Running for president, Ronald Reagan repeatedly promised to “make America great again.” Thirty-six years later, Donald Trump grabbed the line and became the great plagiarizer.

“Reagan was the original MAGA. No question. Trump swiped the line from Reagan,” political consultant, speechwriter and author Ken Khachigian told me.

Reagan used the line in three Republican National Convention speeches and repeatedly on campaign trails.

But you’d never catch Reagan wearing a red baseball cap with MAGA inscribed across the front. He was born to wear a plain white cowboy hat.

“Donald Trump recognized the penetrating strength of the Gipper’s communication and co-opted the words into the very definition of his political persona,” Khachigican writes in his recently published autobiography, “Behind Closed Doors:

In the Room with Reagan and Nixon.”

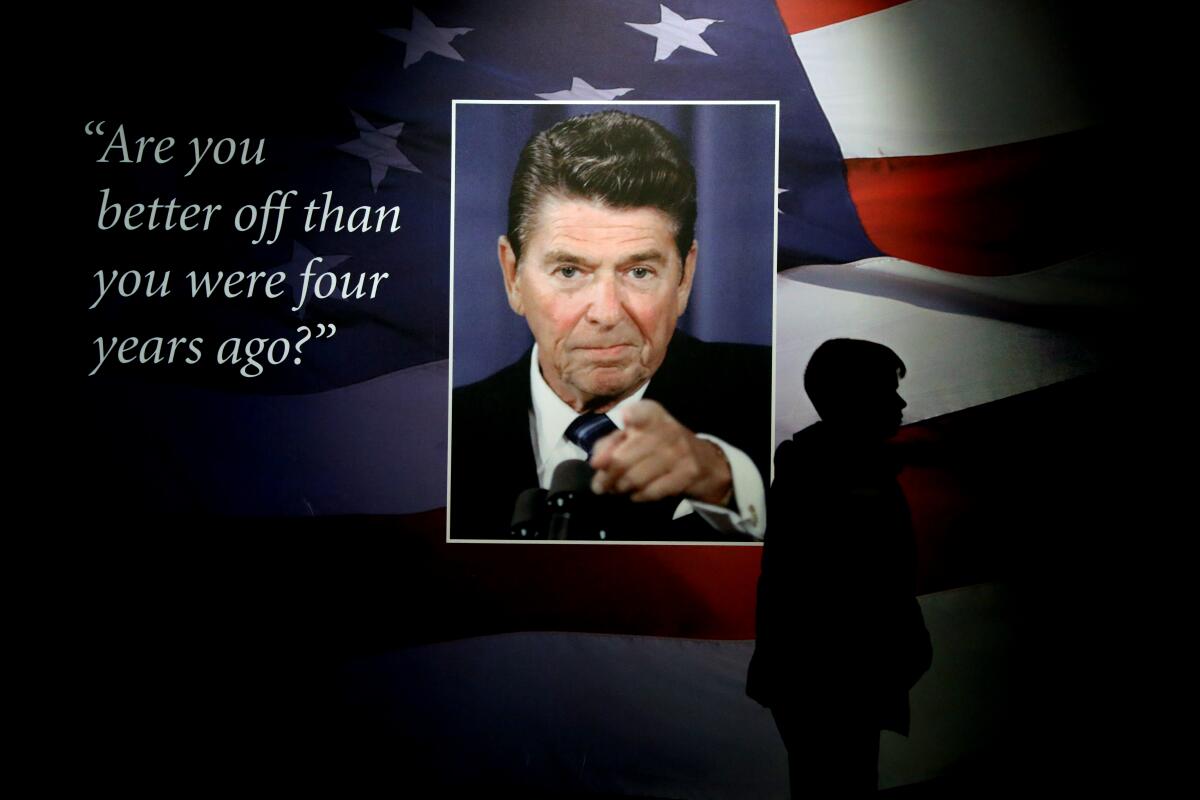

Toward the end of his winning campaign this fall, Trump also ripped off a more famous Reagan line from 1980: “Ask yourself, are you better off than you were four years ago?”

Here’s how Reagan often put it to voters:

“Look around you — at the price of food, the price of gasoline, the interest rates you have to pay to buy a house, the amount of taxes taken out of your paycheck. Look around, then ask yourself: Are you really better off than you were in 1976?”

Any of that sound familiar?

But even when he was attacking, Reagan came across as upbeat and positive, directly opposite of the whiny, doomsday tone of Trump. At least that’s my observation, having covered Reagan for 20 years as a governor, candidate and president.

