Some of President-elect Donald Trump’s Cabinet nominations have raised hopes that his trade and other economic actions will not be wildly disruptive or bring back inflation. But that could turn out to be wishful thinking.

Based on the record of his first term in the Oval Office and on his current statements of his intent, Trump’s second term may see a break from the largely bipartisan consensus that has shaped U.S. economic policy for more than 50 years.

That consensus has centered on a push for more foreign trade, less government regulation of business, tax cuts and other fiscal stimulus when necessary to sustain steady growth and low unemployment. Though Republicans tended to put more emphasis on one element or another than Democrats, the overall thrust remained pretty much the same.

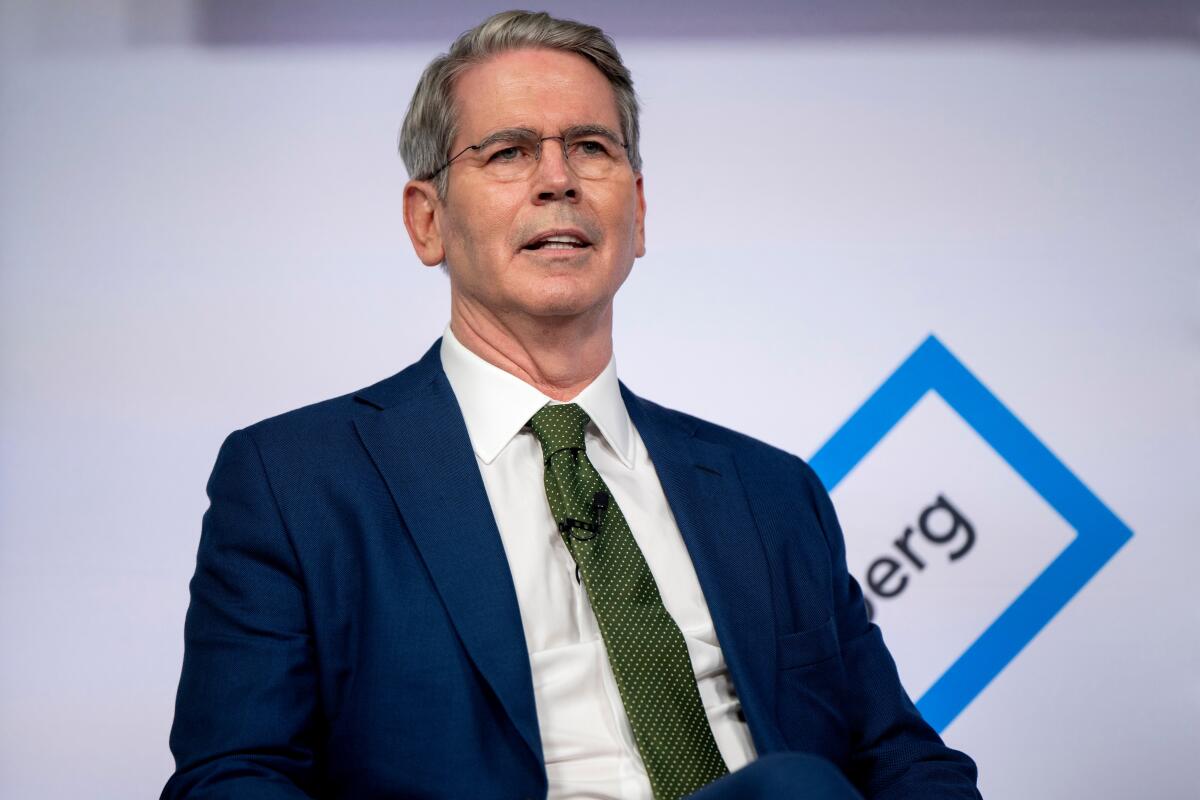

And supporters of that approach took heart when Trump picked billionaire investor Scott Bessent to be his Treasury secretary. Bessent is a familiar name in the hedge fund world, and for some years he worked under the longtime financier and Democratic backer George Soros. Wall Street immediately cheered the selection by pushing up stock prices.

But on the very next trading day after naming Bessent, Trump announced plans to slap 25% tariffs on Canada and Mexico, as well as 10% more on Chinese goods that are already taxed heavily thanks to the trade war he launched in his first term. The goal was to press Mexico in particular to curb border inflows of fentanyl and migrants.

On the campaign trail, Trump proposed tariffs of up to 20% on all countries and 60% on China.

And on Wednesday, Trump said he would bring back Peter Navarro as a senior trade and manufacturing advisor. The fiery China hawk and former UC Irvine professor clashed with other, more moderate top officials in Trump’s first administration. Navarro was recently released from a four-month prison sentence for defying a congressional subpoena related to the Jan. 6 Capitol attack in 2021. (Navarro didn’t respond to text messages seeking comment.)

“If there was any illusion that the choice of Bessent was going to have an ameliorating effect, that got completely blown out of the water,” said Christopher Rupkey, chief economist at the Wall Street research firm Fwdbonds, predicting more fireworks inside the White House, and outside.

“At some point companies are going to go down to Mar-a-Lago (Trump’s estate) and start to complain loudly,” Rupkey said.

