On a fall day in 2019, one of Hollywood’s top lawyers drove through the foothills of the Santa Monica Mountains to see Hunter Biden.

Biden’s life had reached a critical point. His father was in a crowded primary field for the Democratic presidential nomination. The younger Biden had decamped to a poolside midcentury rental that looked out over the San Fernando Valley — newly sober, newly married and climbing out of the wreckage of years of crack and alcohol addiction with a daily ritual of painting.

After briefly meeting at a recent fundraiser, Kevin Morris arrived to view Biden’s art. They retreated to Biden’s kitchen table, where Morris posed a question: How are you doing?

The reply stretched over several hours.

Morris retrieved a legal pad from his car and took notes as Biden opened up. His life — already marred by the deaths decades ago of his mother and baby sister — had by then seemed an unstoppable calamity, starting with the more recent death of his brother, Beau, the depths of his crack addiction, the mounting alimony, the unpaid and unfiled taxes, the Arkansas woman who claimed he fathered her child, the escalating political attacks and more.

Together they made a list of things in Biden’s life that had to be tackled.

It was the beginning of an unlikely relationship that would confound and fascinate both Hollywood and Washington.

Morris had built one of the entertainment industry’s most successful law firms and inked groundbreaking deals for the creators of “South Park” and A-list stars including Matthew McConaughey.

Biden was viewed by many as the troubled black sheep of an American political family who was becoming a scandal-ridden piñata for the right wing and a messy liability for his father.

Four years have passed since that meeting — a period that saw the revelation of Biden’s personal data, supposedly from an abandoned laptop; his father’s defeat of Donald Trump; indictments in California and Delaware; and now, an impeachment inquiry against the president. Biden has been molded into a caricature of corruption but also a figure of pity, recast with each new allegation and indictment. In short, radioactive.

In that time, Morris and Biden have spoken nearly every day.

Morris has assumed several roles in Biden’s life, foremost as his lawyer, but also his friend, confidant and bankroller. He has lent millions of dollars to Biden to cover his tax debts, housing and legal fees. He has also helped build a community of people around Biden who support him in his sobriety. And he welcomed, even enveloped, Biden with his own family, particularly Morris’ brothers and late mother.

In standing by Biden, Morris himself has become a figure of speculation, scrutiny and, in some quarters, suspicion.

Who is he? How has he become one of Biden’s closest confidants?

And for those who crossed paths with Morris over his decades in Hollywood, many wonder: Why?

Friends offer a few clues. Morris struggled through his own addiction, and since turning away from alcohol more than 20 years ago, he has helped others. Despite their divergent paths, the men shared things in common.

Both hailed from tightknit Irish Catholic families in towns southwest of Philadelphia. Although Morris is about seven years older than Biden, they attended high schools whose sports teams competed against each other. Both were lawyers living in Los Angeles who in middle age had turned to creating art.

Morris was a risk taker and rule breaker in Hollywood, and it made him incredibly rich — the very same qualities, say his close friends, that characterize Morris’ relationship with Biden. “Certainly it’s not careful, but he’s a gunslinger. This is how he rolls,” said one.

Some Hollywood associates have distanced themselves from Morris. Others worry about the toll his connection to Biden is taking on his life and finances.

Morris declined to comment for this article. But there is one person who accepts Morris’ new commitment without question.

“I don’t know where I would be if not for Kevin,” Hunter Biden told The Times. “And I don’t mean just because he has loaned me money to survive this onslaught, I mean because he has given me back my dignity. He’s been a brother to me.”

“What was in it for Kevin?” asked Biden, who lives in Malibu. “I think that you don’t truly understand or know Kevin if that’s your question.”

A few weeks ago, Morris sat in the back seat of a black SUV squired by Secret Service agents as it wended its way through Washington traffic.

When the vehicle pulled up outside the Capitol, out stepped Hunter Biden, trailed by Abbe Lowell, his defense attorney, and Morris, who held a phone to film what would happen next.

