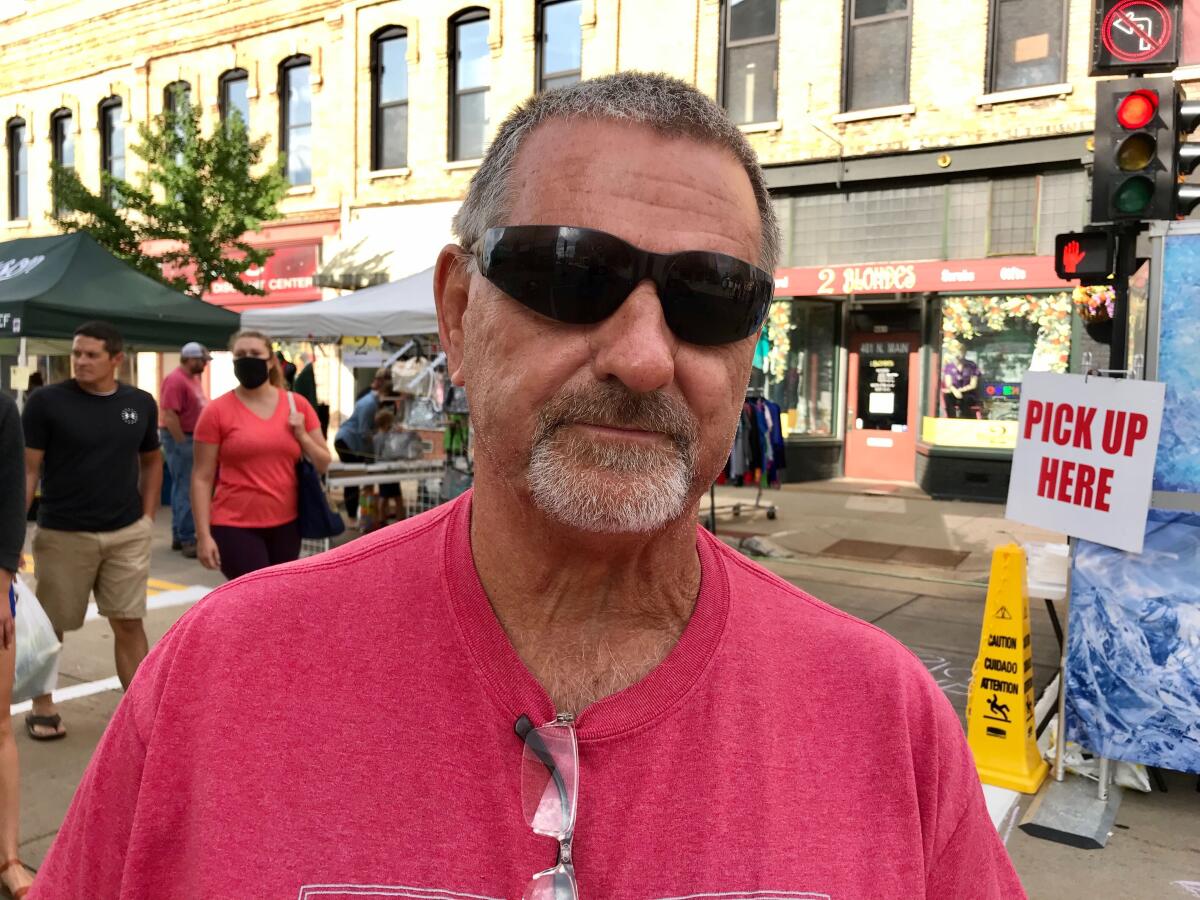

In 2016, a fed-up Patrick Murray cast his presidential ballot for Donald Trump, seeing the brash New Yorker as “somebody new, somebody different, somebody that wasn’t part of the Washington crowd.”

Now, though, Murray’s contempt for the president is abundantly clear, even cloaked behind the mask that swaddled his nose and mouth as he ran errands on a sunny afternoon in northeast Wisconsin’s Fox River Valley.

