Before Santa Monica was covered with concrete, traffic and pricey real estate, Cristyne Lawson remembers a town where open fields met the shore and a tight-knit community of Black Americans lived, worked and worshiped just blocks from the beach.

“Growing up here was just a joy. Everybody knew everybody,” said Lawson, 85, who lives near the Ocean Park-area house where she was raised. “There were lots of vacant lots and empty space — people used to grow corn on some of it — and you could wander all over. When I was 8 or 9, if I was walking down Main Street around 4 p.m., someone was sure to come out and say, ‘Your Aunt Mamie’s looking for you’ — that’s what everyone called my grandmother — because if someone saw me out at that time they knew I should be home. I can’t imagine that happening today.”

Not everyone has such fond memories, however, even in Lawson’s family, partly because “the Black community wasn’t happening here in Santa Monica,” she said. “They didn’t think it was the place to be.”

That’s because African Americans were largely discouraged from opening businesses that catered to Black clientele in Santa Monica, said historian Alison Rose Jefferson, author of “Living the California Dream: African American Leisure Sites During the Jim Crow Era.”

African Americans began moving to California in the late 1800s to escape the overt racism in the South and find better opportunities, Jefferson said. But discrimination still stymied Santa Monica’s Black community, and eventually erased many of its neighborhoods in the name of “progress” and redevelopment, such as the Belmar Triangle, where the city’s Civic Center, auditorium and new Historic Belmar Park stand today.

The street named Belmar Place doesn’t even exist anymore — it ran north and south between Pico Boulevard and Main Street and is now covered by Santa Monica’s south Civic Center area — and many of the buildings where African Americans lived and worked are gone, such as the Black-owned business La Bonita. A lodge and bathhouse, La Bonita provided rooms, a restaurant, a tennis court, “hot and cold” showers, and even “a complete line of bathing suits and accessories” to its clientele between 1914 and the early 1930s, Jefferson said, when such accommodations were not readily available to Black travelers.

California’s civil rights laws made it illegal to discriminate at public accommodations, but those laws were poorly enforced, Jefferson said. “As in Los Angeles, African Americans in Santa Monica learned by experience that they were not welcome at many hotels, restaurants, theaters and other establishments.”

La Bonita was sometimes listed in “The Negro Motorist Green Book,” which from 1936 to 1963 named restaurants, hotels, gas stations and other businesses in the U.S. that welcomed African American travelers, Jefferson said.

Nearby, Belmar Place also housed the Sunset Lodge for the African American Elks Club.

These places are all gone now but there are still several sites you can visit on an easy walk starting at Historic Belmar Park at 4th and Pico streets. The former city parking lot is now a 3.5-acre multipurpose sports field. It’s circled by a wide walking path studded with 16 interpretive panels outlining the city’s African American history between 1900 and the 1960s in Belmar and surrounding areas, such as Ocean Park and the Black neighborhoods further north that were razed so the 10 Freeway could be extended to the ocean. Jefferson was commissioned to create the panels as part of the Belmar History + Art project, the city’s effort to confront what Mayor Sue Himmelrich, in a city announcement, described as “a painful part of our local history.” The project, dedicated Feb. 28, includes a public art installation by Los Angeles conceptual artist April Banks called “A Resurrection in Four Stanzas.”

“This park and the dedicated artwork represent the displaced Santa Monica families and offer a starting point for the healing process of our Black community,” Robbie Jones, a local historian and Belmar History + Art project advisory committee member, said in the same announcement. “It is encouraging to be a part of this project dedicated to sharing the history and memories of our community that were overlooked for many years.”

Racism was subtler and more institutionalized in Santa Monica, Jefferson said.

Black children went to the same public schools as white students, but the school district didn’t hire Black teachers until the mid-1950s and permitted white teachers to use racist texts promoting the “inferiority” of Black people, she said. The local Sears store hired Black people as janitors but not sales clerks until the mid-1950s. Santa Monica didn’t hire Black police officers until the 1940s, Jefferson said, or Black firefighters until the 1960s.

The historian will be discussing the Belmar History + Art project on March 20, during an online symposium as Occidental College’s Institute for the Study of Los Angeles Scholar in Residence. The event, “Promised Land, Hallowed Ground: Commemorative Justice and Making Change in Community Heritage Preservation in Southern California, Part 1,” is free.