In some respects, Trump’s picks for other Cabinet and major economic-related posts in the White House are also a reprisal of his past performance. There are billionaires, notably Elon Musk, named to head a new department on government efficiency; and traditional conservative economists, such as Kevin Hassett, an alumnus of the American Enterprise Institute, who’s been tapped as director of the National Economic Council, a key role in helping formulate White House economic policies.

And at least some of Trump’s nominees are unlikely candidates, particularly Rep. Lori Chavez-DeRemer (R-Oregon), a Latina who has been a rare Republican supporter of greater organizing rights for unions and had the backing of the Teamsters’ leader.

Heidi Shierholz, president of the left-leaning Economic Policy Institute, applauded Trump’s choice of Chavez-DeRemer as secretary of Labor. Chavez-DeRemer has personal connections to the labor movement. But Shierholz wondered what difference she would be able to make. As with Trump’s Labor secretary in his first term, Alex Acosta, she said Chavez-DeRemer was likely to face significant constraints.

“Trump doesn’t suffer dissent; I don’t have high hopes,” Shierholz said.

“Trump’s eclectic style is fully on exhibit in his Cabinet selections,” said Michael Genovese, author of “The Modern Presidency” and head of the Global Policy Institute at Loyola Marymount University. Even so, he said, “the single common denominator in staff and cabinet selection has been loyalty to Donald Trump. … Trump likes to break things, and he has a lot of folks around him who are more than willing to do the breaking.”

Genovese added: “After his frustrations in the first term where insiders undermined the president’s wishes, he will not tolerate such insubordination in term two.”

Moreover, if Trump’s first term provides a guide, his economic and other policies also may be strongly influenced by a kitchen cabinet of informal advisors and an inner circle of confidantes who share his instincts and views on the economy, particularly his predilection for tariffs as a primary weapon for rebuilding American manufacturing and reducing the U.S. trade deficit.

That impulse toward protectionism and away from the global economy could again set off a major fight inside the GOP as two fundamentally conflicting visions collide.

One focuses on boosting domestic manufacturing, which could be helped by a reversal of trade deficits and a lessening role of the dollar. This “America First” strategy seeks a return to the policies that prevailed early in the last century, when U.S. manufacturing was protected from overseas competition by high tariff walls — that is, high surcharges on imported goods that make them too expensive to compete with U.S. products.

The other approach, more favored by Wall Street, sees an open global market as offering lower prices for consumers and more opportunities for American companies to tap capital markets and expand abroad.

American multinational firms and their affiliates spent about $200 billion on plant and equipment in 2022 and employed some 14 million outside the U.S., the latest year for which data were available from the Commerce Department. Their overall foreign sales: more than $8 trillion, with almost half in Europe and most of the rest in Asia.

Globalists are not convinced that reducing the trade deficit is vital to U.S. interests.

And they note that countries previously responded to high U.S. tariffs by increasing their own taxes on American goods. Economists say that will almost certainly push up consumer price inflation, which has been receding from nearly double digits in 2022 but remains about a percentage point above policymakers’ 2% target for core inflation.

“All tariffs on all products all the time, of 10% to 20%, are pretty alarming to business leaders,” said Jeffrey Sonnenfeld, a professor at the Yale School of Management and an expert on leadership and corporate governance.

Sonnenfeld said Trump’s appointment of Bessent was “hugely reassuring” and suggested that he could, if confirmed by the Senate as expected, bring a moderating influence.

“Scott Bessent is definitely the adult in the room,” Sonnenfeld said, contrasting him with another wealthy Wall Street boss, Howard Lutnick, Trump’s choice for Commerce secretary.

“There’ll be some natural tension between Lutnick and Bessent as things unfold,” he said.

Michael Pettis, an American professor of finance at Peking University in Beijing and a nonresident senior fellow at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, agreed that Bessent was an excellent choice.

As in the first term, China is likely to be a key target of Trump’s foreign investment and trade battles, including tariffs, which President Biden has kept in place while adding more restrictions on Chinese access to American technologies.

“Scott Bessent understands the economy systemically,” Pettis said. “I think he could be a very positive influence. The real question is, to what extent he will determine Treasury and economic policy generally?”

Bessent has talked about tariffs as a negotiating tool, and more recently argued for targeted tariff increases on national security grounds as well as to establish a more level playing field. And he spoke of a need for a “more activist approach internationally.”

In recent days, Trump also appointed as the United States trade representative Jamieson Greer, the former chief of staff for Robert Lighthizer, the USTR in Trump’s first term who renegotiated the North American Free Trade Agreement and pushed through tough trade measures against China.

What’s clear to some who have been following Trump’s appointments is that he wants to avoid the internecine warring in the White House that marked the early months of his first term and to be more forceful in implementing his agenda.

“I think there is a strong economic plan that reasonable minds may disagree on. Tariffs will be part of the overarching plan,” said Daniel Ujczo, senior counsel specializing in trade at the Ohio-based law firm Thompson Hine.

“This administration will not be handcuffed by the old orthodoxy of what you can or cannot do,” he said. “I think there’s a recognition in this administration that these voters elected them to do something. Voters were less concerned about what that something was.”