“My biggest problem with Trump is he’s a pathological liar,” Murray spat out. “I can’t deal with that.”

The 72-year-old retired cop is no fan of Joe Biden who, to Murray, seems like just “another old white guy.” Still, he plans to tune in to the Democratic National Convention, which starts Monday, because just maybe Biden’s running mate, California Sen. Kamala Harris, can bring Murray around to supporting the ticket.

Wisconsin, the land of dairy cows, beer and razor-thin elections, was one of three “blue wall” states that slipped away from Democrats in 2016 — by a combined total of fewer than 78,000 votes. The breakthrough put Trump in the White House, giving him the electoral college votes he needed to win the presidency even as he lost the nationwide popular vote.

The two other states that flipped, Michigan and Pennsylvania, are thought to lean more strongly toward Biden, leaving predominantly white, heavily rural Wisconsin as the most competitive. It could be the one state, if the election is close, that decides the November contest; polling suggests the former vice president holds a modest lead.

In a pre-coronavirus world, Democrats had hoped to bolster their claim to Wisconsin’s 10 electoral votes by staging their national convention in Milwaukee, a first for the brawny city on the western shore of Lake Michigan.

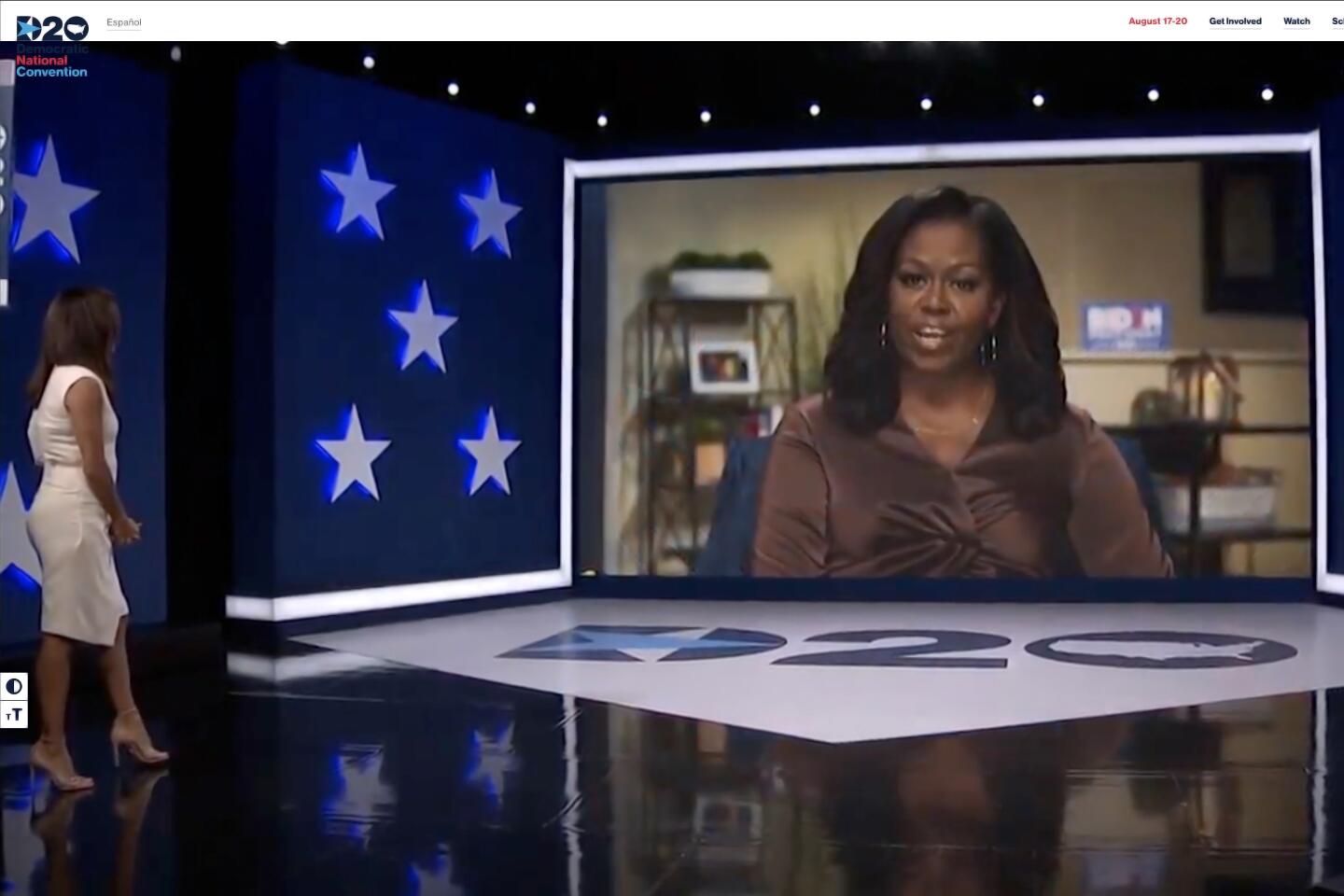

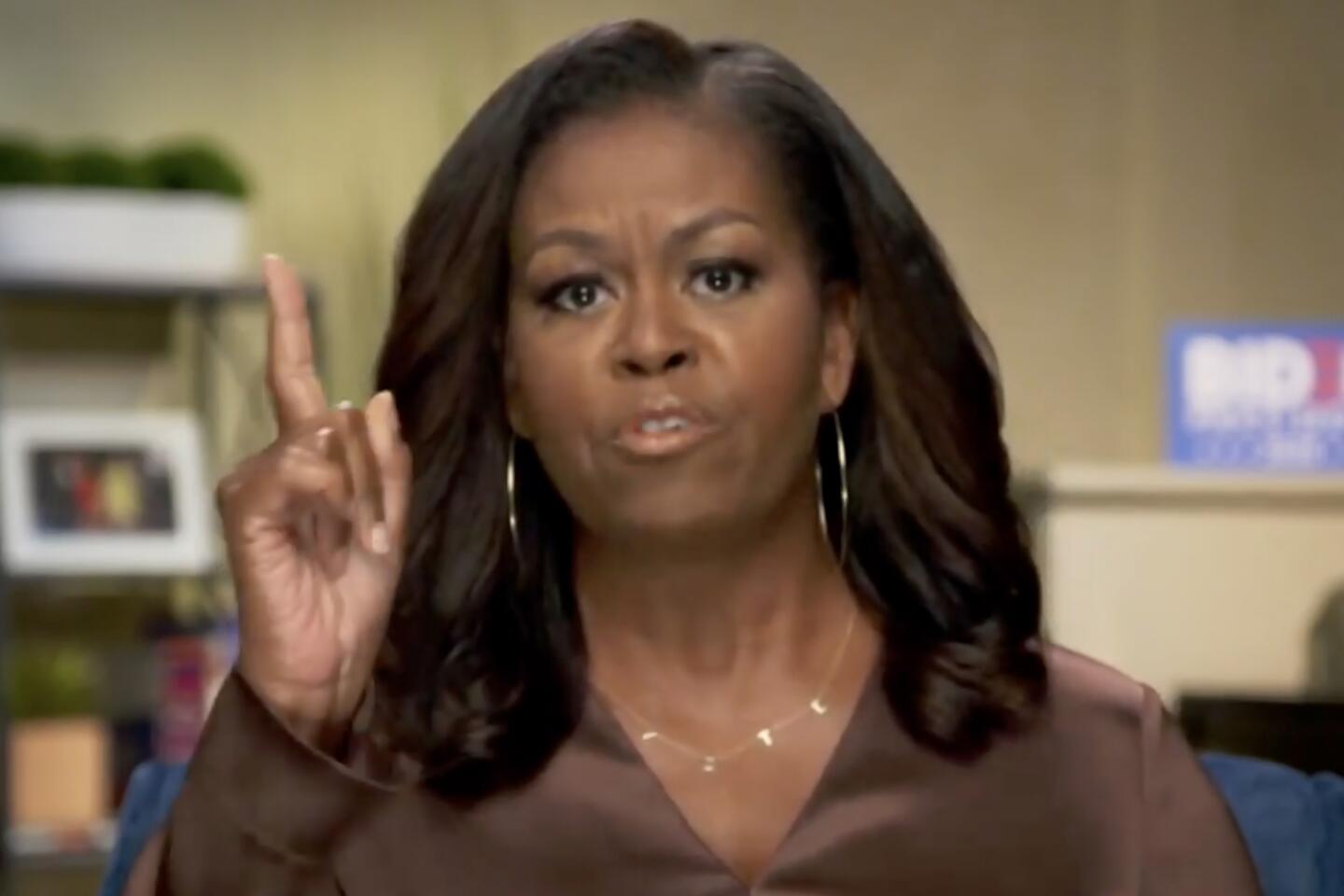