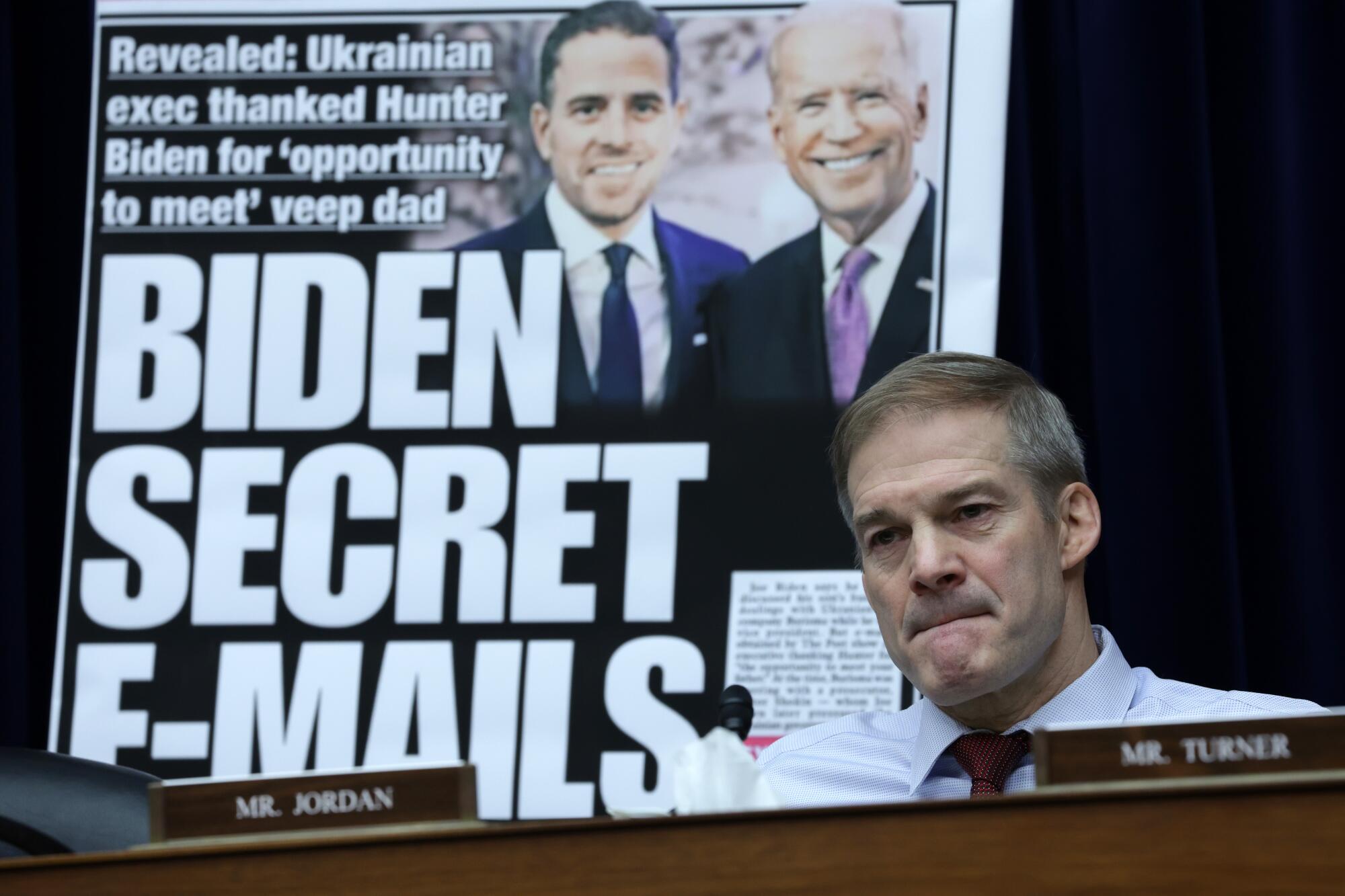

For months, Republican lawmakers had fashioned Biden’s follies into a political voodoo doll in their quest to pin an impeachment inquiry onto his father, the president. In the fall, they had issued a subpoena demanding that he appear for questioning.

At the appointed hour on Dec. 13, Biden was nowhere near the hearing room.

Instead, he marched through a scrum of reporters to a lectern as cameras snapped his unexpected arrival.

Biden was taking charge of the show — if only briefly.

With the gleaming dome of the Capitol in the background, Biden declared that he would comply with the subpoena — so long as he could testify in public.

“Republicans do not want an open process where Americans can see their tactics, expose their baseless inquiry or hear what I have to say,” Biden said, catalyzing the day’s top news story. “What are they afraid of?”

Biden had previously said relatively little while his father’s opponents hurled attack after attack.

Now he went on the offensive. While the words were Biden’s, it was Morris whose resources had allowed the president’s son to stand there.

The Hollywood deal maker, who had flown in from L.A., was just out of frame, next to a Secret Service agent and nodding as Biden spoke.

The extent of Morris’ counsel to the president’s son is clear only to a few insiders.

One of them is Lowell, a high-profile D.C. lawyer who has had a front-row seat to decades of Washington scandals as a representative for the likes of John Edwards, Charles Keating, Jared Kushner and Gary Condit.

Even he says Morris’ role is something new for him.

“I have never in any of my representations of any other client — other than someone who is an immediate family member of one of my clients — known anyone who is like Kevin,” Lowell said, citing “the intensity of his friendship and his commitment to” Biden.

Lowell had been aware of Morris only by reputation. As he has worked with Morris and Biden on a cornucopia of legal issues, Lowell said he witnessed firsthand “his passion.”

Lowell has observed that Morris feels the ups and downs of the cases involving Biden and said that sometimes, “it seems to me it impacts Kevin more than it impacts Hunter — impacts emotionally.”

A throng of cameras recorded Biden’s words and beamed them out to the world. His news conference led cable news.

Nestled among the news reporters was another camera crew. But it had a different mission.

For years, it had been following Biden and filming his travails for a documentary that Morris has backed.

The strategy isn’t a novel one. A documentary would allow Biden the person — a father and husband — to be presented without a middleman: painting, selling his art, raising his son and navigating everyday life as a sober adult with ongoing criminal investigations and in the crosshairs of Trump and his supporters.

With a documentary, Biden, and to some extent Morris, could possibly get the last word.

The Morris family had lived around Philadelphia for more than a century by the time Kevin was born in 1963.

His mother and father, a secretary and a lab supervisor, raised him and two other sons in Media and nearby towns in Delaware County, an area of Pennsylvania made famous in HBO’s gritty drama “Mare of Easttown.”

“He couldn’t wait to go — he always knew he was bigger than the town we grew up in,” said youngest brother Brian Morris.

Morris’ late father, Patrick, was an alcoholic and could be volatile at home, particularly toward his eldest son. “My dad was mean to Kevin,” said brother Dennis Morris. Kevin found refuge in the local youth center, where he played basketball.

It was an upbringing far different from the son of a Delaware senator.

For a time, Morris shared a bed with his brother in their relatives’ home, and the family went on food stamps when their father was laid off. To save their mother from embarrassment, Morris would do the grocery shopping.

