It was nearly dark outside when Blaire Van Valkenburgh strode through the woods, lanterns dangling from both hands, to visit the soil that was once her husband.

She walked easily through a tangle of roots and rocks to a small bowl-shaped glade just visible from her kitchen window on Orcas Island, Wash. She and her husband of 40 years, Robert Wayne, had planned to retire here. Then he was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer.

Towering Pacific madrone trees and Douglas fir appeared like ghostly shapes around the area where, months earlier, friends and family had emptied seven burlap bags that held Wayne’s mulch-like remains and raked them into a dry sprawling puddle under the trees.

This was the “burial” Wayne wanted, chosen just a few weeks before he died on Dec. 26, 2022, at their Calabasas home. The genetics pioneer loved hiking in the woods and was always first in line to try something new, “especially things that made sense from an environmental, Earth-friendly point of view,” said Van Valkenburgh, a paleobiologist at UCLA.

But this kind of burial — natural organic reduction — won’t be legal in California until 2027, so Van Valkenburgh paid to fly her husband’s body to Washington, the first state to legalize human composting in 2020. Three months later, two women in a Subaru drove to Orcas Island and unloaded the bags of Wayne’s soil from the back seat — about 250 pounds of what looked like a fine, odorless wood-chip mulch.

The area looks bare now, Van Valkenburgh said apologetically, but someday she’ll plant bulbs. In the awkward silence that followed, her grief was palatable, but then she suddenly threw back her head and stared up above the trees. “This is what he sees,” she said softly, gazing into a purple-black sky slowly freckling with stars.

Our last ‘toxic’ act

The American approach to death and burials has changed dramatically over the last century — from families putting loved ones in a simple box in the ground to expensive, elaborate funerals involving poisonous embalming chemicals, concrete or lead grave liners and land that’s increasingly hard to find in urban areas.

Over the last few decades, however, more Americans have chosen cremation — 61% in 2023 — for its ease and much lower cost. You can arrange for a direct cremation — one without a service or other trimmings — for under $1,000, compared with the country’s median burial costs of nearly $8,000 (not including cemetery fees for vaults and plots).

But cremation is also an environmental nightmare, requiring huge amounts of energy to incinerate bodies into a highly alkaline and salty ash detrimental to plants and soil in concentrated amounts. Plus, cremation gives off so much carbon dioxide that the South Coast Air Quality Management District limits the number that can be performed every month in California’s largest metropolitan region — caps it had to suspend in early 2021 when the death rate more than doubled due to COVID-19.

“The truth is, the last gesture most of us will make on this earth is toxic,” human composting pioneer Katrina Spade wrote in 2016, when she applied for a grant to investigate the feasibility of composting human bodies in the United States.

Now, with 60% of Americans saying they would prefer greener options for burial, we appear poised for another major shift, said Sarah Chavez, founder of the Death Positive movement, which advocates for “honest conversations” about death and dying.

“Over a hundred years ago, there was no funeral industry. People took care of their own dead,” Chavez said. We’ve outsourced that job over the years, to our detriment, she said, as though whisking a body away can somehow relieve our loss.

“[Human] composting really resonates with a growing number of people who see it as a way to give back to the earth; a way of making their final act a meaningful one and being part of a more unique, family-led funeral that will truly honor the lives of their persons, and who they truly were,” Chavez said.

In addition to Washington, nine states — Oregon, Vermont, Colorado, New York, Nevada, Arizona, Maryland, Delaware and California — have legalized natural organic reduction and at least 12 others have introduced bills.

But it all began when Spade, an architectural grad student and mother pondering her own mortality, first thought seriously about a process she called “recomposition” in 2009.

“My kids were really fast growing up, and I had this moment of, ‘I’m mortal,’” said Spade. “I began to think, ‘What do I want for my own body when I die? How does design play a role, and why aren’t there eco-conscious alternatives?’”

