In France, a visit to the doctor typically costs the equivalent of $1.12.

A night in a German hospital costs a patient roughly $11.

And in the Netherlands — one of the few wealthy nations other than the U.S. where patients face a deductible — insurers usually must cover all medical care after the first 385 euros, roughly $431.

Healthcare in the U.S. has long been unique. But few things so starkly set the American system apart as how much patients pay out of pocket for medical care, even if they have insurance.

“The U.S. likes to see itself on par with other high-income countries,” said Jonathan Cylus, a former economist at the Department of Health and Human Services who now studies patient costs internationally at the World Health Organization and European Observatory in London. “The truth is, it’s a real outlier.”

Nearly all of America’s global competitors — whether they have government health plans, such as Britain and Canada, or rely on private insurers, such as Germany and the Netherlands — strictly limit out-of-pocket costs.

So while tens of millions of insured Americans must balance medical bills with spending on food and other basic needs, such trade-offs are largely unthinkable for patients in Western Europe, Japan and Australia, a Times examination of international health insurance systems shows.

“We only have to worry about getting well,” said Pieter Piers, a 57-year-old Dutch engineer who was talking with his family doctor earlier this year about work-related stress in Gorinchem, a walled city in the table-flat farmland of southern Netherlands.

“If I had to worry about how to pay for it all, I don’t think that would be very helpful for getting better,” said Piers, one of dozens of patients and physicians worldwide interviewed for this story, including at clinics and hospitals in Germany, Britain and the Netherlands.

The Netherlands, like many wealthy countries, mandates that visits with primary care doctors are free so patients won’t be discouraged from seeking care.

By contrast, as deductibles in job-based health plans in the U.S. have more than tripled in the last decade, half of Americans who have coverage through an employer say they or close family members have put off going to the doctor or filling a prescription because of cost in the last year, according to a nationwide survey conducted for this project by The Times and the nonprofit Kaiser Family Foundation.

One in six covered workers has had to make a difficult sacrifice in the previous year, including taking on extra work or cutting back on food, clothing or other essentials, the poll found.