But the pandemic caused the party to delay, then shrink, then finally cancel the in-person gathering. While much of the technical production will be handled out of Milwaukee, the most important business — and whatever screen-sized pageantry the Democrats can muster — will be done remotely. Biden and Harris, once officially nominated, will deliver their acceptance speeches from Biden’s home state of Delaware.

Still, the presidential campaign here is no mere afterthought. Campaign signs dot Wisconsin’s farmland, suburban lawns and the lofts of the urban and trendy. The television airwaves have been ablaze for months with advertising, much of it scathingly negative: The candidates and their allies have already spent or reserved nearly $50 million worth of TV time, about evenly divided between the two sides.

“I’m pretty much done with the campaign,” Elena Phillips, a 59-year-old financial planner in suburban Milwaukee, said with a weary roll of eyes benumbed by so many political ads. “I can’t wait until November.”

She, too, is not particularly thrilled with Trump, though Phillips concedes she knew what she was getting personality-wise (loudness, coarseness) when she voted for him in 2016. Even so, the conservative-leaning independent considers the president a far better choice than Biden, who Phillips called “a career politician in office for way too many years with too little accomplishments.”

Pam Kuepper, 61, a first-grade teacher in Menasha, one of Wisconsin’s abundant small towns, offered a similar calculation. Trump may be “a little tacky,” she said, but she considers Biden at age 77 too old and too eager to spend other people’s money. (Trump is 74.)

“He’ll be, what, 82 when he finishes his term?” Kuepper said, her voice arcing incredulously at the thought of an octogenarian Biden in the Oval Office. “I’m sorry, but your mind isn’t as sharp as it was when you were 50 or 60.”

Four years ago, Trump carried Wisconsin by just over 22,000 votes out of nearly 3 million cast, becoming the first Republican to win the state in 32 years. The path to victory, like the candidate himself, was unique.

His performance lagged in areas where Republicans typically win by huge margins, in the conservative-leaning “WOW” counties — Washington, Ozaukee and Waukesha — that neighbor Milwaukee and lead to the vast countryside beyond.

Trump overcame that sluggish showing by walloping Democrat Hillary Clinton in Wisconsin’s small towns and rural areas, flipping 22 counties that voted for Barack Obama in his two big victories. (Clinton also suffered from a significant drop-off among younger and Black voters, particularly in Milwaukee.)

Since then, suburban support for the GOP has eroded even more, with Democrats gaining ground in the 2018 midterm election as well as a springtime Supreme Court election in which a liberal challenger knocked off one of the state’s conservative justices.

Perhaps more significant, a recent Marquette Law School poll found the president holding just a small lead over Biden in the rural areas where Trump swamped Clinton.

