A landmark California law signed last year to enact the strongest privacy rules in the country and regulate the online marketplace of personal data is caught in a tug of war between industry lobbyists who want to weaken it and consumer groups that say it doesn’t go far enough.

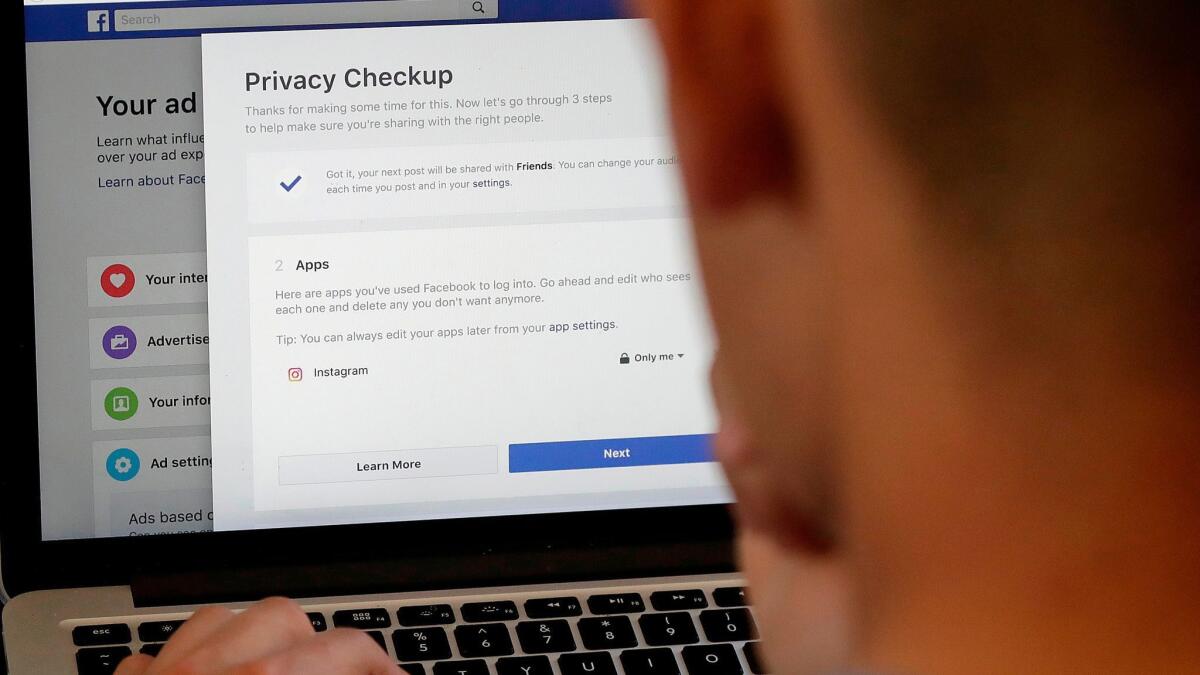

The California Consumer Privacy Act, which takes effect in January, will grant people in the state new rights to control the information that businesses gather about them and sell at a time when tech companies such as Facebook, Google and Amazon are facing pressure to change their data collection and advertising practices.

But as state Atty. Gen. Xavier Becerra puts together new regulations to implement the law, advocacy groups are seeking more protections for consumers and business groups are working to rein it in, arguing that it will stifle competition and burden companies struggling to comply with a much broader privacy law, the General Data Protection Regulation in the European Union.

Legislative Republicans and Democrats have introduced at least eight bills that would build on California’s privacy rules or expand them, giving consumers the right to sue over abuses or requiring companies to obtain permission from customers before collecting data. Business and tech industry lobbyists are fighting some of the most sweeping proposals and asking the attorney general to narrow the scope of his rules, which must be written by July 2020.

While the debate plays out in California legislative committees and public forums, it has also filtered into discussions at tech conferences and in Congress about the creation of a federal privacy law and whether it should limit states in setting their own regulations. Industry lobbyists have counted at least 30 statewide proposals that they argue could create a patchwork of disparate rules nationwide.

Testifying at a recent hearing before the House Energy and Commerce Committee, Roslyn Layton of the conservative-leaning American Enterprise Institute said California had already set the bar.

“It isn’t fair that one state gets to dictate for everyone else,” she said.

Amid the flurry of activity, Assemblyman Ed Chau, who co-authored the law, has met with congressional allies such as House Speaker Nancy Pelosi (D-San Francisco), Sen. Kamala Harris (D-Calif.) and Rep. Zoe Lofgren (D-San Jose) in an attempt to prevent federal efforts from undermining the state law.

“Data is now our new oil — no, it is more valuable than oil,” Chau said, using a favorite expression of privacy advocates. “I don’t want to go backward because I think California will serve as a model for the rest of the nation, and I want to drive home that point.”

So far, he seems to have support for his cause.

Pelosi wants a federal privacy bill to set nationwide standards. But “Americans have benefited from state privacy and data breach laws, so their role as policy innovator and law enforcer must be respected,” said her spokesman, Drew Hammill.