Morris worked as a bartender while studying at Cornell University and harbored dreams of becoming an artist and writer.

As graduation loomed, Morris was uncertain about his career and recognized the grim prospects for a life in the arts. So he opted for New York University’s law school, “needing something that was concrete, that had some possibilities,” as Glenn Altschuler, a Cornell professor and author who has remained close to Morris since his undergraduate studies, put it.

Morris got a job in the civil litigation department at the Los Angeles firm Lillick, McHose & Charles, where he had interned the previous summer, in part to be near his girlfriend, Gaby Morgerman, who later became an agent at the William Morris Agency.

His position entailed handling routine litigation defense for corporate clients. He was miserable and drank heavily, according to friends. Morris lasted two years at the firm.

What kept him interested in the profession was partly the salary — multiples of what his parents made during their fourth decade in the workforce.

With his love of film, television, writing and music, Morris decided to pursue a career as an entertainment lawyer.

But none of the top entertainment law firms in Los Angeles wanted him. After bouncing around for six months, Morris got part-time work at one firm but soon decided to strike out on his own.

In exchange for desk space for his new solo outfit, Morris handled bank financing and production matters for the executive team behind the Motion Picture Corp. of America (MPCA). Known for cult classics like “The Purple People Eater,” MPCA would later produce the blockbuster “Dumb and Dumber.”

Morris hit up young, up-and-coming actors and independent filmmakers cold. He focused on developing direct relationships, making a case for himself, offering to handle their contracts — sometimes for free.

Steve Pink, the screenwriter and director who later wrote “High Fidelity,” among other films, recalled meeting Morris on the balcony at screenwriter Buck Henry’s house. Pink’s career had barely taken off, but Morris told him he needed an attorney to protect his creative interests.

“For him to recognize me as someone who could have success was heartening,” Pink said.

After seeing an early cut of the 1993 film “Dazed and Confused,” Morris made it his mission to meet a then-23-year-old Matthew McConaughey.

When they met at a restaurant in Venice they instantly hit it off, drinking and talking almost daily.

Morris urged McConaughey to push for the lead in “A Time to Kill,” after he was asked to read for a supporting role. Author John Grisham saw his screen test and approved.

Not long after, Morris made what would become his other seminal connection, meeting a pair of little-known filmmakers named Trey Parker and Matt Stone.

It was at the Sundance Film Festival in 1994. Morris went to see their out-of-competition film playing at the Yarrow hotel. It was a musical about Alferd Packer, an American prospector arrested for cannibalism in 1883.

Morris was wowed watching Parker singing astride a horse, and afterward he found Stone. They got drunk, and so began one of the most lucrative troikas in television history.

A year after meeting at Sundance, Parker and Stone showed Morris a crudely rendered, foul-mouthed animated short, “The Spirit of Christmas,” now famously known as “Jesus vs. Santa.” It was a prototype for what became the worldwide phenomenon “South Park.”

Mainstream networks, including Fox, passed on the series, finding the content too offensive and controversial, but Morris negotiated its home on the then-fledgling Comedy Central.

“South Park” premiered in 1997 and pulled in nearly 1 million viewers, unheard of for basic cable at the time. It put Comedy Central on the map.

“He was their biggest cheerleader,” a former network executive said of Morris. “In the early days, when they were young and sowing their oats, their actions might elicit eye rolls from us, but never from Kevin.”

By then, Morris, still in his early 30s, teamed up with Michael Barnes, a friend and former partner at a law firm where Morris briefly worked, to open Barnes & Morris.

The new firm set up shop in the former headquarters of Louise’s Trattoria in Santa Monica, sharing an office building with a yoga spa.

Shortly after opening, Morris recruited Kevin Yorn, a 30-year-old L.A. County deputy district attorney who was prosecuting murders in the Hardcore Gang Unit.

The hire was typical of Morris, who picked staff from nontraditional backgrounds, including those who had gone through the juvenile detention system.

Four months after the firm opened, Morris would need Yorn’s prosecutorial experience after he was charged with two counts of driving under the influence.

To resolve the case, Morris appeared at a West L.A. courthouse in the spring of 1996 with Yorn, his subordinate, as his defense attorney. Morris pleaded no contest to one of the charges and the other was dismissed, according to court records.

The judge sentenced Morris to probation and ordered him to complete three months of alcohol counseling.

The ordeal, about two years before his first child was born, appears to have put him on an alcohol-free path. An attorney for Morris declined to discuss the incident.

Friends told The Times that Morris prefers not to talk about his sobriety but that he takes it seriously. (Although he gave up alcohol, associates have said that Morris indulges in pot smoking and considers himself “California sober.”)

As a managing partner, Morris eschewed many traditional law firm operations and borrowed aspects from how talent agencies were run. Law school graduates initially joined as “assistants.” For 18 months, they immersed themselves in the industry, covering the studios, reporting on them at weekly meetings. The firm didn’t keep timesheets.

Barnes & Morris was small, unorthodox and soon very successful. Billings grew by 40% year over year, according to those familiar with the firm’s finances. Within 10 years they took over an entire floor at 2000 Avenue of the Stars, later the home of CAA.

The firm’s client roster grew as well. In addition to McConaughey, Parker and Stone, the practice would go on to represent John Cusack and his writing partners, along with Scarlett Johansson, Ellen DeGeneres, Jim Carrey, Will Ferrell, the Wayans brothers, the Duffer brothers, Jason Sudeikis and Chris Rock.