Lawson, the retired dean of dance at the California Institute of Arts, grew up as things were starting to change.

When Santa Monica’s first Black doctor, Marcus Tucker, started his practice around 1930, he wasn’t permitted in the downtown medical offices, Lawson recalled, so he eventually built his own building on Pico Boulevard. And her mother, Bernice Stout Lawson, was a concert pianist and music teacher who got her degree at USC but had to teach in Los Angeles schools.

Her father, Hilliard Lawson, was a mail carrier who also ran a catering business and was Santa Monica’s second Black city councilman from 1973 to 1975. (The city’s first Black city councilman and, later, mayor was former Santa Monica police officer and college administrator Nat Trives, who served from 1971 to 1979.)

Lawson herself spent much of her adulthood dancing and traveling, studying at the Juilliard School, performing with the Martha Graham and Alvin Ailey dance troupes and even dancing with Ailey in the movie “Carmen Jones.” But she grew up just a few blocks from the Bay Street Beach, in the Ocean Park neighborhood where her family held sway as church leaders, teachers and musicians.

“I didn’t know any racism when I was a kid,” she said. “We had the church and all the people who went to the church and all our family around the church. … But the Black people who lived here did not live in a completely segregated society. There were all kinds of people who lived around us. We certainly went to our own churches, but there were white people who lived here too and Japanese … before they sent them away” during World War II.

Most of the Black community worked as domestics or janitors in white homes or businesses, Lawson said. “Everybody knew they couldn’t be on the other side of Montana (Avenue) after dark because they didn’t want you over there unless you worked there,” she said.

Lawson’s family was an exception. Her grandfather was the Rev. James Stout, the first pastor of the Phillips Chapel Christian Methodist Episcopal Church, the first C.M.E. church west of Texas and the first African-American church in Santa Monica.

Lawson never knew her grandfather, who died before she was born, but she grew up in her grandmother’s home with her parents just a block from the church, which was the center of worship, culture and entertainment for many in Santa Monica’s Black community.

“I remember seeing Sister Rosetta Tharpe in the church; she had golden glasses when she sang, a gold star in her tooth and a golden guitar,” Lawson said. “There was always something cultural going on and huge Easter egg hunts. There was a large vacant lot behind the church, and we used to have big barbecues that ended with Heaven and Hell parties — in ‘Heaven’ you’d go to a house with soft music, ice cream and cake, and in ‘Hell,’ it was all chili and stuff, with music that was much jumpier.”

Until about the 1950s, it was difficult for African Americans to find entertainment outside their homes and churches in Santa Monica, Jefferson said. Sometimes it just depended on who was working the register, she said, so they could never be sure where they could sit in a restaurant or even whether they would be allowed inside.

There was only one nightclub in Santa Monica where African Americans could go dancing in the 1920s, Jefferson wrote in her essay “Reconstruction and Reclamation: The Erased African American Experience in Santa Monica’s History.” That was George W. Caldwell’s Dance Hall at 1816 Third St., where the civic auditorium parking lot is today.

Caldwell’s attracted Black people from all over Los Angeles, Jefferson said, until a group of white homeowners formed the Santa Monica Bay Protective League in 1922 and began lobbying the city to shut it down. The Protective League’s slogan, “A Membership of One Thousand Caucasians,” was focused on keeping Black people out of areas near the beach, Jefferson wrote, and the city eventually complied, “ruling against nightclubs in residential neighborhoods, just to close Caldwell’s down.”

And the reason Caldwell’s was in what was then a residential area? Because the city stopped Black people from opening businesses in commercial areas, especially close to the beach, Jefferson explained.

At the same time Caldwell’s Dance Hall was being shut down, for instance, the Protective League successfully lobbied the city to deny a building permit to a group of African American investors, led by businessmen Charles S. Darden and Norman O. Houston, who wanted to build a Black resort on the beach, where the Shutters on the Beach hotel is now. When the white property owner, William P. Roberts, father-in-law of Culver City founder Harry H. Culver, heard about the controversy, he rescinded the property sale to the Black investment group, Jefferson said. And prominent white businessmen urged other property owners to apply the “Caucasian clause” to their holdings, to prevent the leasing, occupancy or sale of any property to people “not of Caucasian origin,” she added.

