For a girl from Berkeley, about 5 years old, the setting must have been intoxicating: a bungalow surrounded by greenery in a newly independent African capital, where children ran outside to wave at the president’s car as he drove past.

This was where a young Kamala Harris spent time in the late 1960s, at a house in Lusaka, Zambia, that belonged to her maternal grandfather, an Indian civil servant on assignment in an era of postcolonial ferment.

The Indian government had dispatched P.V. Gopalan to help Zambia manage an influx of refugees from Rhodesia — the former name of Zimbabwe — which had just declared independence from Britain. It was the capstone of a four-decade career that began when Gopalan joined government service fresh out of college in the 1930s, in the final years of British rule in India.

It was also the start of a relationship that would define Harris’ life. Until his death in 1998, Gopalan remained from thousands of miles away a pen pal and guiding influence — accomplished, civic-minded, doting, playful — who helped kindle Harris’ interest in public service.

“My grandfather was really one of my favorite people in my world,” Harris, California’s junior U.S. senator, said in a recent interview.

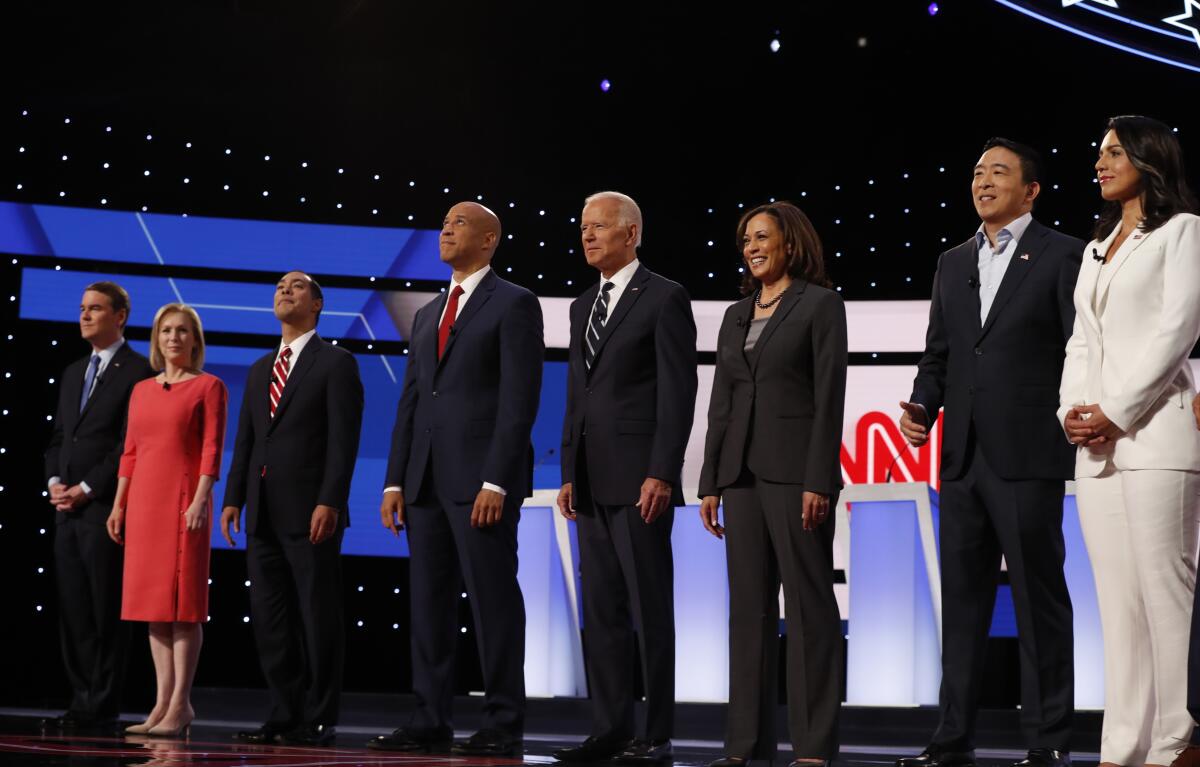

As she campaigns for the Democratic presidential nomination, Harris often invokes her late mother, Shyamala, a diminutive and dauntless breast cancer researcher who taught Kamala and her younger sister, Maya, to strive for excellence and lift others up.

These were principles Shyamala inherited from Gopalan and her mother, Rajam. In 1958, she surprised them by applying for a master’s program at UC Berkeley, a campus they had never heard of.

She was 19, the eldest of their four children, and had never set foot outside India. Her parents dug into Gopalan’s retirement savings to pay her tuition and living costs for the first year.

“It was a big deal,” said Harris’ uncle G. Balachandran, a 79-year-old academic in New Delhi. “At that time, the number of unmarried Indian women who had gone to the States for graduate studies — it was probably in the low double digits. But my father was quite open. He said, ‘If you get admission, you go.’”