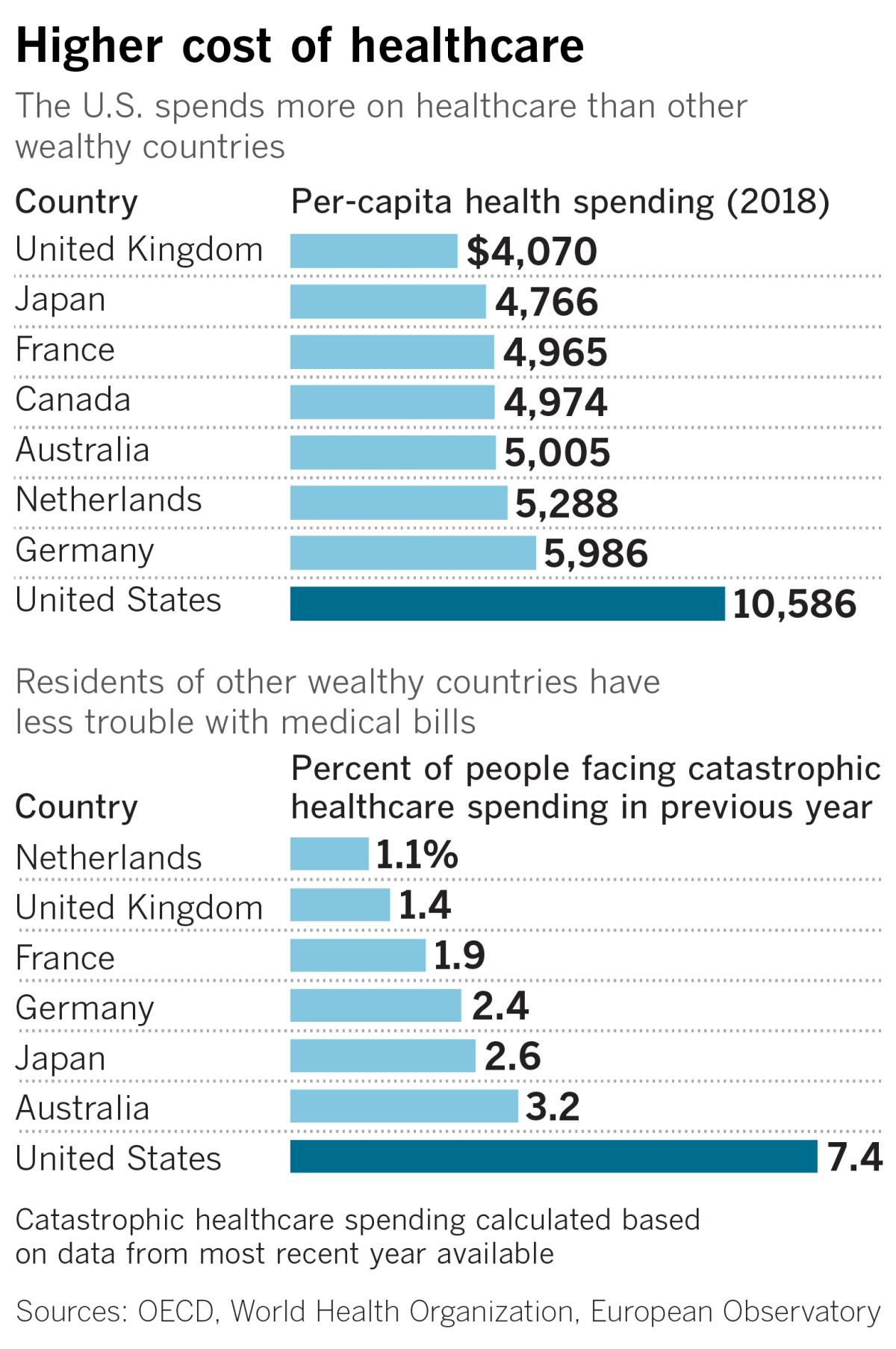

In the Netherlands, just 1 in 90 households faces catastrophic health spending that competes with necessities such as food and housing, a recent World Health Organization analysis of patient spending in three dozen countries found.

In Ireland, Great Britain, Sweden, France, Germany and Japan, fewer than 1 in 35 households had medical bills that threatened their financial security.

The financial struggles of American patients have prompted renewed calls by some Democrats for a government-run, single-payer system, or “Medicare for all,” as it is sometimes called.

But the experiences of other wealthy nations suggest that strict limits on how much patients must pay and tight regulation of prices are more consequential than whether health coverage is provided directly by the government or through private insurers.

“There isn’t one system that works,” said Thomas Rice, a UCLA health economist who is writing a textbook about health insurance systems around the world. “Lots of different kinds of systems can protect patients from high costs.”

In the United Kingdom, care “free at the point of service” was a founding principle of the National Health Service when it was established after World War II to give Britons affordable healthcare “in place of fear,” as health minister Aneurin Bevan explained at the time.

Patients in the National Health Service usually face no medical bills when they go to the doctor or hospital. Co-pays for prescription drugs are capped at the equivalent of about $12, no matter how expensive the medication.

All hospital care in Australia is similarly covered at no cost for patients, who are protected by a government health plan known there as Medicare. The same is true in Canada.

In Germany, which relies on regulated private health plans, all physician visits are free for patients. Medication co-pays are capped at 10 euros, or about $11.

And Dutch primary care visits have long been cost-free, despite the deductibles for other medical services.

“A very important value in the Netherlands is equity,” said Dr. Jako Burgers, a family physician in Gorinchem who also helps develop clinical guidelines for the Dutch system. “We don’t want a system that benefits the rich more than the poor.”

In the U.S., health insurers can require patients in an individual plan to pay up to $7,900 out of their own pockets before care is covered in full. One in four workers has a deductible of $2,000 or more, according to an annual Kaiser Family Foundation survey.

That kind of cost-sharing would never be tolerated in Germany, said Dr. Markus Frick, a senior official at that country’s leading pharmaceutical industry group, the VfA. “If any German politician proposed high deductibles, he or she would be run out of town,” Frick said.