The firm took a chance on Anthony Zuiker, a tram driver at a Las Vegas hotel who had an idea to write a show about crime-scene forensics. That idea became “CSI,” the blockbuster television franchise.

Morris formed deep friendships with his clients, becoming their mentor, rabbi and consigliere. He read scripts and also counseled them on roles, real estate and rehab.

“Talent can leave you whenever they want, there’s no handcuffs,” said Stuart Liner, an attorney and friend who has known Morris for years. “For many years he wasn’t great about retainer agreements. He just trusted people.”

It was Morris whom McConaughey called at 2:30 a.m. from Texas in 1999, when the actor was arrested after he was found naked and playing the bongos.

Along the way, Morris earned a reputation as a fierce negotiator, with a Jekyll-and-Hyde quality that, although effective, often stunned allies and foes alike.

“You never knew which Kevin you were going to get,” said one former network executive who found himself across the table from Morris on numerous occasions. “Kevin can be tricky. He was volatile at times where he would lose it, literally. At times he worked himself into a lather.”

Douglas Mark, a partner at the firm from 2000 to 2007, said Morris could be charming and charismatic but was also a “bully,” who was frequently “screaming at people, blowing his stack.”

He recalled that Morris singled him out with taunts because the recording industry’s upheaval at the time left the firm’s music division lagging far behind other segments.

The situation between the two came to a head in 2005 during the firm’s off-site retreat at Yellowstone Lake in Wyoming. Morris wanted everyone to paddle in canoes to an island during inclement weather. Mark did not, and when he declined, he claimed that Morris ridiculed him, calling him names. “I decided I’d had it,” he recalled.

Mark said he paddled over to Morris’ canoe. Using his paddle, Mark tried to “whack [Morris] and knock him out of the boat.”

An attorney for Morris declined to comment about Mark’s account.

The firm’s growth was propelled by innovative thinking and a series of landmark deals often initiated by Morris.

“The business is dividing between those who see trouble everywhere and those who see opportunity everywhere. We see opportunity everywhere,” he once told Variety.

Back in 2007, a time when digital rights didn’t rank as much of a consideration in deal making, Morris secured a precedent-setting ad-sharing deal with Viacom. It landed Stone and Parker a 50-50 split with Comedy Central on all digital and non-TV revenue generated from “South Park.”

Stone later praised Morris for making it happen, telling Bloomberg News, “It’s almost so ancient to think about someone in the room saying, ‘If it’s online, you can have that.’ Can you imagine that? That really happened.”

It was around this time that Morris visited Parker at home and the latter surprised his lawyer by performing the song “Turn It Off,” followed by “Hello.”

They were the opening notes to what would become the blasphemously funny, Tony Award-winning Broadway blockbuster “The Book of Mormon,” created with Stone and the writer and composer Robert Lopez.

It was Morris who raised the money for the production, including plowing $1 million of his own funds into the show.

Liner, the friend and attorney, recalled Morris asking him to invest $100,000. After Liner politely declined to participate, Morris went silent, and, uncharacteristically, stopped returning his phone calls.

“After two weeks went by, I realized it wasn’t about the money. This was about loyalty. So I called him and said I’m in for $100,000. He said, ‘Great.’ And that thing has been a juggernaut.”

To date, “The Book of Mormon” has grossed over $1 billion worldwide, making it one of the most successful musicals of all time.

With his many triumphs, Morris’ fortune ballooned along with his lifestyle. He added a portfolio of art and real estate, including the $10-million Malibu compound previously owned by Olivia Newton-John, which he purchased with Morgerman, whom he married in 1991. (The couple are currently separated but remain close friends.)

Still, the rejection he experienced at the start of his career stayed with him. The brushoffs metastasized into a grudge against the established entertainment lawyers that Morris has called “arrogant” and “lazy.”

Morris seemed to cultivate the image of the outsider. He frequently appeared rumpled and unshaven. In a business characterized by the prim elegance of Hollywood attorneys like the late Bert Fields, Morris seemed more at ease wearing T-shirts and long hair.

“His persona was this swirl of hard-charging lawyer, activist and surfer dude,” said an individual who attended several meetings with him over the years.

