“I attend Catholic service every Sunday,” my date said and perked up proudly across the table.

My instinct said to leave after the appetizer — I was raised in communist Bulgaria by atheists who taught me to associate religion with dullness of mind. I don’t have friends who believe in God or go to church. But having lived in California for a decade, I’d been working on “opening up to the universe” and being less judgmental. So I stayed.

The fact that Andrew had thick black hair, wore a cool gray blazer with a fringe trim and had manners that were a perfect balance between Continental blue-bloodedness and rugged American utility helped. But what really got me were his eyes, blue and intense, emotional and honest, like he knew some deep truth. Jedi eyes, a friend later said.

Andrew was a Texan. He had the grounded dignity of a man who knew where his roots were and knew where he was going. He mispronounced “charcuterie” and was not embarrassed when the server corrected him. He smiled openly instead.

The long string of depressive, foreign, sometimes stateless, atheist intellectuals I had dated in my 20s and 30s paraded in my mind’s eye: an exiled Kurdish journalist; a theoretical physicist from Cuba; a South African composer; a Pakistani American economics professor fluent in French.

Like these men, I had no childhood home in America, no buried forefathers linking me to the land, no young cousins or nephews tying me to its future. I didn’t go to anniversary parties, family reunions, Christmas dinners or Easter brunches. My mother thought Mother’s Day only served to further enslave women and promote the patriarchy, so we didn’t celebrate that either. These men I mentioned and I shared sexual chemistry, aesthetic sensibilities and an understanding of the world as an ultimately dark place full of suffering. We hurt each other because we were hurt.

I think I saw in Andrew a happy rootedness I deeply craved.

For our next date, I invited him to Irish actress Lisa Dwan’s performance of three short Beckett plays staged in complete darkness. He didn’t seem interested in the “blinding exposition” of “existence as a wound” (as it was described in The Times) but came anyway. He wanted to make out in the dark. It felt refreshing.

On our third date, he came home with me. The sex was carnal and connected. We liked each other. We’d fall in love easily.

In the morning, Andrew woke early. It was Sunday. “I’ll go to early church service and come back for breakfast,” he said.

As I lay in the crumpled, sweaty sheets, I texted friends, “My date left my bed to go to church. Church! What do I do? I actually like him.” Confused emoji.

Friends’ texts buzzed back. My neighbor Ryan said, “He’s Christian? You know what to do — dump him.” My brother accused me of being a moral relativist. My closest friend was in denial: “How religious can he really be if he hangs with you?” My mother later said if we liked each other, perhaps he’d come around to see the “right way.”

At breakfast, Andrew was happy. He ordered a Sloppy Joe and told me that a young Latino man, a former gang member, had spoken at the service. He’d survived six gunshots, two in the head. His survival was a miracle, part of God’s larger plan. I cringed, though I liked that Andrew had compassion for this man.

Perhaps I was envious that Andrew felt safe in the belief that human suffering had a larger purpose, that a kind and smart God had figured it out, and we just had to trust. Andrew had someone to catch him if he fell. I didn’t. Never had.

When I was 11, the Bulgarian communist government that was supposed to last forever collapsed, leaving us with no teachers, schoolbooks, jobs, heating or food. Three years later, when we moved to America, my family crumbled with my parents’ divorce. When I was in my early 20s, my father took his own life. I was now 36. In the upcoming decades, my friends would start getting ill and dying, and at some point I, too, would crumble. There was no larger plan.

One day I opened Google News. The state of Texas was not allowing transgender school students to use the bathrooms they wanted. Andrew said, “The whole transgender thing … I’m against it. It’s like: Choose a side.”

I believed a person was randomly born into a country, a family, a gender. Why did one have to be bound for life by an accident of geography or biology?