The survey also found concerns over COVID-19 growing and unhappiness with Trump’s handling of the crisis deepening as the number of cases in Wisconsin increased.

Neither candidate was particularly well-liked. Trump was viewed favorably by 42% of those surveyed and unfavorably by 55%. Biden was seen favorably by 43% and unfavorably by 48%.

But many seem ready to swallow hard in the service of winning in November.

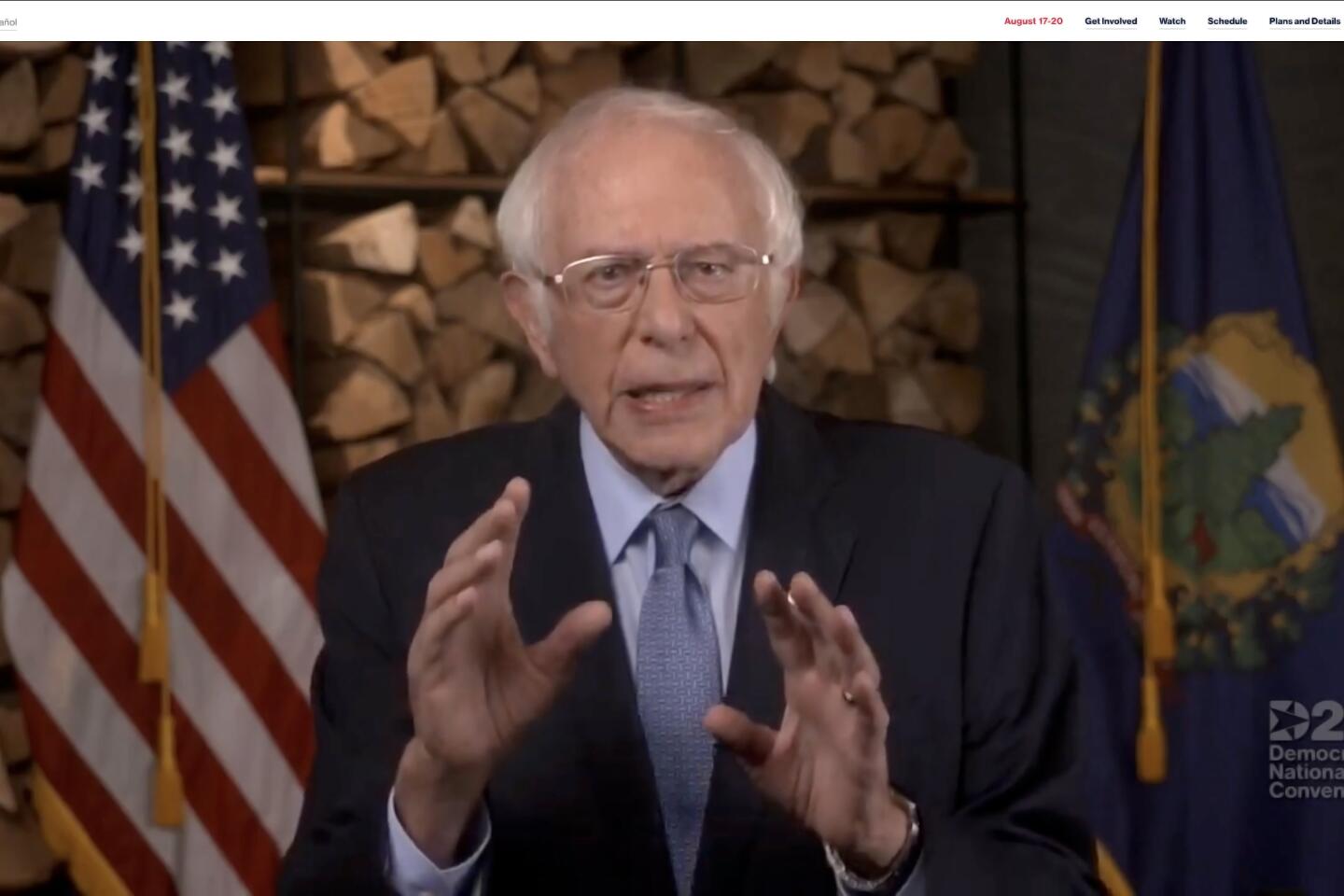

Rebecca Krueger, 37, a social worker in Green Bay, voted twice in Democratic primaries for Vermont Sen. Bernie Sanders and places herself well to the left of Biden. But she has no hesitation voting for him, especially now that Harris has joined the ticket. “Anything,” Krueger said, “is better for the country than Trump.”