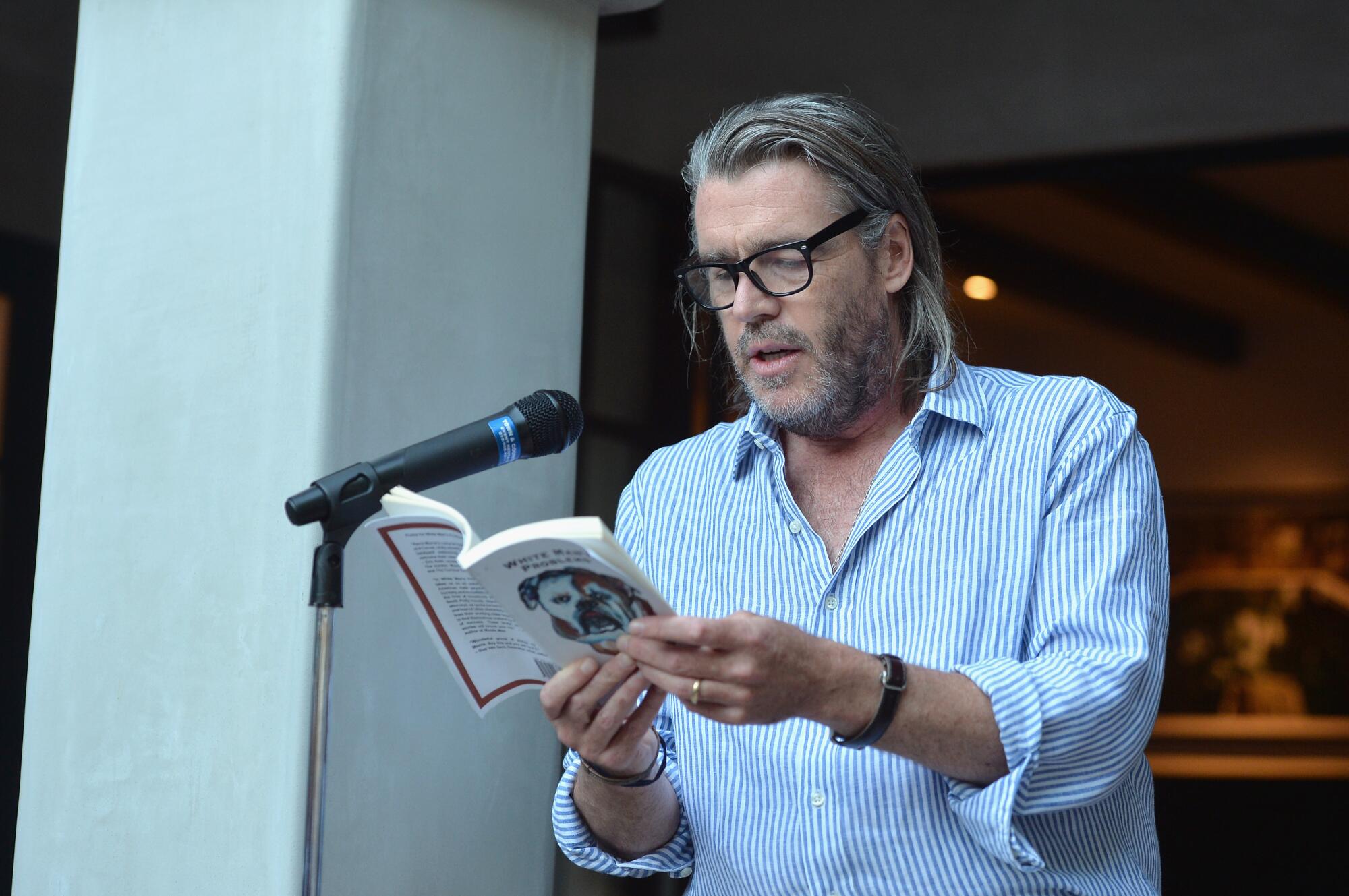

By 2008, Morris was a bona fide power player in Hollywood, but he decided to go after his dream of becoming a writer.

Morris wrote a book of short stories. After an agent responded to his manuscript telling him, “No offense, but these are just white man’s problems,” Morris turned the critique into the title “White Man’s Problems” and self-published the collection.

McConaughey, who helped voice the audiobook, gave Morris a vintage typewriter with a page already loaded with three words: “just keep typin,” a fitting tweak to one of the actor’s favorite maxims.

Morris explored the largely disregarded psyche of the modern American man, telling a local blog in 2014 that they “are basically all f—ed up.”

“Most of us have never been to war, are wealthy compared to the rest of the population of the Earth, our country and our parents, and we have what strikes most people as self-indulgent problems,” Morris said. “But, nevertheless, the pain is real.”

His ability to illuminate flawed men on the page caught the eye of literary agent Jane von Mehren. She brokered a two-book deal that included his first novel, “All Joe Knight.”

In Morris’ literary fiction, characters flirted with affairs, lied, lusted and broke the law. USA Today praised “All Joe Knight” as John Updike “revised for the Trump era.” “Out pours a life story that’s filled with memories of divorce, strippers, pedophile priests, race-based fights on the court and more,” said the review. Morris’ second novel, “Gettysburg,” which came out in 2019, is partly a satire of Hollywood and partly a meditation on American history.

Von Mehren singled out Morris’ ability to write about complicated characters that “aren’t always likable.”

“Some people would look at them,” Von Mehren said in an email, “and say they ‘are horrible human beings.’”

Joe Biden stood in the backyard of a Pacific Palisades home two weeks before Thanksgiving in 2019 and condemned “the vindictiveness” of Donald Trump.

About 125 donors gathered around a swimming pool, including Morris, who forked over $2,800 to attend. For all his wealth, Morris was then a sporadic political donor, and, according to federal records, appears to have given only once before in a presidential race — $2,300 to Obama for America.

After the fundraiser, where they first crossed paths, Morris and Hunter Biden met at the latter’s Hollywood Hills rental, and so began a two-track relationship.

Morris began giving legal advice “from Day 1,” said Lowell. “And they became deeper and more meaningful friends.”

With Morris, Biden said, “I did not feel as if I had to explain or make excuses.”

“One of the most important things in recovery is the ability for you to be honest with yourself and to be honest with people around you. And I immediately felt a comfort level with Kevin,” said Biden, explaining that Morris would not sit in judgment or have “an angle.”

Biden faced a tangle of problems: years of tax returns that had gone unfiled, let alone paid; crippling personal finances; and questions about his foreign business dealings, particularly his seat on the board of Burisma, the Ukrainian natural gas company that he joined in 2014 while his father was vice president. The younger Biden was paid millions by the company.

Morris’ Pacific Palisades home became Hunter Biden’s mission control — and remains so to this day.

In early 2020, Morris convened a “crisis meeting,” where over 2½ hours a group of at least 10 people discussed Biden’s affairs, according to the summary of an interview that one of Biden’s accountants gave to federal investigators.