In Australia, a recent proposal to establish the equivalent of a $5 co-pay for primary care visits fueled such an outcry that the federal government was forced to withdraw the idea.

And in the Netherlands, the government is under mounting pressure to reduce deductibles, which many there believe are too high.

In the U.S., health plans with lower deductibles typically have much higher premiums.

But other wealthy nations, in addition to limiting patients’ out-of-pocket costs, also strictly control the cost of health insurance.

Residents of many countries — including Britain, Australia and Canada — pay no premiums because basic health insurance is financed through taxes, though residents can buy supplemental coverage on their own. In Germany and Japan, a set percentage of workers’ wages is deducted for health insurance, making premiums less expensive for lower-wage workers.

“I don’t think about any costs,” Dorota Langner, a German massage therapist who had pancreatic cancer, said after meeting with her oncologist at a hospital in Berlin earlier this year.

Langner, 41, a single mother, had other worries, including what would happen to her two teenage children. “I don’t know what I’d do if I also had to think about what this would cost me,” she said.

Langner died a few months later.

Keeping insurance premiums and medical bills in check has helped keep overall healthcare spending far lower in most wealthy countries than in the U.S.

Last year, for example, America’s total healthcare tab, including spending on government programs, private health insurance and patients’ out-of-pocket costs, exceeded $10,000 per person, according to government data. That was more than twice what governments, insurers and patients in the Netherlands, Canada, France and the United Kingdom spent and almost twice Germany’s tab.

Controlling costs has sometimes required trade-offs.

Hospitals in Britain, for example, can be overcrowded and in need of renovation. In some, patients must share a room with six or more other patients.

In Canada, patients can face substantial delays for care, with 18% reporting having to wait four months or longer for an elective, nonemergency surgery, compared with just 4% in the U.S., according to a recent international survey conducted by the Commonwealth Fund, a New York-based foundation that studies international health systems.

Evidence suggests that some medical care in the U.S., particularly in hospitals, may be better, as well.

For example, American patients are less likely to die after being hospitalized following a heart attack than are those in most wealthy countries, data show.

However, Australia and Sweden top the U.S. on this measure of cardiac care. Wait times in Germany or France are shorter than in the U.S.

And measures of the overall quality of healthcare place the U.S. near the bottom. Americans are far more likely to die prematurely from diseases that could be treated with timely, high-quality care, such as diabetes, childhood measles and some cancers.

The death rate from these avoidable conditions is more than 30% higher in America than in the United Kingdom and Germany, and nearly twice as high as in Australia, France and Norway, according to an analysis by the European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies, a partnership of international health researchers.

Beyond better health outcomes, residents of most other wealthy countries simply enjoy more peace of mind.

In south London, Chris and Afii Marshall, who had taken their 2-year-old daughter to the emergency room at King’s College Hospital after she cut her lip playing, shuddered at the thought of what they might pay in the U.S.

“I’ve heard stories. It’s terrifying,” said Chris Marshall, noting that he’s had many retail jobs that in America would likely come with high-deductible coverage. “I’d be very, very worried.”

The Marshalls faced no bills for their visit in Britain.

The United Kingdom — like most wealthy nations — keeps patients’ costs in check by tightly regulating the prices that doctors, hospitals and drug companies can charge.

Government regulation of prices has been done for decades in the U.S. by Medicare, which has a fee schedule for most physician and hospital services.

However, this kind of price regulation is rare in commercial health insurance, where most working Americans get coverage.

