The teenagers tucked their hands into their sweatshirt pockets as they shuffled to form a circle. Some gazed at the asphalt, trying to avoid the game they had been drafted to play.

“It’s like hot potato/musical chairs, but with a penis,” said the girl leading the group.

The kids gathered on a spring morning in South Los Angeles were about to get a hands-on lesson in sex education.

Many health experts say that public health problems are best tackled outside the doctor’s office — that fixing the culture that perpetuates them is more effective than changing a single patient’s behavior. For sexual health, that means combating the stigma around sex.

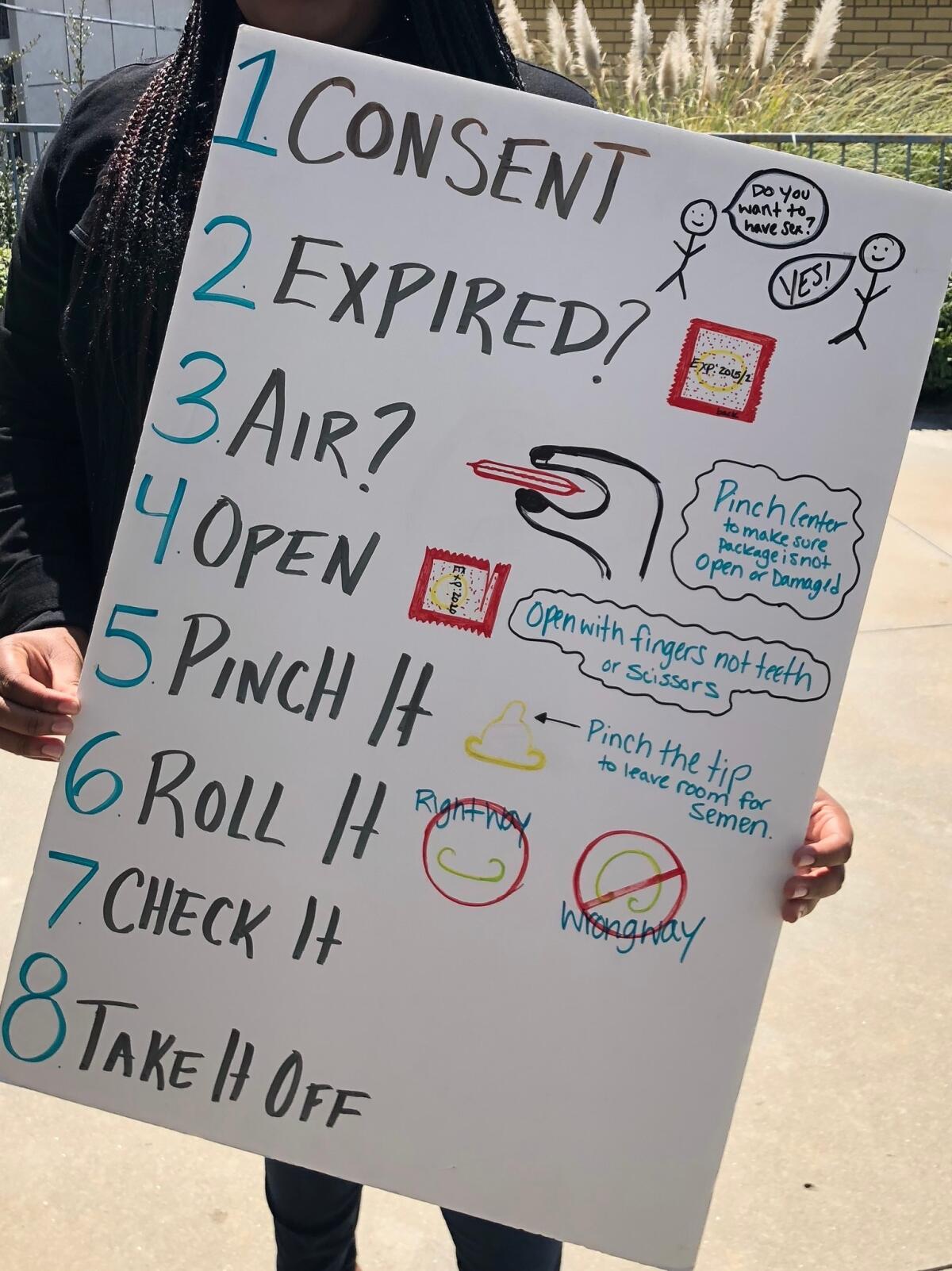

The teenagers, the girl explained, would pass a plastic, life-size penis around the circle. Whoever was holding it when the music stopped would have to unroll a condom onto it, completing each of the eight steps they had been taught a few minutes earlier.

The music started, and the teens looked up.

The recent all-day event, called Spring Into Love, was intended to get high schoolers more comfortable talking about sex. The hope is that an open dialogue will make them more likely to seek out condoms and STD testing, and eventually reduce the spread of disease.