From the mid-1920s until the late 1930s, exclusively white beach clubs such as the Casa del Mar tried off and on to restrict access to the beach in front of their clubs to members only, Jefferson said. Consequently, Black beachgoers started to congregate at the Bay Street Beach in Santa Monica, in front of Crescent Bay Park, where they were less likely to be harassed, and many whites began referring to the beach as “the Inkwell,” she added.

The few Black businesses near the water were forced out by city decree. The Viceroy Hotel property at Pico Boulevard and Ocean Avenue, for instance, was once owned by Black entrepreneur Silas White, who started renovating an old building to create the Ebony Beach Club, a project whose supporters included charter member and singer Nat King Cole, Jefferson said.

But the City Council began eminent domain proceedings to condemn the building, ostensibly for a city parking lot, in August 1958, just two months before the hotel was scheduled to open. White fought the proceedings, arguing that the building had been vacant for 13 years before he began his project and that the city had never made a move to take over the property then, but the city prevailed.

By the late 1950s, most of the residents in the Belmar Triangle were “lower-income African Americans, other people of color and whites,” said Jefferson. The neighborhood was torn down, and many of the houses burned, in the 1960s as part of the city’s redevelopment plans, forcing Belmar residents to leave their homes and businesses so the land could be used for a new civic auditorium, and courthouse and the freeway extension.

By then, Lawson was an established dancer, pursuing her career abroad. “Everybody I went to school with became teachers and principals; that’s the way Black people became middle-class in those days,” she said. “I was the only one who went into dancing.”

Her only sibling, Janez Lawson Bordeaux, got her chemical engineering degree at UCLA and became a NASA human computer, the first African American hired into a technical job at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena. But like their mother, Janez never cared for Santa Monica, Lawson said. She and her husband, Theodore, made their home in Brentwood’s Mandeville Canyon, where she lived until her death in 1999. And their mother sold her mother’s property “because she couldn’t stand to be a landlady. She didn’t see this place becoming anything.”

Not Lawson. She feels lucky to have inherited the Ocean Park home her great-aunt refused to sell. “I was always happy here as a kid; I knew it was special,” she said, and she’s glad the city is finally recognizing its Black heritage. “I’ve had people say to me, ‘Why is that Black church sitting down there on Bay Street? How did that get there?’ They’re always so surprised. … I think it’s about time they knew.”

A self-guided walking tour through Santa Monica’s Black history

A few remnants of Santa Monica’s vibrant Black history remain. Here are some landmarks that make for an easy two-mile round-trip walk:

