Hunkered over a Xerox machine at an ad agency above a flower shop on Melrose Avenue, Daniel Ellsberg began the laborious process of photocopying the smuggled documents that he hoped would end the Vietnam War.

Earlier that day in Octobert 1969, he had opened the safe in his office at Rand in Santa Monica, where he worked as an analyst, and removed the first batch of top-secret papers. He had walked past the lobby guards with his briefcase, waving casually.

“I took it for granted that what I was doing violated some law,” Ellsberg wrote in his 2002 book “Secrets: A Memoir of Vietnam and the Pentagon Papers.”

In this series, Christopher Goffard revisits old crimes in Los Angeles and beyond, from the famous to the forgotten, the consequential to the obscure, diving into archives and the memories of those who were there.

His conscience had been eating him for years. He had been a Marine, a dedicated Cold Warrior and a Pentagon consultant advising the architects of the Vietnam War, accepting the premise that it might thwart a Stalinist dictatorship and promote democracy.

At 38, he had become disillusioned with what he called a “hopeless and interminable” war, one built — as he hoped the public would grasp from the papers — on decades of lies.

There were 47 volumes, consisting of 7,000 pages documenting American military decisions across two decades. They showed that optimistic speeches about the war masked much grimmer behind-the-scenes assessments, and that keeping American presidents from the stigma of humiliating defeat was a dominant aim of continuing the war.

The papers showed “repetitive patterns of internal pessimism and of desperate escalation and deception of the public in the face of what was, realistically, hopeless stalemate,” as Ellsberg put it in his book.

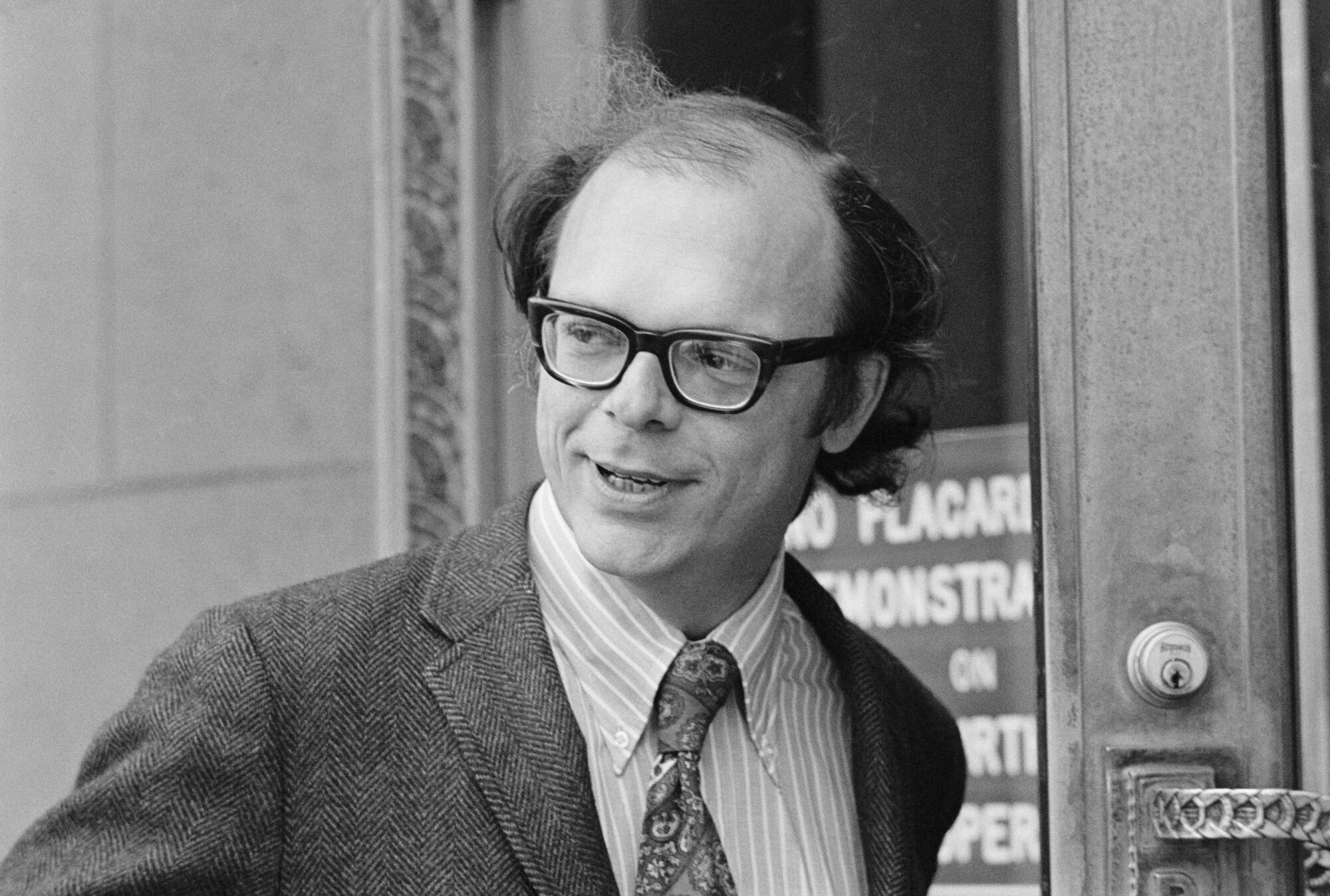

A former Rand colleague, Anthony Russo, had encouraged Ellsberg to leak the papers to the media. Russo’s girlfriend ran an ad agency and offered the use of her Xerox machine.