The urgency of that period was clear in an email that Morris wrote to accountants and Biden about Biden’s outstanding tax returns on Feb. 7, 2020, three weeks before the elder Biden’s victory in the South Carolina primary revived his flagging presidential campaign. The email and other investigative records were released by congressional committees scrutinizing Biden’s business affairs.

“We are under considerable risk personally and politically to get the returns in,” Morris wrote to a partner at Edward White & Co., a Woodland Hills-based accounting firm.

Republicans have pointed to the email as proof that Morris’ motives extend beyond friendship to preventing a scandal from tainting Joe Biden’s presidential campaign. An attorney for Morris declined to comment on the email.

Around that time, Morris paid $160,000 in an attempt to clear Hunter Biden’s 2015 tax bill, according to the congressional records.

That payment appears to have marked the opening of the spigot on years of loans. The full extent of Morris’ financial support and its terms are not clear.

Morris has lent Hunter Biden at least $4.9 million through 2022, with more than $1.2 million coming in 2020 for housing, legal fees, car payments and payments to advisors. Congressional testimony indicates that the 2020 loan carries interest and requires payments to Morris starting in 2025. The bulk of the loans for tax payments came in October 2021.

The loans have caught the attention of GOP lawmakers.

With the influx of cash, Biden wiped out his IRS bill by paying off more than $2 million of taxes, penalties and interest.

“The loans that Kevin has made to Hunter were negotiated at arm’s length and were counseled by each of them having their own attorneys,” said Lowell.

At first Morris did not share much with his brothers about his work with Biden. Dennis Morris said that around early 2020 his daughter went out to California and stayed at her uncle’s home. One day, Morris had friends over to watch a Philadelphia Eagles game.

“She said, ‘I met Uncle Kevin’s friend Hunter,’” Dennis Morris recalled. “I think he’s Hunter Biden.” She added that she met Biden’s then–pregnant wife, Melissa Cohen.

“And then [Morris] sent me a picture — him and Hunter on the porch in the Palisades,” Dennis Morris recalled.

Morris soon welcomed Biden into his family orbit.

Dennis Morris said he and his brother would call Biden, often leaving messages of encouragement, like, “We got your back.” Their mother, Betsy, would talk to Cohen “all the time” about her pregnancy and motherhood.

During the frenzy of late March 2020, when much of society shut down during the early weeks of the pandemic, Cohen gave birth to a son, Joseph Robinette Biden IV, or Beau, at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, according to birth records.

At one point, Biden and his wife came to visit Morris’ mother, who lived near the Delaware-Pennsylvania border. As Morris was leaving, according to a brother, his mother leaned in to kiss her son. “Take care of them and take care of that baby,” she told him.

Two years ago, Morris reached his own inflection point.

He secured a deal around 2021 worth more than $900 million when ViacomCBS’ MTV Entertainment Studios agreed to extend the “South Park” run on Comedy Central through 2027. As part of the arrangement, Stone and Parker would produce 14 “South Park’’ made-for-streaming movies to run on the subscription streaming service Paramount+. It also includes production budgets, tipping the entire deal well over the $1-billion mark.

Around that time, Morris also left the firm he founded.

By then, Morris Yorn had 25 lawyers, 55 employees, and annual billings exceeding $55 million, according to those knowledgeable about the firm’s finances.

“I think he felt it was the right time to transition out,” said Liner, Morris’ friend who also represented him in his exit. “There was just a realization that this was not where he wanted to be spending his time.”

The only clients that Morris retained when he departed were Parker and Stone.

With some friends, he launched a production company called Media Courthouse Documentary Collective, an homage to his Pennsylvania hometown, Media. And he joined forces with his brothers to open a private-equity group that focuses on philanthropy and investments around Media.

As he was marshaling his next moves, a curveball had already arrived.

The laptop scandal dropped in the final weeks before election day 2020.

Biden had long been public about his addiction issues and had a memoir on his journey to recovery slated for publication in 2021. But the trove of data purportedly gleaned from the laptop — nude photos at the Chateau Marmont and other hotels, selfies of crack binges, homemade sex videos, texts and emails from his business dealings — threw his years of excess and iniquity into graphic relief.

The demise of Biden’s digital privacy appears to have been a turning point for Morris — propelling his counsel into a crusade.

He hired multiple forensic specialists and investigators to help unravel what happened with “the laptop,” including looking into John Paul Mac Isaac, the computer repairman in Delaware who maintained that in 2019, Biden dropped off some damaged laptops and never picked them up. Mac Isaac eventually shared a copy of a hard drive with a lawyer for Trump attorney Rudolph W. Giuliani and others.

Morris suggests an alternate theory: that Mac Isaac, the Trump-supporting, legally blind computer repairman, was a Trojan horse for a right-wing scheme to broadcast the worst of Biden’s digital life, according to text messages filed in L.A. County Superior Court last spring.

Morris‘ “contextualized theory” of how Biden’s private data became public fodder is that a clone of data was made from Biden’s laptop while he was undergoing ketamine therapy to treat addiction in Massachusetts in 2019. The clone was given to political consultant and Trump acolyte Roger Stone. From there, according to the theory, it was eventually dropped off at Mac Isaac’s shop.

Stone wrote the foreword to a book by Dr. Keith Ablow, a Fox News contributor and the doctor who was treating Biden with ketamine. Ablow’s Newburyport, Mass., office was raided by Drug Enforcement Administration agents in 2020, and among the items seized was one of Biden’s laptops, which was returned a month later. (Ablow was never charged with a crime and has denied wrongdoing, but his medical license was suspended a year earlier, following allegations of sexual impropriety with patients and illegally diverting prescription drugs.)