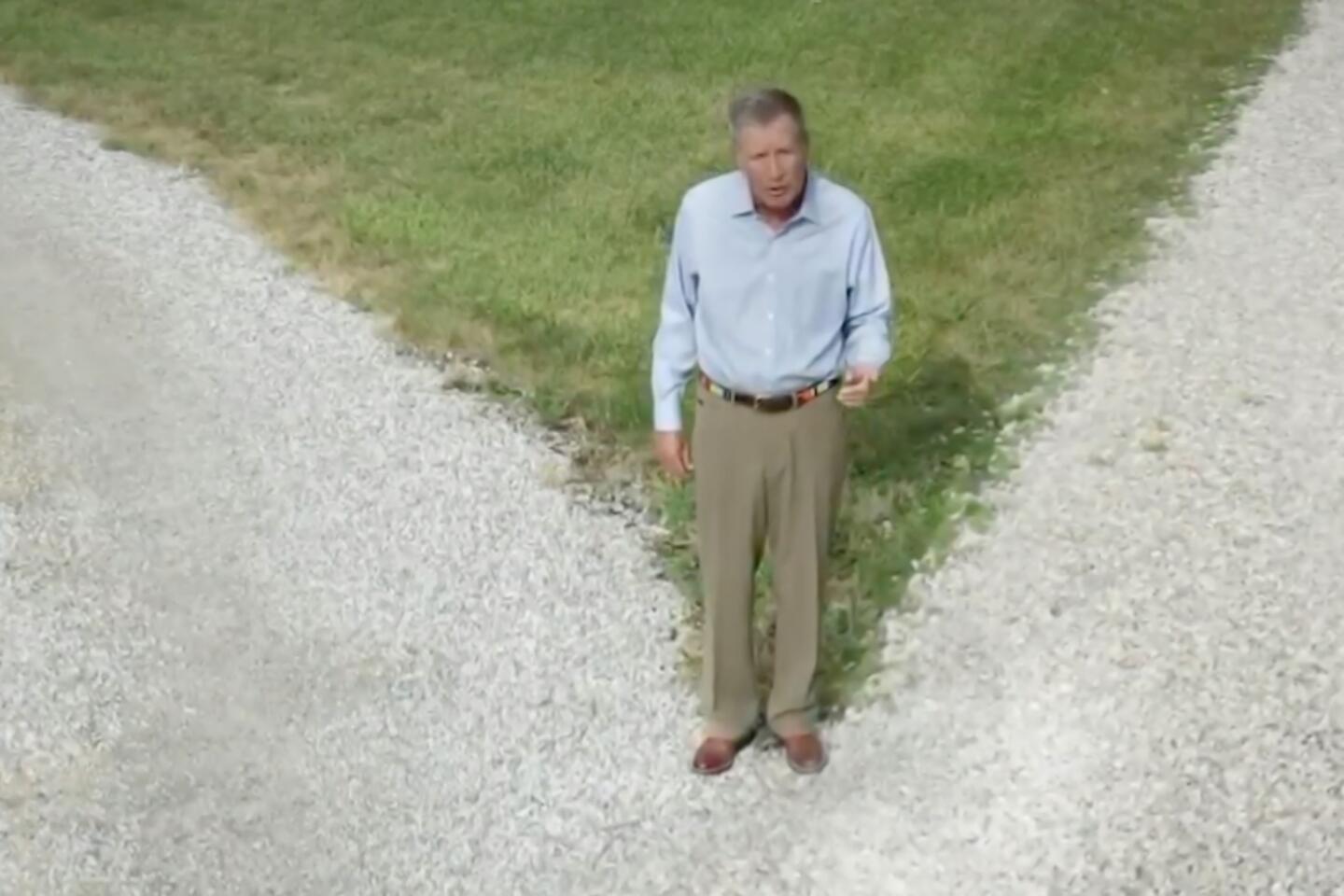

With partisans so deeply dug in, one key to the election will be independent voters like Murray in places such as Appleton, Oshkosh, Green Bay and other small industrial cities of the Fox River Valley, which, along with the WOW counties, are major battlegrounds.

The former police officer can’t bring himself to vote for Trump or Biden. So when he casts his ballot, he said, he will do so in support of Vice President Mike Pence or Harris, whose background as a prosecutor — San Francisco’s district attorney and California attorney general — appeals to Murray.

“I like Pence,” he said, pausing at the book drop outside Appleton’s downtown library. “But I want [Harris] to change my mind,” in part by convincing Murray that Democrats can better deal with the pandemic and bring an end to the country’s deep divisions.