Ellsberg made copies after hours, sometimes bringing his 13-year-old son to help. If the government locked him up, as seemed plausible, he would be unable to support his kids. But he viewed the stakes as “larger than me, or even my own family.”

Ellsberg slipped the papers to the New York Times, which began publishing them in June 1971. Other newspapers followed, despite fury from the Nixon administration, and the U.S. Supreme Court decision affirming the media’s right to publish became a 1st Amendment landmark. Steven Spielberg made a movie about it.

Less remembered was the criminal prosecution that followed in Los Angeles.

The panic engulfing the Nixon White House — and its loathing for Ellsberg — would be captured in Oval Office tapes. To the president’s advisers, Ellsberg was a traitor responsible for “an attack on the whole integrity of government” and “a devastating security breach of the greatest magnitude.”

Enraged to see Ellsberg portrayed as a national hero, Nixon vowed to destroy him, declaring: “We’ve got to get this son of a bitch.”

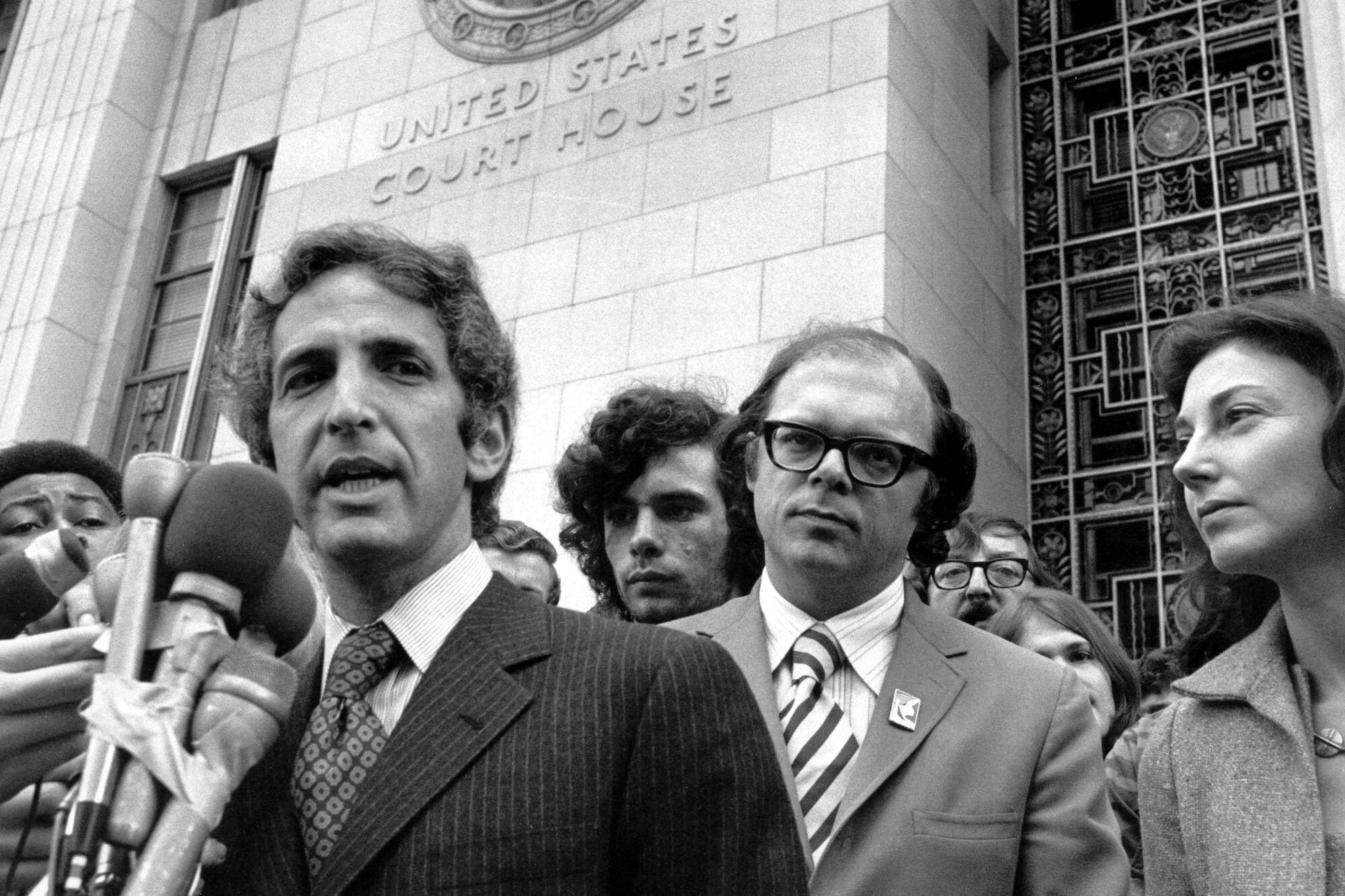

The Justice Department indicted Ellsberg under the Espionage Act, and he faced a possible 115 years in prison if convicted of conspiracy, espionage and theft of government property.