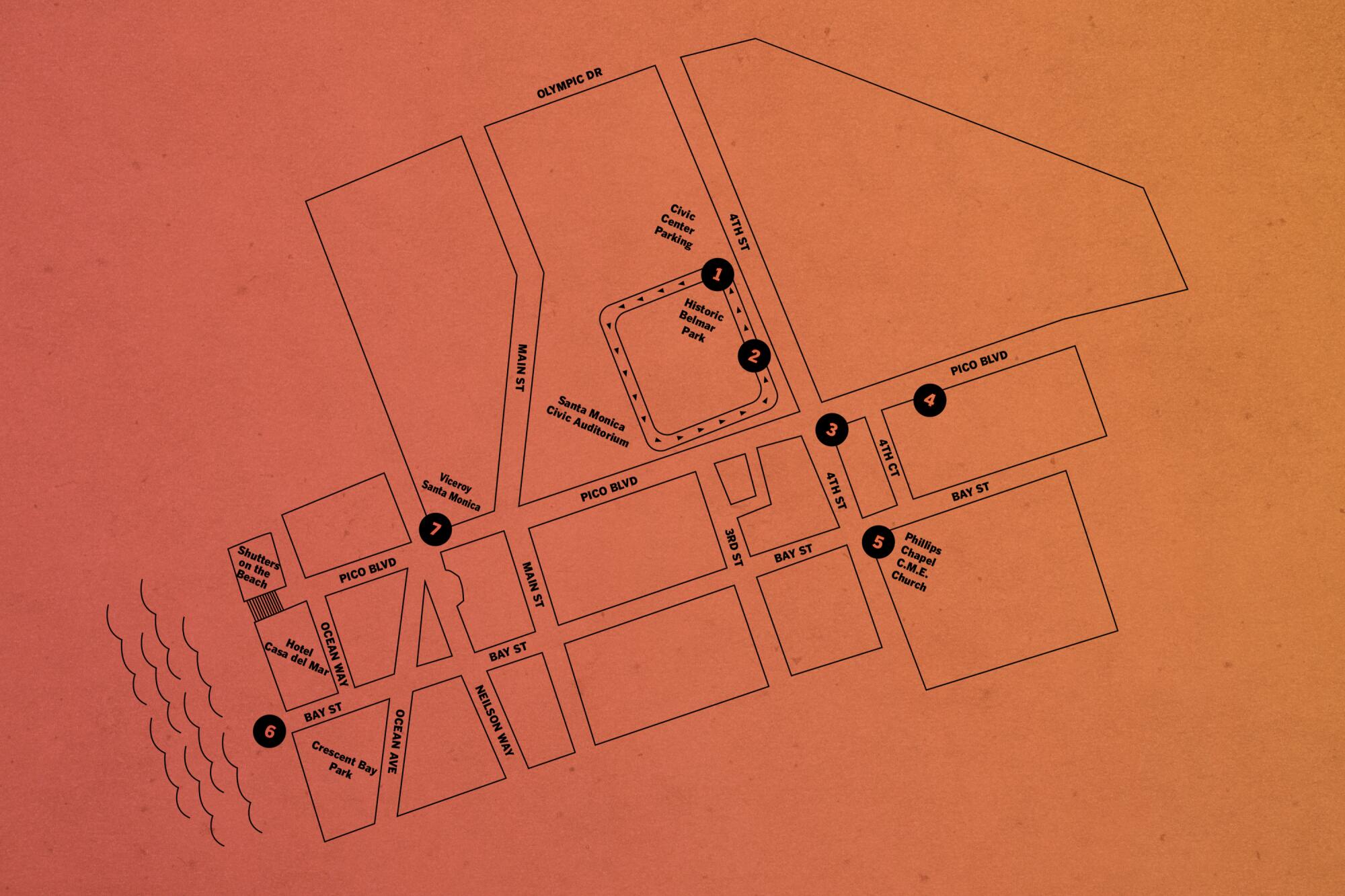

1| Start at Historic Belmar Park, 1840 4th St. (Parking is available nearby.) Circle the park, reading the new interpretive signs to get a sense of the area’s history.

2 | One highlight: “A Resurrection in Four Stanzas,” a sculpture by Los Angeles artist April Banks, honoring the people displaced and the homes destroyed during the city’s “urban renewal,” which eliminated much of its affordable housing.

3 | Across Pico Boulevard, you will find the Murrell Building, built by Manuel Lee Murrell in 1925. Murrell became Santa Monica’s first Black mail carrier and was also an entrepreneur: He and his wife, Julia, lived in one part of the mixed-use building and rented out the rest. Civil rights activist Lloyd C. Allen, the first African American member of Santa Monica’s Recreation and Parks Commission during the 1960s and early 1970s, ran his maintenance and janitorial supply business from there for 25 years until he purchased the building from the Murrells. The Murrell Building was the office space for Santa Monica’s first African American doctor, notes historian Alison Rose Jefferson.

4 | Dr. Marcus O. Tucker moved into the Murrell building because he hadn’t been welcome elsewhere. He would go on to build his own medical offices just up the street, at 424 Pico Blvd. A side note for architectural buffs: Tucker and his wife, Essie, purchased a lot nearby on 20th Street and commissioned famed African American architect Paul R. Williams to design their home, one of the few Williams designs still standing in Santa Monica, Jefferson said.

5 | At Bay and 4th streets, you find Phillips Chapel Christian Methodist Episcopal Church, the cultural center for the African American community in the early 1900s. In the 1940s, the church was remodeled to its present Colonial Revival style, with 11 stained-glass windows featuring the names of the prominent Black families that purchased them.

6 | Head west down Bay Street to the Bay Street Beach and search for the bronze historic plaque on a rock commemorating the stretch of beach popular with the Black community, sometimes referred to as the Inkwell.

7 | Pause outside the Viceroy Hotel on Pico Boulevard. This is the site where Black entrepreneur Silas White tried to open the Ebony Beach Club in 1958. Two months before he was to open, the city began eminent domain proceedings to force the sale of the property, Jefferson said.