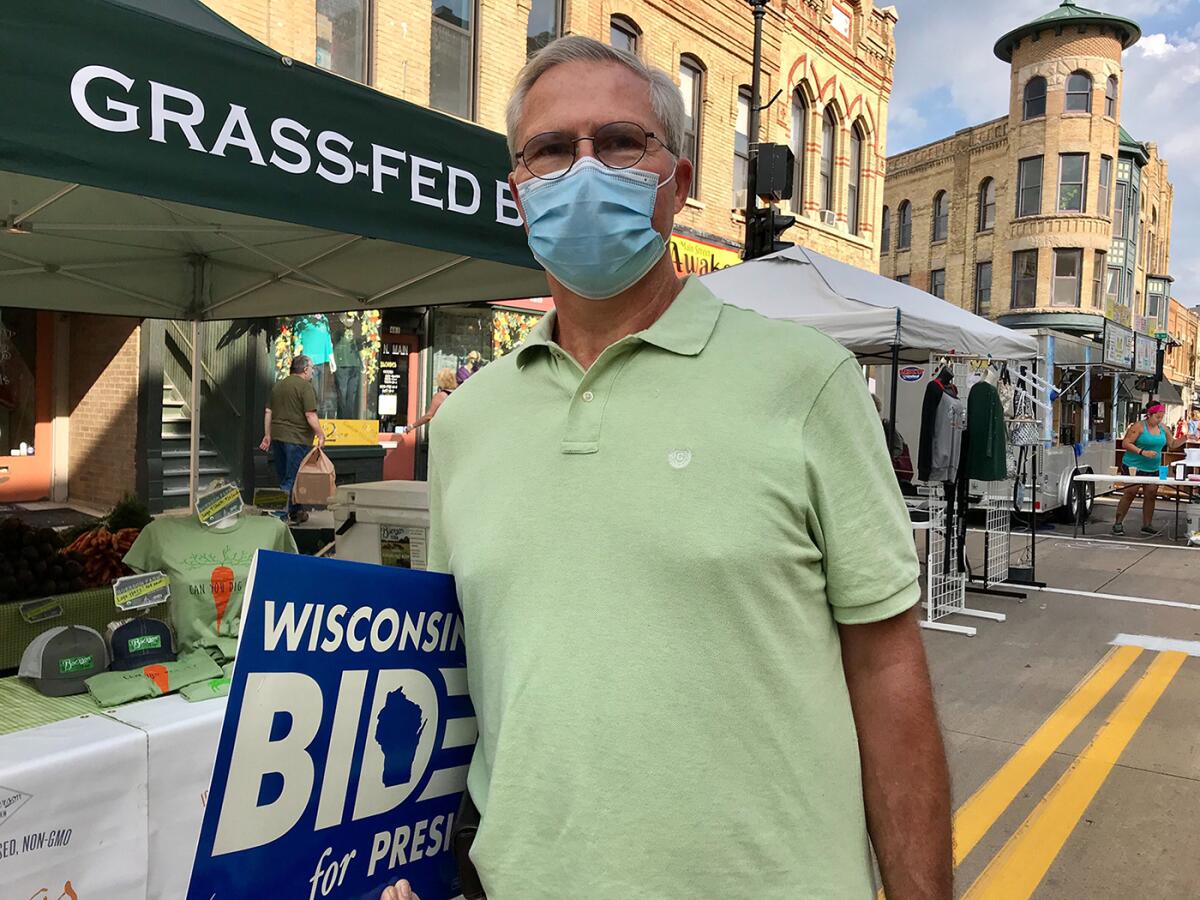

Doug Henke doesn’t need further convincing.

He couldn’t bring himself to vote for Trump four years ago, so he backed Clinton. This time, the lifelong independent is staking a Biden for president sign outside his Oshkosh home — an admittedly purposeful provocation in the Republican-leaning community.

The 64-year-old doctor has developed “an intense hatred” for the GOP, which he sees abetting Trump’s worst impulses, and hopes his small protest will lead to some spirited discussion with neighbors.

“I’m not trying to be partisan, I don’t really like that,” said Henke, who picked up the blue Biden sign along with some organic beets at the farmers market in Oshkosh. “But at some point you have to stand up and be counted. And in this election, this is what I feel like I have to do to accomplish that.”

One thing Biden hasn’t done is take Wisconsin for granted the way Clinton did.

The former secretary of State ran her first ad just a week before the election and became the first presidential candidate in nearly half a century — since Richard Nixon in 1972 — to not once set foot in Wisconsin.

Although Biden has not campaigned in person this year, he has conducted a number of interviews with local TV stations, participated in a remote discussion of rural issues and stocked his campaign with political professionals who helped elect the state’s Democratic governor, Tony Evers, and reelect its Democratic senator, Tammy Baldwin.

Still, Republicans consider the decision to cancel the convention a huge blunder. To underscore the point, Trump plans to hold an airport rally Monday in Oshkosh and Pence has scheduled a visit Wednesday to Darien, a rural speck in the southern part of the state.

