Reviews and recommendations are unbiased and products are independently selected. Postmedia may earn an affiliate commission from purchases made through links on this page.

When Drew Goddard’s savvy 2012 horror-comedy Cabin in the Woods hit theatres, author Stephen Graham Jones found himself in high demand.

Goddard’s film, once described by the late Roger Ebert as “a puzzle for horror fans to solve,” is part homage and part postmodern subversion of the slasher flick. As an acclaimed and bestselling author of savvy horror, Jones was often called upon to introduce the film during its festival run.

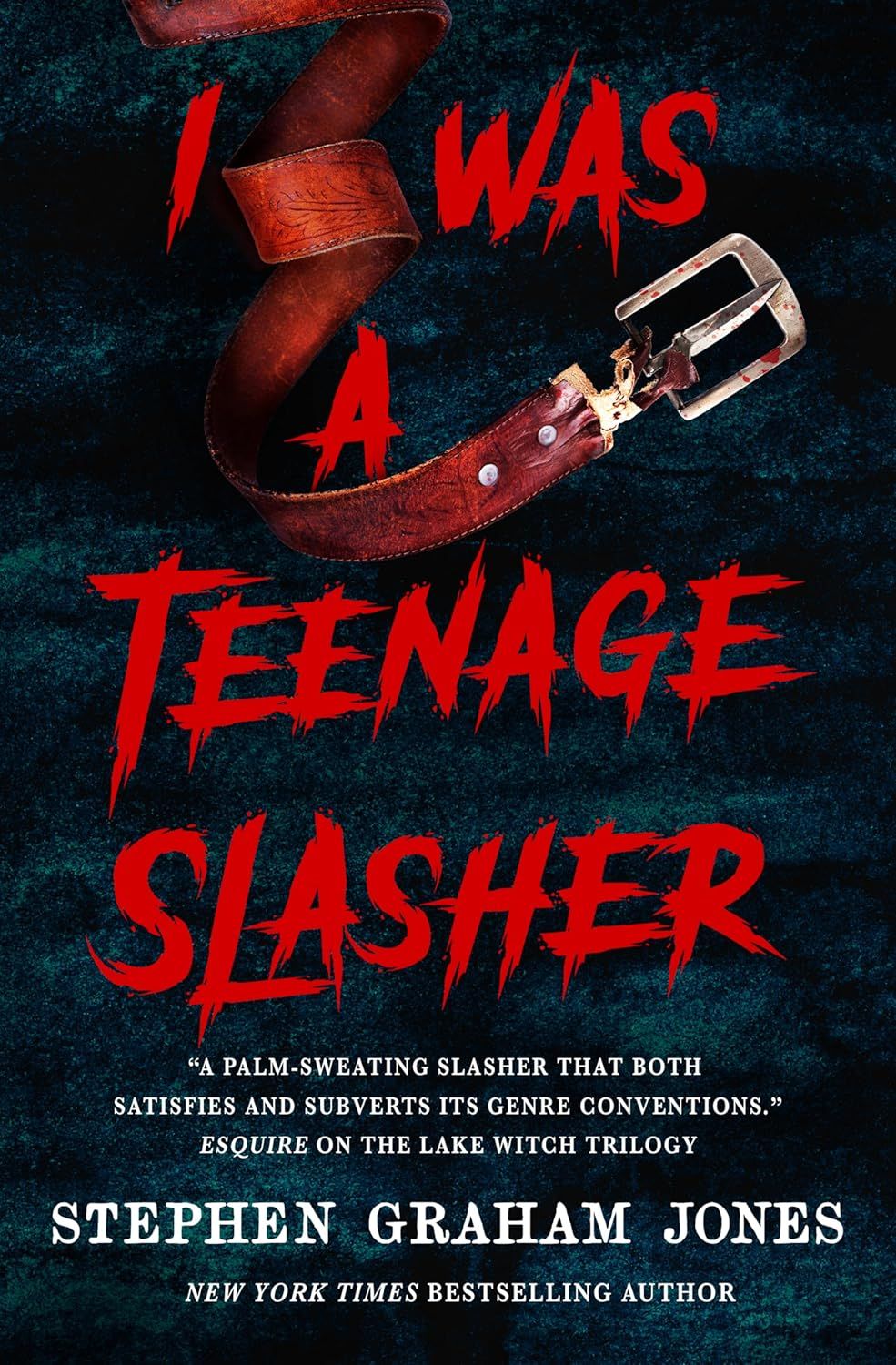

“So I feel like I deeply engaged in trying to figure out a way to contextualize it for audiences who weren’t familiar with that kind of stuff,” says Jones, in an interview with Postmedia from his home in Colorado. “At the time, I didn’t feel like there was any room left over. Cabin in the Woods had kind of sucked all the air in the room, which is wonderful when a story, a film, a novel or whatever can do that. But I felt like like it had told the definitive last word on the how and (the) why of a slasher. At the same time, I was always suspicious that maybe they hadn’t taken up all the air. Maybe there was a little space. So with I Was A Teenage Slasher, I was finally able to stumble into what felt like new terrain as far as, not autopsying the slasher because it’s alive, but plumbing its depths and finding new ways to do things that have the same result.”

I Was A Teenage Slasher is the latest novel for the prolific writer. According to the acknowledgments, it had its beginnings on a 14-hour flight the author was taking to Dubai, but he placed the action in the familiar setting of small-town South Texas circa 1980s. Jones not only grew up in small-town South Texas in the 1980s, but that was also a golden era for slasher flicks, hair-metal and other pop-culture touchstones that the author references in the book.