An unlikely leader in the state’s resistance to the Trump administration on tech, immigration and climate change policies, Chau, a business-aligned Democrat from Arcadia, rarely wades into the limelight.

But he first took on internet privacy in 2017 when he proposed that California embrace a set of federal regulations rolled back that year by President Trump and Congress. Like the federal rules, his initial bill would have required internet service providers such as Verizon, Comcast and AT&T to get permission from customers before using, selling or allowing access to their information.

The bill sunk after a behind-the-scenes battle that pitted major telecom companies against state internet service providers and consumer privacy advocates. A trio of activists — San Francisco real estate developer Alastair Mactaggart, former CIA analyst Mary Ross and finance industry executive Rick Arney — then teamed up in an attempt to put their own proposal before voters with a 2018 ballot initiative.

As their group, Californians for Consumer Privacy, collected signatures, support for new privacy rules grew among consumers. Equifax and Uber were hit by high-profile data breaches. Facebook Chief Executive Mark Zuckerberg was called to testify before Congress in a federal probe into how data firm Cambridge Analytica obtained the information of tens of millions of the platform’s users to help the Trump presidential campaign.

“The stars were somewhat aligned,” said Chau, who along with other state legislators struck a deal with activists to enact major privacy rules and avoid a battle at the ballot box. The result was a state law that some saw as a good compromise, or “GDPR light,” Chau said, referencing the European Union’s far-ranging General Data Protection Regulation, which took full effect in May.

Unlike GDPR, which requires companies to ask consumers to “opt in” to having their data collected or sold and sets high fines for violations, California’s privacy law gives people the chance to “opt out” and have their data deleted, and sets smaller penalties for violators.

Both laws allow people to ask companies what personal information is collected about them and why, and request that their data be deleted. They include some protections to prevent discrimination against customers and require companies to obtain permission from parents before gathering personal data from children under 16.

Among those working to keep the California law intact is Mactaggart, who says it was crafted with business in mind.

“We drew on the work of experts who have been working on this for a decade,” he said at a recent Senate hearing, pushing back against claims that the law was crafted in a rush.

But businesses and trade associations say that some of the law’s definitions are ambiguous and could lead to unintended consequences and inconsistent implementation. For example, critics say it is unclear whether the law’s definition of “personal information” would allow anyone in a household to request someone’s data, potentially putting information in the hands of an estranged spouse or roommate.

“This is going to cause great consumer harm, and it puts businesses in a Catch-22,” said Sarah Boot of the California Chamber of Commerce at a February public forum held by the attorney general’s office. “They could be liable if they don’t respond to a request they find suspicious, but they can also be liable if they disclose specific pieces of sensitive information about a consumer to a fraudster.”

Owners of small and midsize businesses say the cost of hiring additional staff to comply with the law will be a burden. To head off the potential financial hit, some businesses are seeking exemptions, including publishers that rely on personal data for ad revenue, gaming companies that use the information to prevent harassment and nonprofits that analyze it to meet fundraising goals.

Consumer advocacy groups want to ensure that people have a clear and easy way to “globally opt out” of having their personal data collected and sold, regardless of whether they can decide to opt out for certain types of data.

It is critically important, they say, to close loopholes in the law that could create a “pay for privacy” model in California, giving companies permission to charge higher prices or offer lesser quality services to customers if they exercise their privacy rights.

Sweeping changes are being weighed at the Capitol, where Gov. Gavin Newsom has lauded state lawmakers for passing the privacy law and has earmarked $4.8 million for the attorney general to enact the rules.

Sen. Hannah-Beth Jackson (D-Santa Barbara), who has for years called for stricter regulation of tech companies, worked with Becerra to introduce legislation that would remove a provision permitting companies to avoid penalties if they notify consumers of data breaches within 30 days and allow consumers to seek legal remedies.

At a Senate committee hearing Tuesday, she criticized large businesses that have argued that giving consumers the right to sue would lead to costly litigation, saying Facebook complaining of an $800,000 lawsuit was “laughable.”

“They spend $800,000 on their office Christmas party,” she said.

The most far-reaching proposal, the Privacy for All bill, was introduced by Assemblywoman Buffy Wicks (D-Oakland) with the support of more than 30 privacy groups, including the American Civil Liberties Union of California, Common Sense Kids Action, the Council on American-Islamic Relations and the Electronic Frontier Foundation. It would bring the state law closer in line with GDPR, creating an “opt-in” option for consumers and stronger protections against “pay for privacy” practices that some say target black and Latino communities.

Meanwhile, Assemblyman Jordan Cunningham (R-Templeton) has introduced a package of proposals with three fellow Republicans to require social media platforms to permanently delete data at the request of the user and ensure businesses notify consumers of a breach within 72 hours.

“We are in a world now that everyone is on social media, uses phones, has smart speakers,” he said. “There is a lot of cool tech evolving really rapidly, but somewhat lost on that is the needs of consumers.”

California bill aims to revive broadband privacy rules that were killed by Trump and Congress »

Follow @jazmineulloa on Twitter.