When he and co-defendant Russo went on trial in downtown Los Angeles in 1972, the questions were large: Had the disclosures jeopardized national security? Were there circumstances in which the government’s zeal for secrecy could be overridden in the public interest?

Mark Rosenbaum was a Harvard Law School student when he took a leave of absence to assist the defense team.

“This is, to my knowledge, the first trial in the history of the country that really examined the manner in which the government lied to its people,” Rosenbaum, a longtime public interest attorney in Los Angeles, recently told The Times. “Most people took what the government said as the truth. This trial blew that open. In 2024, it’s hard to remember how radical and revelatory that was.”

On trial was not just American foreign policy but “the whole system for classifying documents,” Rosenbaum said. “We showed that what was classified as secret or top secret was really an attempt to [suppress] politically embarrassing material.”

The defense team believed that Nixon’s DOJ wanted the trial to take place on the West Coast in hopes of finding favorable jurors from the aerospace industry, which was heavily dependent on the Defense Department. Rosenbaum recalled that the jury was picked from “a lot of retired government employees” who seemed hellbent on conviction.

“You could feel the bad vibes,” he said.

But appellate arguments caused a months-long delay, and a new jury was picked that seemed friendlier to Ellsberg’s side.

There was little disagreement on the facts. No one disputed that Ellsberg had taken the papers and photocopied them. But the defense argued that the disclosure did not imperil national defense, that the documents dealt with past presidential administrations, and that much of the material had been in the public domain anyway, albeit in scattered form. And before giving the papers to reporters, Ellsberg had tried unsuccessfully to make them public by slipping them to members of Congress.

But Congress was in the “grip of a stranglehold by the executive branch,” defense attorney Charles Nesson told the judge, adding: “There was no way other than the one defendants chose.”

In a recent interview with The Times, Nesson, now 85, said another thrust of the defense was that Ellsberg had not actually stolen government property. He had photocopied documents and returned the originals. What he had done was divulge information — but “the government doesn’t own information.”

In late April 1973, deep into the trial, U.S. District Judge Matt Byrne handed Ellsberg’s attorneys startling reports he had received from the Justice Department. The White House-directed team of operatives known as “the plumbers” had broken into the Beverly Hills office of Ellsberg’s psychiatrist, looking for compromising material.

Late one night, Rosenbaum said, he and another young attorney drove to the small East Los Angeles home of a woman who had cleaned the psychiatrist’s office and seen the burglars. The lawyers had an issue of Time magazine featuring a photo of Watergate conspirator G. Gordon Liddy. The cleaning lady identified him as one of the burglars, Rosenbaum said.

“That began to break things open,” Rosenbaum said.

If you have information on old crimes, famous, once-famous or obscure, contact [email protected]

In another revelation damning to the government, the FBI admitted it had captured Ellsberg’s voice on wiretap surveillance years earlier — and that the transcripts had vanished.

But what finally derailed the case was the Nixon administration’s unseemly overtures to the judge. The defense team learned that Judge Byrne had visited the president’s San Clemente home mid-trial, and that Nixon had offered him the job of running the FBI.

It amounted to Nixon “trying to bribe the judge to somehow get a conviction,” Nesson said. It was “a kind of capstone to the misbehavior that Ellsberg was disclosing.”

The judge acknowledged the San Clemente meeting but said he rejected the FBI job. Shortly afterward, Nesson said, he got a call that the judge had been spotted in a park with Nixon aide John Ehrlichman.

“I knew that was a killer,” Nesson said. “The judge was finally cornered.”

Defense lawyers debated whether to spring the information on the judge in court or inform him privately. Nesson opted to call his chambers.

“I’ve never really regretted the professional courtesy involved in putting him on notice that he was about to get killed, effectively,” Nesson said.

In May 1973, Byrne declared a mistrial and dismissed all charges against Ellsberg and Russo on the basis of government misconduct, saying: “The bizarre events have incurably infected the prosecution of this case.”

Jurors came by the office that defense attorneys had established in downtown L.A. It was clear that many had been in favor of acquittal.

The leaked papers and the resulting trial fueled a distrust and cynicism about government that only intensified as the Watergate scandal played out.

Did Ellsberg’s leak help end the war? As Ellsberg argued in his book, fighting the Watergate scandal prevented Nixon from blocking a congressional resolution to halt bombing. And Nixon’s attempt to cover up the criminal capers of White House operatives — such as the break-in at the office of Ellsberg’s psychiatrist — would figure largely in his disgrace and resignation.

With stricter laws about the release of government secrets, Rosenbaum said the Ellsberg defense would stand little chance in court today.

“Today it would be open and shut” in favor of the government, Rosenbaum said, since now “the sole burden on the government is to prove the document is classified, and that’s the end of it. ‘Was the document classified?’ ‘Yes.’ Done.”