It sounds today like a classic immigrant tale, but Harris’ grandparents’ broad-minded values were uncommon for the India of that time. That family legacy doesn’t shine through in Harris’ speeches on the campaign trail, where she has struggled to break into the top tier. She seldom delves into her Indian heritage, reflecting a broader reticence to share personal stories beyond a handful of well-worn anecdotes.

“Shyamala was quite definitely influenced by my father, and she in turn had a great influence on Kamala,” Balachandran said in a lengthy conversation in his home, a modest, semidetached apartment his father built on land he was given upon retirement. Much of the family’s story was related by Balachandran and his daughter. Other family members declined to be interviewed.

Gopalan was a Brahmin, part of a privileged elite in Hinduism’s ancient caste hierarchy. In post-independence India, convention destined Brahmin offspring for arranged marriages and comfortable careers in academia, government service or the priesthood — if they were men. Women were not expected to work at all.

All four of his children bucked convention in their own ways.

Balachandran, who earned a PhD in economics and computer science from the University of Wisconsin and enjoyed a distinguished academic career in India, married a Mexican woman and had a daughter. His younger sister Sarala, a retired obstetrician who lives outside the coastal city of Chennai, never married. The youngest, Mahalakshmi, an information scientist who worked for the government in Ontario, Canada, had an arranged marriage but bore no children.

“Not one of them was traditional,” said Harris, who grew close to her aunts and uncle during extended visits to India as a girl.

“When you’re raised in a family, I guess later in life you realize how your family might be different,” she said. “But it all seemed very normal to me. … I obviously did realize as an adult, and as I got older, that they were extremely progressive.”

::

Gopalan was born in 1911 in Painganadu, a village ringed by temples about 180 miles south of Chennai, then known as Madras. His marriage to Rajam, who was raised in a nearby district of Tamil Nadu state, was arranged.

He started out as a stenographer, and moved the family from New Delhi to Mumbai to Kolkata as he climbed the ranks of the civil service.

In her 2019 memoir, “The Truths We Hold,” Harris wrote that Gopalan had been part of India’s independence movement, but family members said there was no record of him having been anything other than a diligent civil servant. Had he openly advocated ending British rule, he would have been fired, Balachandran said.

Raised mainly by Rajam — a no-nonsense woman with a soft spot for stray animals — the children were studious but occasionally got into mischief. Shyamala and Balachandran, whom the family calls Balu, were about two years apart and partners in high jinks. They would hide under beds, prompting Rajam to root them out with a broom handle.

In 1950s Mumbai, then known as Bombay, where Gopalan was posted as a senior commercial officer at India’s busiest trading hub, there were clear rules at home: To thwart businessmen who wanted to offer bribes, no strangers were allowed to enter the family residence on Pedder Road in the heart of the city, and the children were not to accept any deliveries.

But when visitors arrived bearing parcels, Shyamala and Balachandran would sometimes peek inside.

“If it was sweets or fruits, we’d say, ‘OK, you can give it,’” Balachandran said.

Shyamala was a gifted singer, specializing in the classical Carnatic music of southern India, a discipline she learned from her mother. She won a gold medal in a national competition and occasionally sang on the radio, earning a small bit of cash.

And unlike many Indian parents back then, Balachandran recalled, they let Shyamala keep the money.

::

At Lady Irwin College, then one of the top women’s institutions in New Delhi, Shyamala studied home science, which encompassed nutrition, textiles and childhood development. It mainly trained students for lives as homemakers, and her father seemed to think the subject was beneath her.

“What is home science?” Balachandran remembered him needling her. “Are you learning how to invite guests?”

Rajam, who was active in raising funds for social causes, was determined that the children pursue careers in medicine, engineering or the law.

“My grandparents had really high expectations of their kids and were nurturing,” said Balachandran’s daughter, Sharada Balachandran Orihuela, an associate professor of English and comparative literature at the University of Maryland.

“I do think now of just how permissive they were in allowing their daughters to leave them, but also of how bold the daughters were to want to leave to begin with,” she said. “And given that Shyamala was the oldest, she really set the stage for the rest of the siblings to follow in her path.”

When Shyamala left to study nutrition and endocrinology at Berkeley, eventually earning a PhD, most Indian households didn’t have phone lines. The family stayed in touch through letters, handwritten on lightweight, pale-blue stationery known as aerograms that took about two weeks to travel between India and California.

At the American library in New Delhi, Gopalan found an atlas with a street map of Berkeley. He looked up Shyamala’s address and traced her commute to campus. On her first trip home, Shyamala brought happy souvenirs of her new American life: vinyl jazz records by Louis Armstrong and Dave Brubeck.