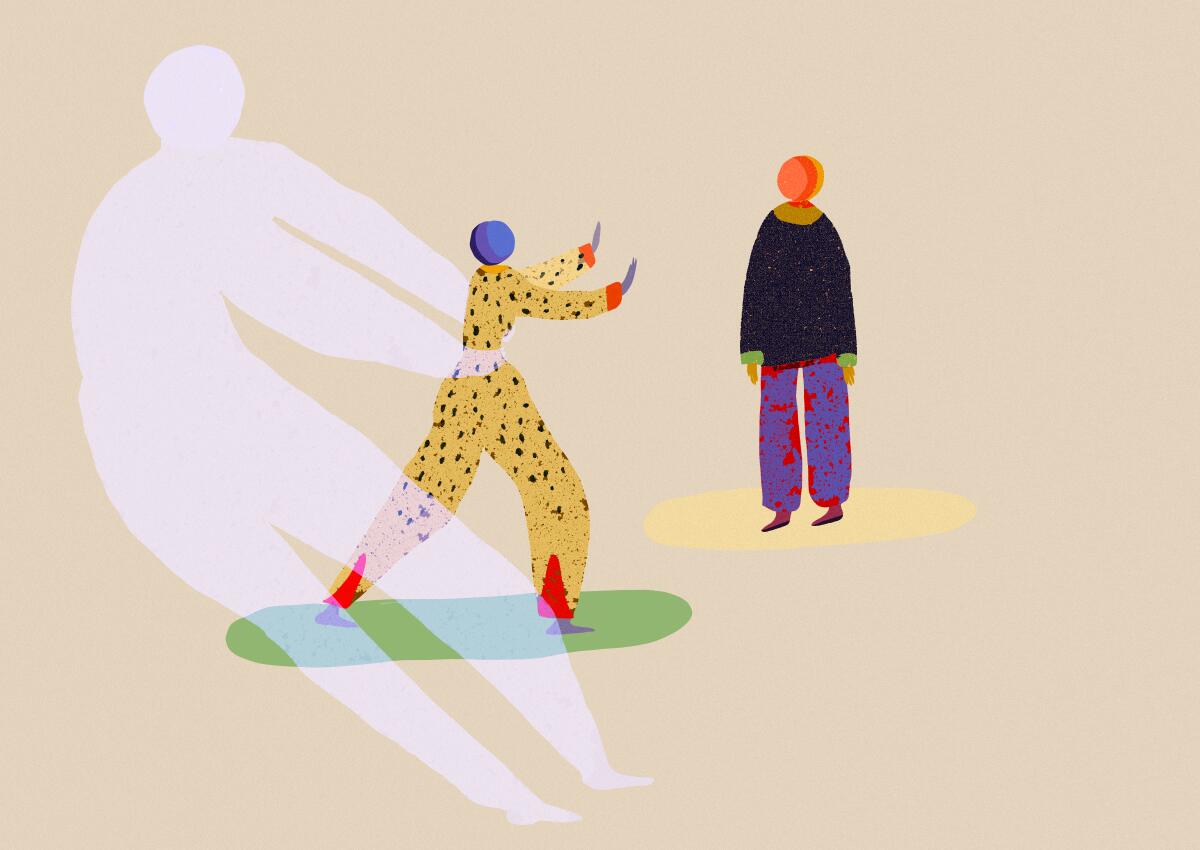

I realized that the rift between Andrew’s and my worldviews was so deep, there was no common ground, just two tectonic plates moving in opposite directions. One could not build a home on this.

Contrary to what my new-age yoga teachers said — to go with the flow, to open to the universe — the things I had chosen to ignore (my judgment, if you will) did matter because they communicated an inner ideology, a hierarchy of values that permeated and even guided what one thought and did. A person interested in Beckett would likely not believe transgender surgeries were wrong. In trying to “open up to the universe,” I had betrayed my own intuition.

After I broke up with him, Andrew persevered. He left concert tickets and books on my porch. I asked him to stop. He said exchanging books was “nice.” In hopes of running into me and persuading me to be together, he started crashing my friends’ happy hours. In his own way, he was perhaps fighting for me. But he wasn’t hearing me. It seemed he had a bigger plan for me.

The author is a Bulgarian-born writer of short stories and a lecturer of Russian language and literature. She lives in Los Angeles. She is currently finishing her first novel.

L.A. Affairs chronicles the search for romantic love in all its glorious expressions in the L.A. area, and we want to hear your true story. We pay $300 for a published essay. Email [email protected]. You can find submission guidelines here. You can find past columns here.