The focus on stigma is just one of many ways Los Angeles County health officials are trying to think outside the box as they struggle to curb rising STD rates. It’s clear that the traditional ways of preventing disease — patients seeing a doctor regularly to get screened and treated — have not been working, said Dr. Jeffrey Gunzenhauser, L.A. County’s interim health officer.

“If that really happened, this problem could be taken care of,” he said.

The county recently created a Center for Health Equity to evaluate the way certain public health issues are intertwined with social factors such as income and education, as well as racial discrimination.

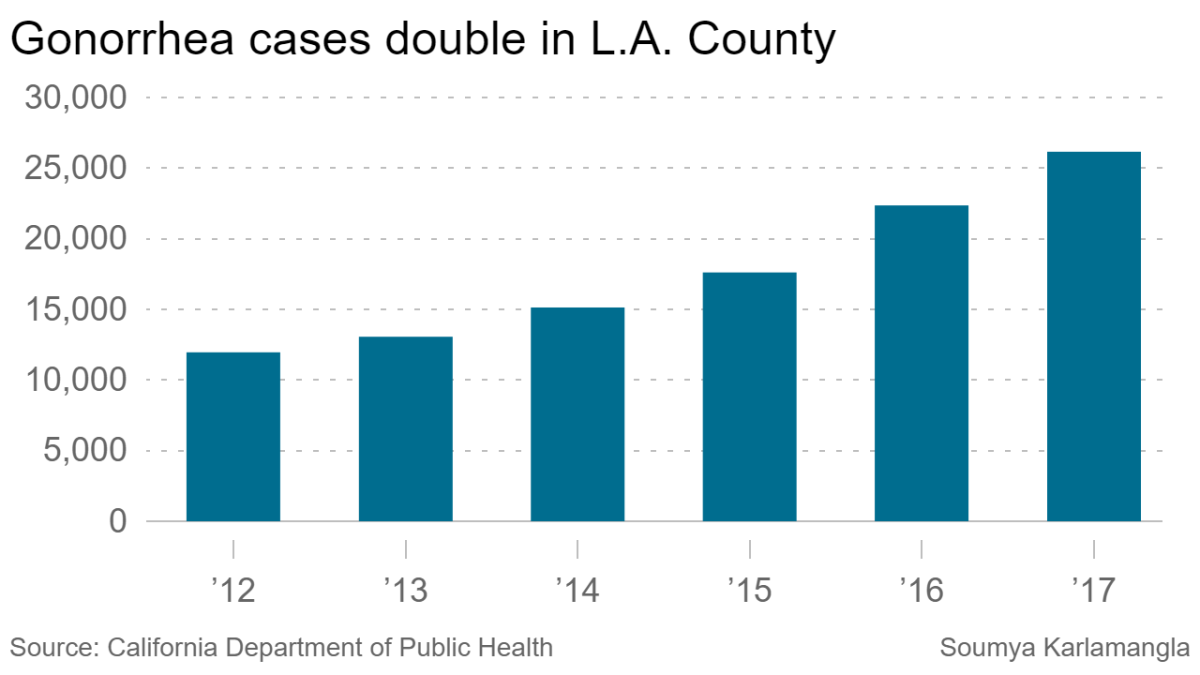

High STD rates are at the top of the center’s list of priorities. In just the past five years, the number of gonorrhea cases in Los Angeles County doubled, with minorities suffering more than most.

“The numbers are only going up,” Gunzenhauser said. “What’s going on is unacceptable.”

“All I heard was ‘Don’t get pregnant’”

The church auditorium was decked out in streamers and balloons. Kids chatted around tables with piles of Mardi Gras beads and condoms at the center.

Spring Into Love, which began five years ago, is the brainchild of a coalition of L.A. County health advocates trying to bring down STD rates. This year’s event, held in late March, included workshops on healthy relationships and body image, as well as free STD testing.

Ashley Deras, 18, showed a group of students how to safely open a condom wrapper. She said her family almost never talked to her about sex.

“Sexual health was something in my household that was taboo,” Deras, a high school senior, said in an interview. “All I heard was, ‘Don’t get pregnant.’”

Other teens at Spring Into Love sought practical information they hadn’t learned in health class. One boy said he hadn’t known he could get STDs from anal sex. Many said their parents would be mad at them for asking questions about sex at all.

“This is such a natural human interaction, and yet it’s so stigmatized,” said Valerie Coachman-Moore, who oversees WeCanStopSTDsLA, the coalition of advocates that put on the event. “People are having sex? Yeah.”

Many say the silence around sex plays a big role in young people’s high rates of STDs. Many feel uncomfortable walking into an STD clinic or talking to their partners about safe practices.