Covering Kamala Harris

She joined the black civil rights movement, where she met a brilliant Jamaican economics student named Donald Harris. When she and Harris married in 1963 — in what in India is still described as a “love marriage” — it marked an even greater challenge to convention, especially because she didn’t introduce him to her parents beforehand.

Donald Harris’ race wasn’t an issue for Shyamala’s parents, Balachandran said, but “the fact that she didn’t marry in India might have upset them, and the fact that it was someone they didn’t meet.”

No one from the family attended the wedding, but Balachandran said that was because of financial reasons. He had just gone off to study in Britain, and money at home was tight.

A few years later, Shyamala and Donald brought their daughters to Zambia. Kamala would have been 4 or 5 years old; Maya, two years younger, was still sleeping in a crib. The young Kamala was oblivious to the intrigue swirling around her, with Gopalan’s government-issued car whisking him to meetings with Zambian officials and diplomats dropping by for visits.

What she remembers is the soil of Lusaka, rich with copper, which glowed a fiery red.

::

After Shyamala divorced Donald in the early 1970s, she brought her daughters back to India often, usually to Chennai, where her parents settled after Gopalan retired. As the eldest grandchild, Kamala sometimes tagged along on Gopalan’s walks with his retiree buddies, soaking up their debates about building democracy and fighting corruption in India.

“My grandfather felt very strongly about the importance of defending civil rights and fighting for equality and integrity,” Harris said. “I just remember them always talking about the people who were corrupt versus the people who were real servants.”

In photos, Gopalan stares gravely from behind oversized glasses, but with his granddaughters he cracked sly jokes. When Rajam left the house, Gopalan, a strict vegetarian who avoided even eggs, sometimes cast Harris and her sister a conspiratorial look and said: “OK, let’s have French toast.”

He taught Harris to play five-card stud poker. If she misbehaved, Gopalan would take her into another room and pretend to slap her on the hand — urging her to shriek in mock pain — before reemerging to tell Shyamala, “I handled it.”

Harris wore saris for family events and spoke a few Tamil phrases with her relatives. Shyamala was determined that the girls retain links to India even as she understood — as Harris wrote in her memoir — “that she was raising two black daughters” in an America that would see them as black.

“There was never a question that they were Indian,” said Balachandran Orihuela, 36. “I don’t think she felt conflicted about it. She told the girls, ‘You are Indian; you are black. You don’t have to prove that you’re one or the other.’”

Shyamala bore the hidden scars of discrimination — Harris has said she was passed over for promotions and dismissed as unintelligent because of her accent — and dispensed lessons to her family and graduate students of color with the same sharp, sassy wit.

Her toughness became well known. After she had back surgery, she would work from the bedroom of her spacious condo overlooking Lake Merritt in Oakland, sitting up on her adjustable Tempur-Pedic mattress amid a sea of papers.

Balachandran Orihuela, who lived with Shyamala as an undergraduate at Oakland’s Mills College, recalled extended conversations surrounding race following the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks. Shyamala warned her that American men would call her exotic, a term she said was meant to diminish her.

“The minute they call you exotic, you walk away from them and tell them to f— off,” Balachandran Orihuela remembered her saying. If anyone asked where she was from, Shyamala admonished her to answer: “None of your business.”

Shyamala died in 2009 of complications from colon cancer. She was 70. Rajam passed away later that year.

In her cousin Harris, 18 years her senior, Balachandran Orihuela sees glimmers of her aunt’s intensity and focus, as well as her warmth. When Harris arches an eyebrow during a presidential debate, the feisty skepticism reminds her of Shyamala.

“There’s very little ambiguity, very little moral relativism to debate with Kamala,” she said, “and Shyamala was very similar.”

::

In February 1998 — the month Harris was appointed assistant district attorney in San Francisco, beginning her political rise — she traveled to India to visit Gopalan, who was 86 and ailing.

Two weeks after her visit, he passed away.

One of Harris’ fondest memories of Gopalan’s final years was in 1991, when the whole family gathered in Chennai to celebrate his 80th birthday. It had been at least 20 years since everyone was together, and Rajam — by then great-grandmother to Maya’s daughter, Meena — insisted that they all stay in their three-bedroom apartment, on a quiet, tree-lined street a few blocks from the beach.

Overwhelmed with pride at having four generations under her roof, Rajam urged them not to venture outside in one group, lest the evil eye fall on her extended brood, Balachandran recalled.

Harris, who was about 27 at the time, remembered a house bristling with strong personalities, her aunts and uncle suddenly reverting to the role of children. Rajam quibbled with Shyamala, two forces of nature colliding in the ground-floor flat.

“It was just a whole scene,” Harris said with a laugh, “and by the end of it we went to a hotel.”

Bengali reported from New Delhi and Mason from Los Angeles.