Morris suggested in the text messages that the laptop seized at Ablow’s office was the “Rosetta stone” with an “uninterrupted chain of custody.” Presumably that device could be used to analyze subsequent sets of data that purported to be from Biden’s laptop.

“There is real data out there for sure. It’s just a matter of corrupted data and original data mixed,” Morris wrote in the text messages.

Ablow said Morris’ laptop theory “is without any basis in fact whatsoever,” adding, “I never shared Hunter Biden’s laptop with anyone.”

Mac Isaac wrote a book in 2022 that outlines his side of handling the laptop, in which he asserts, “I’m not a spy, a Russian hacker, a liar or an evil person coldly motivated by politics.”

Stone called Morris’ alternative theory of the laptop “a delusional fairy tale.”

“If there is any proof of that whatsoever they should present it,” Stone said, noting that he also received a subpoena from Biden’s lawyer and called it a “wild fishing expedition.”

Morris and the documentary crew also traveled to Serbia in the fall of 2021.

There, they visited the set where an Irish-born filmmaker, Phelim McAleer, was shooting “My Son Hunter,” a film caricaturing the Biden family that was distributed by the conservative news outlet Breitbart.

“I spent a couple of days with him,” said McAleer, explaining that he allowed Morris and his crew to film on the set and even dined with the documentary’s director and cameraman. Morris told McAleer that he was a recovering addict and that he was retiring from law and pursuing his love of documentaries.

McAleer sat for interviews but said he grew wary when he was asked questions like, “What was the real history of the laptop? What did I know about the history of the laptop?”

Only later, McAleer contended, did he learn that Morris was also serving as Biden’s lawyer.

“He was out there looking for information and evidence for his client while he was pretending to be something he was not,” McAleer said. McAleer filed a complaint with the state agency that regulates attorneys in California.

An attorney for Morris did not comment on the incident.

Morris had made a name for himself representing Hollywood stars, but his personal and financial support for Biden has catapulted him into the public eye like never before.

He has become an object of curiosity on Fox News and conservative media, which have chronicled his wealth and Hollywood connections.

Morris alleges that he’s been doxxed. His private jet is tracked online, Congress has sought to question him, and photographers have waited outside his home. In July, images of him smoking marijuana on his front porch were splashed across the Daily Mail and the New York Post, with the headline, “Hunter Biden’s ‘sugar brother’ lawyer Kevin Morris rips bong as first son visits him.”

Few have fixated on Morris more than Garrett Ziegler.

A former Trump White House staffer, Ziegler became known for escorting Trump lawyer Sidney Powell and retired Lt. Gen. Michael Flynn to the Oval Office for a now-infamous December 2020 meeting where attendees discussed seizing voting machines to overturn Joe Biden’s victory.

Ziegler founded the nonprofit Marco Polo, billing the group as an “opposition research group for the American people,” although he largely focuses on the Biden family.

Ziegler’s group has posted a cache of Hunter Biden’s emails; a trove of personal photos, including several nude images; WhatsApp messages; and a full copy of his sister Ashley Biden’s diary, which was stolen from her in Florida around the time of a rehab stint.

Ziegler also has mocked Morris’ appearance and berated him for lending money to Biden.

In April, Morris sued Ziegler and his group in L.A. County Superior Court, accusing him of doxxing, harassment and invasion of privacy.

Ziegler’s antagonizing of Morris has continued since. He compared Morris’ recruiting of lawyers like Lowell to assist Biden’s defense as “a high-end stripper operation” where paid advisors “get up on the stripper pole and Kevin Morris is flowing singles.”

In a podcast last summer, Ziegler claimed that his group posted “the address of [Morris’] many estates” to help “other researchers.”

“Why is Morris footing the bills? Very good question,” Ziegler said in a podcast last year. “Morris is buying leverage over the U.S. first family with these payments,” Ziegler later asserted without evidence.

Los Angeles is a city swarming with Democratic boldfaced names eager to shell out millions in support of President Biden. But many here are loath to attach themselves to his only living son.

Some friends and former colleagues of Morris have distanced themselves from him. Many declined to speak on the record or at all about his ties to Biden, fearing they also would be caught up in the whirlpool of media coverage, harassment or worse.

But others see his public support for Hunter Biden as part of his personal makeup.

“Kevin’s never lost sight of who he is, where he comes from,” Brian Morris said, explaining it as an ethic of loyalty: “If your buddy’s in a scrap, you are in there right next to him,” he added. “Your buddy needs a dollar? You give it to him.”

Morris’ brothers and friends pointed to his record of quiet largess: helping to pay others’ bills and mortgages, covering funeral expenses for scores of families and giving loans to cash-strapped associates. Some of his generosity has been publicized. For instance, he and his brothers gave $1 million to the youth center they frequented in childhood.

And Dennis Morris pointed to Hunter Biden’s fraternal bond with their wider family. After their mother died, Biden traveled to visit the family in Pennsylvania. During the visit, Biden put his father on the speakerphone, and the president expressed his condolences.

Then President Biden talked to the Morris brothers’ stepfather privately over the phone about grief.

“Obviously, when the most powerful man in the world takes time out to talk to your grieving stepdad, you are appreciative,” Dennis Morris said.

Barry Sheerman, a member of the British Parliament since 1979 who had Morris as an intern in the mid-1980s and has remained close friends, said that with Biden and others, Morris wants to offer the hand that others extended to him.