“There’s a long track record of people in Wisconsin wanting to be able to meet, touch, feel and talk to their public officials,” said Brian Reisinger, a Republican strategist and former aide to two-term GOP Gov. Scott Walker. “Joe Biden apparently still hasn’t gotten the message that it cost his party the presidency in 2016.”

The campaign responded through Baldwin, a leading campaign surrogate. Biden “is prioritizing the health and safety of Wisconsinites,” the senator said. “The campaign has invested significant resources in the Badger State and shows no sign of slowing down.”

Wisconsin is one of the most evenly divided states in the country, evidenced over the last two decades by several exceeding close elections. (Obama’s twin victories were notable exceptions.) A blowout by either candidate in November would be a surprise.

For now, even Republicans concede that Trump — facing a raging pandemic, sputtering economy and flaring racial tensions — is in trouble. But backers like Tom Winkels take heart in 2016, when polls showed him trailing Clinton right up to election day.

“The polls are fake,” said Winkels, 66, the facilities manager at a Christian school in Oshkosh. “There’s just a lot of people who, because of the way the left treats Trump supporters, won’t say they’re Trump supporters even though they really are.”

He strolled through the farmers market, past rows of heirloom tomatoes and jars of locally produced honey, wearing a “Make America great again” T-shirt and flush with confidence. History, Winkels is certain, will repeat itself in November.