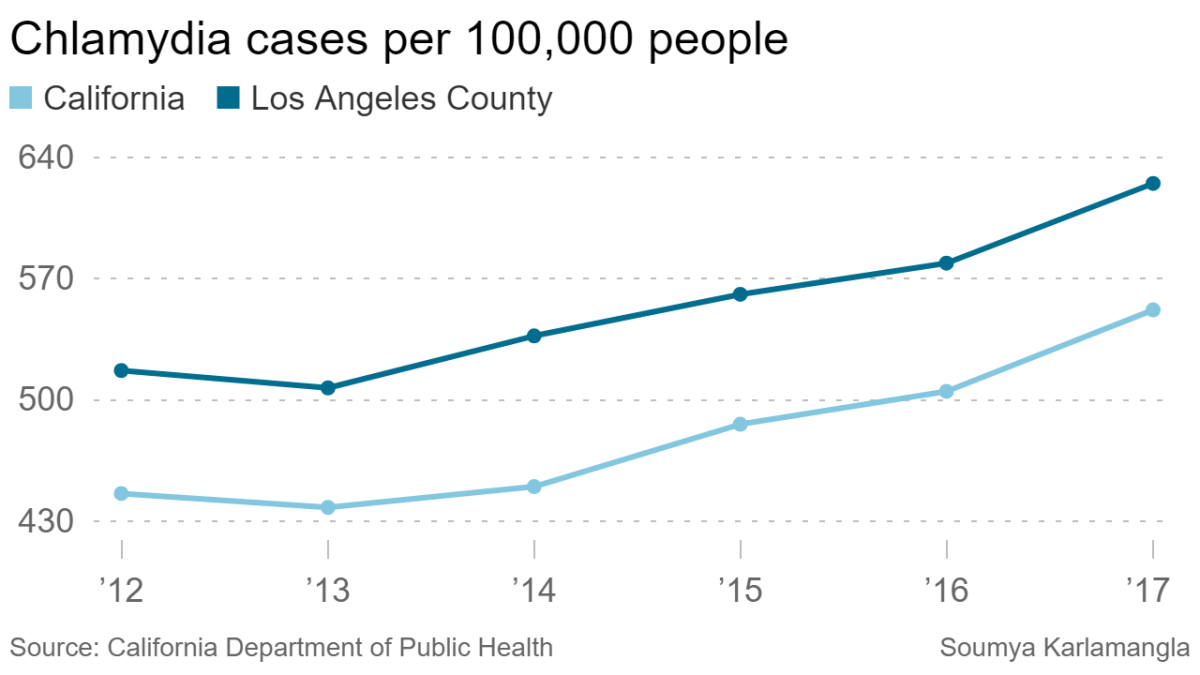

In L.A. County, half of chlamydia cases and a third of gonorrhea cases diagnosed each year are among people between the ages of 15 and 24.

“The one thing I never do, and I hope others don’t as well, is blame these young people for not taking care of themselves,” said Barbara Ferrer, head of L.A. County’s Department of Public Health.

Researchers increasingly view public health problems as shaped by the environments in which people live. Neighborhoods where people of color reside, for example, are more likely to be pollution-ridden and have fewer parks and doctors — factors that directly affect people’s health.

”This is not just their problem, it’s a community problem,” said Jim Rhyne of WeCanStopSTDsLA.

Is systemic racism to blame?

Los Angeles County launched a Center for Health Equity in October to address the idea that “health predominantly happens outside the health care setting,” said its director, Heather Jue Northover, at a recent meeting. “It happens where we live, work, play and pray.”

The center will target five health disparities, including high rates of STDs among certain minority groups.

Nationwide, STD rates have been climbing for the past five years. More people were diagnosed with syphilis, chlamydia or gonorrhea in 2016 than ever before.

Some blame underfunding of STD prevention programs, as well as falling condom usage. There’s also speculation that people are having sex with more partners because of hookup apps.

But the picture is more complicated when it comes to the high STD rates among minorities. Gay and bisexual men make up the vast majority of new syphilis cases. In L.A. County, syphilis rates among African American women are six times higher than white women and three times higher than Latina women.

Northover said that officials need to evaluate what’s called structural or systemic racism, the way housing or education policies may negatively impact people and their health. Studies have found, for example, that people with HIV who had low levels of literacy were less likely to follow their treatment, and that poorer Americans were more likely to engage in risky sexual behavior, increasing their risk of STDs.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention released a white paper in 2010 saying the country could not close disparities in STD rates without addressing “the interpersonal, network, community, and societal influences of disease transmission and health.”

But that’s a tall order given how entrenched many social problems are.

Poverty or a lack of opportunity may be forcing women to exchange sex for resources, leading to the spread of STDs, Northover said. There also tends to be a mistrust of the medical system among African Americans, making them reluctant to seek care. Certain neighborhoods may be excluded from access to healthcare because of geography or finances, she said.

“We need to take a wider lens,” said Northover, who added that she’s still trying to get to the bottom of what’s driving STD rates.

County Supervisor Mark Ridley-Thomas, who represents South Los Angeles, convened several community groups in 2012 to try to bring down STD rates through collaboration. But the still-growing case numbers suggest the approach needs to be reimagined, said Dr. Michael Hochman, a senior health deputy for the supervisor.

“If you keep doing the same thing and expect a different result, then that’s insanity,” Hochman said.

Twitter: @skarlamangla