to an already exhaustive to-do list. Like so many of our artistic endeavors, mine peaked in childhood and then plateaued.

One way to reengage our creativity is to think of artmaking as a playground of sorts. “When you see art as a space to play, it becomes a space where you can make mistakes with no consequences,” said Nadia Paredes, a Los Angeles-based art therapist who has encouraged some of her clients to literally draw outside the lines. “By the time you make a mistake in real life, you have a bigger sense of strength and a bigger sense of confidence that you can handle whatever happens.”

When you engage in a daily creative practice, the process of creation is often more important than the product itself. “What matters most is how you feel while creating it, and what you get out of the creative process,” Paredes said, noting that it’s important to recognize when there are changes in both the process and the finished product.

When I compare my recent origami hearts to the ones I made in the hospital, I can see that they’re now bigger, with folds that are less exact. I notice these little imperfections, remembering that I used to crumple up the origami paper into a ball if I made something that turned out less than perfect. Back then, every flaw felt like a failure. Now, I can appreciate the uneven spaces between folds and laugh at the lopsidedness of my hearts’ rounded tops.

I share the hearts with my two young children and keep the rest for myself, storing them in mason jars on my desk. I like admiring them during the workday in quiet recognition of all that they stand for. They’re reminders that progress is possible, and that slips don’t have to turn into uncontrollable slides. Each handmade heart is a celebration — of tiny triumphs in my recovery and of choices guided not by my disorder but by hard-won self-love.