“When I unleashed that line,” Khachigian writes, “I never dreamed it would serve as Reagan’s defining message in 1980 and resonate for decades as a gold standard in political rhetoric.”

Khachigican suspects he sold Trump on the “four years ago” comparison in an op-ed piece he wrote for the Wall Street Journal less than three weeks before the election.

“Then Trump started using it a lot more” against Vice President Kamala Harris, Khachigian told a book-signing gathering last week in Sacramento.

In his very readable book, Khachigian writes candidly about behind-the-scenes, face-to-face dealings as a speechwriter and confidant of Reagan and Nixon.

They’re the only two Californians ever elected president, and Khachigian — a farm kid from Visalia in the San Joaquin Valley — lived a political junkie’s dream by working closely with both during their good and bad times.

Khachigian is a pleasant, easygoing guy who’s a conservative hardliner and a political hardballer — but he made sure only the president’s views wound up in a speech.

In the book, Khachigian doesn’t pull punches in condemning backbiting and turf building by ambitious presidential aides.

“Like any intoxicant, power in the nation’s capital can have a destructive effect —turning good men and women against each other, fostering distrust and betrayal as well as feeding the intense need for identity, attention and recognition,” he writes. “Of the seven deadly sins, all but sloth emerge from the seduction that beckons.”

But he adds that “wielding power and mining the force of the institution for self-aggrandizement weren’t unique to the Reagan White House.”

Khachigian, 80, got his political start while attending Columbia Law School in New York. He volunteered in Nixon’s 1968 presidential race and was hired by the campaign’s speechwriter, Pat Buchanan, who initially suspected the kid of being a spy for rival Nelson Rockefeller.

As a White House wordsmith during the final gloomy days of the Watergate scandal in 1974, young Khachigian wrote Nixon a memo “futilely pleading that he reject resignation,” he writes in the book.

“‘Resignation is not in your character,’ I argued, and ‘[your] instinct surely must be to fight.’”

Khachigian says he still believes that: “A lot of Republicans were cowardly. They didn’t want to have to take a [congressional] vote” on impeachment. So they didn’t support the president.

One small section of the book especially was intriguing. There has always been speculation about whether President Ford agreed to pardon Nixon if he stepped aside. An anecdote reported by Khachigian indicates a deal might have existed.

Shortly before the resignation, Khachigian recalls talking with the president’s attorney, Fred Buzhardt. Khachigian told him he hoped Nixon would be left alone if he quit.

“Fred looked directly and piercingly at me with words I would never forget,” Khachigian writes. “‘Don’t worry, that’s part of it. He’s not leaving without those understandings being reached.’ He repeated, ‘Don’t worry about that, Ken.’

“I remembered them a month later when Gerald Ford issued Nixon’s pardon.”

After Nixon returned to San Clemente, Khachigian helped him write his autobiography — basically ghostwrote it.

Nixon connected Khachigian to one of his early-career strategists, California-based political consultant Stu Spencer. And Spencer hired Khachigian as Reagan’s 1980 speechwriter after he took over the floundering campaign as chief advisor.

“The best kept secret,” Khachigian writes, was Nixon’s steady stream of memos to Reagan offering advice, most of it helpful. They kept it mum “to deprive [President] Carter an opening to resurrect Watergate.”

The campaign’s unofficial “chief of staff” was Nancy Reagan — ”Mommy,” as her husband affectionately called her — whose life was dedicated to fiercely protecting and advancing her beloved “Ronnie.”

Khachigian writes about an angry Nancy Reagan berating White House chief of staff James Baker for ordering the president’s speechwriter not to attack Democratic candidate Walter Mondale by name during the 1984 reelection campaign. Baker told the first lady such rhetoric would not be presidential.

“That’s enough, Jim. Now get this straight,” she’s quoted by Khachigian. “Ronnie will refer to Mondale by name — not just as ‘my opponent.’ I don’t want any more ‘Huckleberry Finn’ speeches. There will be no more white picket fences. Is that clear?”

Reagan’s speeches quickly got tougher.

“At every opportunity, I threw in Mondale’s name and made it sound like a profanity,” Khachigian writes.

He thought Baker was too moderate and prevented Reagan — in the name of “pragmatism” — from achieving his conservative goals of lower taxes and smaller government.

I saw it differently: Baker enabled Reagan to compromise with congressional Democrats and accomplish what he never could have as a conservative ideologue.

Regardless, Reagan’s winning rhetoric — largely crafted by Khachigian — lives on today through Trump. Unfortunately.