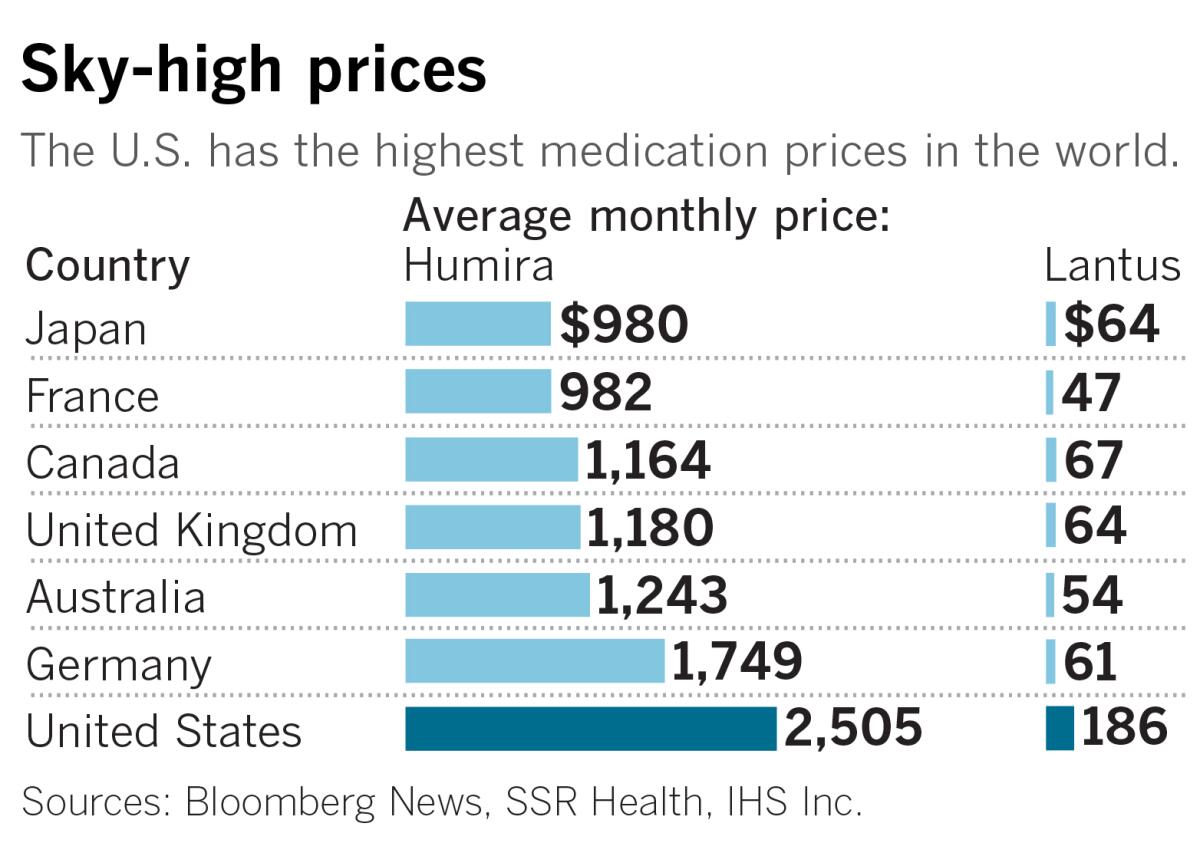

Instead, individual insurance companies negotiate prices with hospitals and physicians and drug makers. Under this system, prices for medical services and prescription drugs in the U.S. far outpace prices in other countries.

A month’s supply of the popular arthritis drug Humira, for example, tops $2,505 on average in the U.S., according to a 2015 analysis by Bloomberg News and research firms SSR Health and IHS Inc.

In Britain, where the National Health Service sets prices, the drug costs $1,180. In Japan, the monthly price is just $980.

Physicians’ services and hospital care are also far pricier in the U.S., data show.

A knee replacement that costs more than $28,000 on average here costs about $18,000 in Britain and less than $16,000 in Australia, according to 2015 figures collected by the London-based International Federation of Health Plans.

The average price for heart bypass surgery tops $78,000 in the U.S. The same procedure costs less than $29,000 in Australia and $24,000 in Britain.

When medical and pharmaceutical prices are high, insurers pass the costs on to patients. That has fueled higher premiums and, in more recent years, skyrocketing deductibles.

“People may not make the connection, but what’s coming out of their pockets is the result of a failure to control prices,” said Dr. Eric Schneider, senior vice president of the Commonwealth Fund.

“What other countries have learned is that without some form of price regulation, there is no effective check on prices.”

Support for this story came from the Assn. of Health Care Journalists’ International Health Study Fellowship, funded by the Commonwealth Fund.