Jones also writes in the acknowledgments that of the many characters he has created over the years, our protagonist/antagonist Tolly Driver is “the same idiot I am.” Tolly is a funny and smart but somewhat awkward and unpopular teen who is still struggling to come to terms with the death of his father. His best friend is the resourceful Amber Dennison, an Indigenous teen who eventually becomes a guide of sorts due to her knowledge of the slasher genre as Tolly begins to transform.

As with many a good horror film, the nastiness begins with a mean-spirited prank. A very drunk Tolly is out of his depth at a pool party when some popular kids try to rein in his rambunctious activities with a punitive prank that almost kills him. Through some horror-esque plot turns, Tolly is eventually turned into a killer who possesses some otherworldly powers and impulses that he can’t control. The body count begins to rise.

Amber, who is well-schooled in the construct of the slasher flick, begins to unravel what the two can expect while trying to prevent slasher-mode Tolly from taking ultimate revenge on those who wronged him.

So we are introduced to the slasher red herrings and character stereotypes, not because Jones engages in hackneyed writing but because Tolly and Amber begin to notice how reality and the people around them start to fold into horror-movie cliches. What results is a clever, funny and often surprisingly touching novel that brings in traces of coming-of-age, meta-fiction and, of course, the horror genre. There are numerous sequences where Jones outlines outlandish kill scenes with painstaking detail, but at the centre of the novel is the well-developed friendship between two protagonists whose loyalties are tested as corpses begin to pile up.

When Jones was Tolly’s age, he was an avid horror movie buff, but he admits he didn’t have much interest in conducting a writerly dissection of the genre until later.

“I think back then I was just soaking them in,” says Jones, who will be appearing in Calgary this week as part of Wordfest. “I felt lucky to be watching these videotapes, that’s where I watched most of them was on videotape. I felt lucky to be able to rent them and just live in a world for 95 minutes at a time, or however long it was. So, no, I wasn’t thinking: If I take this piece out, what happens to the rest of it? I didn’t start thinking those thoughts until the late 1990s.”

By that point, Jones had begun writing novels and was “thinking about story in a different way.”

“I was standing in the middle of a landscape trying to shoulder around and make room for myself and see what I could do that would matter,” he says. “Also, (Wes Craven’s horror film) Scream had come out by then, in 1996, and spawned a whole little renaissance of neo-slashers — Urban Legend, I Know What You Did Last Summer, Cherry Falls and all that kind of stuff — and those were all a blast as well, but they were a bast in almost a metaphysical way where the characters existed in a world that was familiar with the slasher and the dynamics of the slasher. That’s what got me thinking about the slasher in a different, more meaningful way. The second novel I wrote, Demon Theory, I wrote in 1999 and it was directly interfacing with the slasher, how the slasher is and can a slasher still work.”

Jones began publishing in 2000 and has since amassed a bibliography that includes more than 30 novels, short-story collections and comic books. Novels such as 2020’s The Only Good Indians and Night of the Mannequins and 2021’s My Heart is a Chainsaw have seen Jones turn into a master of deconstructing the subgenre. A member of the Blackfeet Tribe of Montana, Jones says including aspects of that culture in his work is his “default setting.”

“Even if I have a story in which I never say anybody is Blackfeet or native or anything, it’s still an Indian story to me,” he says. “It doesn’t have to directly interface the politics of identity or repatriation or any of that stuff for it to be not just Indian but Blackfeet. It’s my default setting and it is important to me, but I don’t have a list of checkboxes that I have to hit when I go into a story. I just let the story go where it’s going to go and along the way. I’ve found places to grind the axes that I need to grind.”

Part of the joy of reading Teenage Slasher, particularly for those who are the same age as Jones, is the heaping helping of pop-culture references that fill the pages. Because Tolly is not familiar with the horror genre himself, the touchstones tend to be of the non-horror sort. But there are plenty, everything from the cheerfully awful 1985 martial arts film Gymkata to the 1982 Oscar-winner The Officer and a Gentleman, to Nintendo’s 1984 Duck Hunt video game. Numerous hair-metal bands also get a shoutout.

As for the horror genre in general, Jones says while it may have been regarded as less-than-serious at one point, attitudes are changing. Work such as Jordan Peele’s 2017 film Get Out and Victor LaValle’s 2016 novella The Ballad of Black Tom was the “one-two punch” that had people waking up to the fact that the genre is not on the periphery of legitimate writing, he says.

“We’re part of the conversation,” he says. “We’re in dialogue with current issues. We are processing this age’s anxieties and fears and given them back in the form of media. To me, that’s the function of fiction, of literature. That’s what we’re supposed to be. Yeah, genre – specifically horror – gets maligned and I suspect that’s because the emotion it provokes is considered not lofty enough. Not turning the lights off at 2 a.m. is not valued. Making somebody ill at ease or physically nauseous is considered base. I don’t think that’s the case. I think any reaction you can provoke with art is a good reaction.”

An Evening with Stephen Graham Jones and Jeff VanderMeer will be held Saturday, Oct. 19 at 7:30 p.m. at Memorial Park Library as part of Wordfest’s Imaginairium. He will also participate in Culture Slash on Oct. 20 at 3:30 p.m. at Memorial Park Library.