“If he finds out someone is struggling, he dedicates himself to helping them,” Sheerman told The Times, adding that Morris “doesn’t seek public approval for what he does.”

Still, many who have crossed paths with Morris, including some who worked closely for years, have scratched their heads over the depth of his work with Biden.

“Kevin has done this time and time again, but obviously not to this extreme,” said a longtime friend.

“He is on a journey. It’s just not the journey that I knew him on,” said an entertainment executive with whom Morris has socialized and worked with over the years.

Altschuler, a mentor for about 40 years dating back to his undergraduate years at Cornell, said Morris sees himself “as a combatant in a war.”

“Let me say this categorically — I detect no ulterior motive in Kevin,” Altschuler said. “He’s absolutely convinced that Hunter Biden is being grievously wronged with attempts to wreck his life, and that is Kevin’s motivation.”

The last year did not go the way either Biden or Morris had imagined.

In June, Biden agreed to plead guilty to two misdemeanors — failure to pay his 2017 and 2018 taxes, the same taxes that Morris had lent him money to pay off two years ago.

The deal, which averted prosecution on a gun-related charge, promised a tidy resolution after a five-year criminal investigation.

But around the time the deal was unveiled, two IRS agents who claimed to be whistleblowers had come forward and alleged there was political interference in the long-running Biden investigation. The agents gave rounds of press interviews and answered questions before Congress. Records from their long-running inquiry were also made public.

The trove of investigative records hardly focused on Morris, but they revealed new details about his role, including that agents had wanted to question about 10 people connected to Hunter Biden, including Morris, on one day in December 2020. Only one of the witnesses gave a “substantive interview” — an Arkansas-based business associate of Biden.

Agents questioned Jim Biden, the president’s brother, in 2022 and asked him about Morris, among other issues. Jim Biden told agents that he met Morris a few times — including at a picnic at Hunter Biden’s home. When agents appear to have pressed him about Morris’ motives, he had little insight.

“Morris was helping [Hunter Biden] a lot, but James [Biden] didn’t know why. James B thought that this might have been because of his ego,” according to federal agents’ memorandum.

Citing the IRS agents’ claims of political interference, Republicans on Capitol Hill lambasted the plea agreement as a sweetheart deal for the president’s son.

Biden, along with Morris, arrived in Delaware court expecting to enter his plea and close the matter. Instead, the deal imploded.

Biden’s attorneys and federal prosecutors failed to hammer out a new deal, and David Weiss, the U.S. attorney in Delaware, was given the additional post of special counsel to investigate the matter.

Biden’s fortunes have worsened since.

The special counsel has filed two indictments against Biden over the same conduct that was part of the plea deal.

In Delaware, Biden faces charges related to his lying on a federal form about his drug use. In L.A., Biden has been indicted on charges including failing to pay his taxes on time and tax evasion for allegedly misclassifying personal expenses, like college tuition and money paid to an exotic dancer, as business expenses.

Biden has countered with a multi-front war in the court system, and by several accounts Morris is the quarterback helming the legal team.

Speaking generally about Morris, Biden told The Times: “He’s a fighter, he is fearless.”

Starting in September, Biden sued Ziegler, accusing him of running an “unhinged and obsessed campaign against” him and his family. Then he sued Giuliani, accusing Trump’s former lawyer of “disseminating and generally obsessing over data … that was taken or stolen.”

Next Biden sued the IRS, contending that the two agents had improperly disclosed his confidential tax records in press interviews as part of “a campaign to publicly smear Mr. Biden,” according to the suit. Then he sued Patrick Byrne, the former chief executive of Overstock.com, for defamation over Byrne’s claim that Biden had solicited a bribe from Iran.

Biden is also pressing ahead with a countersuit against Mac Isaac, the Delaware computer repair shop owner.

On the criminal defense front, Biden’s legal team fired off a suite of motions to dismiss the Delaware charges as politically motivated, vindictive, unconstitutional and barred by an agreement that prosecutors signed last year and that his lawyers assert is still valid and binding.

Lowell is representing Biden in all five civil cases, defending him against the two indictments, and representing him before Congress.

It’s not clear how Lowell and other lawyers are being compensated.

And while Morris’ name is not on the pleadings, the cases are a manifestation of an aggressive strategy that he has long advocated, according to those familiar with Biden’s legal team.

Outside the Capitol in December, Hunter Biden strode to the lectern and blasted “MAGA Republicans” for turning his addiction-fueled mistakes into an “absurd” campaign to discredit his father.

That night, after the House voted along party lines to open the impeachment inquiry into President Biden, Morris headed 10 miles south of the Capitol to the blackjack tables at a casino in Maryland and left with a stack of cash winnings.

Not all Democrats embraced Biden’s snubbing the subpoena.

“If you’re sitting in the White House right now, you’re like, ‘Please, Hunter Biden, we know your dad loves you. Please stop talking in public,’” former White House Press Secretary Jen Psaki said on “Meet The Press.”

Fox News host Maria Bartiromo devoted a segment to Morris and presented a photo of him standing by Biden at the Capitol news conference.

Bartiromo asked Rep. Jason Smith (R-Mo.), one of the chief proponents of pursuing a Biden impeachment, “What’s the relationship here?”

That question will persist. Congress has pressed Morris to appear for an interview.

Biden believes that Morris will remain with him for the long haul. At times, he said, the two have fought, even screamed at each other amid this very public maelstrom.

“But it’s with the knowledge that no matter what, that I know that if I need him and most likely before I even know that I need him, he will be there and likewise me with him,” Biden said.

Times staff writers Melissa Gomez and Courtney Subramanian contributed to this report.