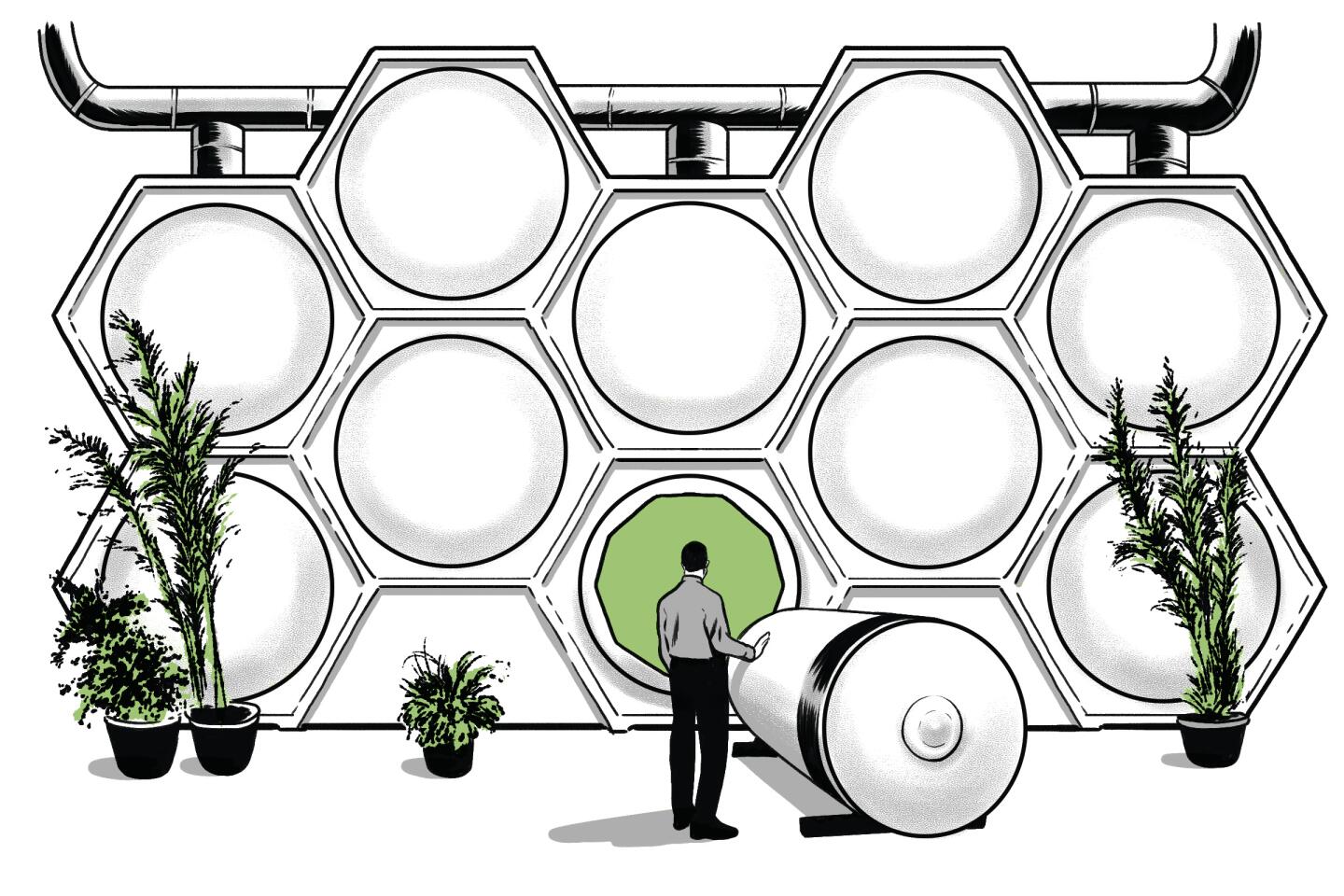

Thus began her Urban Death Project to look at eco-friendly and affordable ways to dispose of the deceased in urban areas. She initially designed a “Recomposition Center,” a tall structure with circular ramps, where people could carry their loved one’s body to the top, to be covered in wood chips, alfalfa and straw, and slowly decompose to the bottom, with their soil added to nourish a community garden. She spent nearly 10 years researching human composting techniques, including working with soil scientists at Washington State University perfecting techniques farmers had been using to compost dead livestock.

When it became clear that people didn’t like the idea of mingling remains, Spade changed her design to individual capsules containing the human remains and organic material, stacked in a honeycomb grid. In 2019 she successfully lobbied the Washington state Legislature to legalize natural organic reduction and, with the help of investors, opened her mortuary Recompose in 2020.

Another Washington facility, Earth, plans to open a second facility in Nevada this summer, making access easier and cheaper for Southern California residents. And in the first of what will probably be other such collaborations, the family-owned Clarity Funerals and Cremation in Anaheim has partnered with Return Home to offer a package deal for people in Southern California who want to compost their loved ones in Washington.

Former Assemblywoman Cristina Garcia said she wrote California’s law and spent three years lobbying her fellow legislators because she felt residents here needed more Earth-friendly choices for burials.

“I love the outdoors and I really want to be a tree in my afterlife,” she said. “My family has a crypt in Mexico, where there are no trees or shade around …. I want my soil to be used specifically for a plum tree, my favorite fruit, and my loved ones can visit me there.”

Garcia said she wanted a much quicker start time for California’s law but agreed to the 2027 date to satisfy concerns from the state Cemetery and Funeral Bureau, which wanted more time to set rules. “I didn’t want to risk it not getting passed,” she said.

A ‘death care’ revolution

The fact that California’s law won’t be in effect until 2027 has frustrated potential users, but it hasn’t stopped them. The three natural organic reduction mortuaries operating in Washington have reported steady business from out-of-state customers, especially Californians, who are either flying or driving their deceased loved ones north.

How human composting works

Depending on the mortuary, the cost of human composting can range from $4,950 at Earth and Return Home to $7,000 at Recompose. People from out of state must also cover costs like transportation and preparing an unembalmed body to be safely shipped. Return Home’s partner Clarity charges Southern Californians $6,950, plus the cost of air freight to ship the body to Seattle, about $410 on Alaska Airlines, plus taxes and security screening fees. Once Earth opens its facility in Nevada, it will only charge Southern Californians $4,950, without additional transportation charges, because it’s closer to the region, said communications director Haley Morris.

And each mortuary has its own patented processes and unique feel.

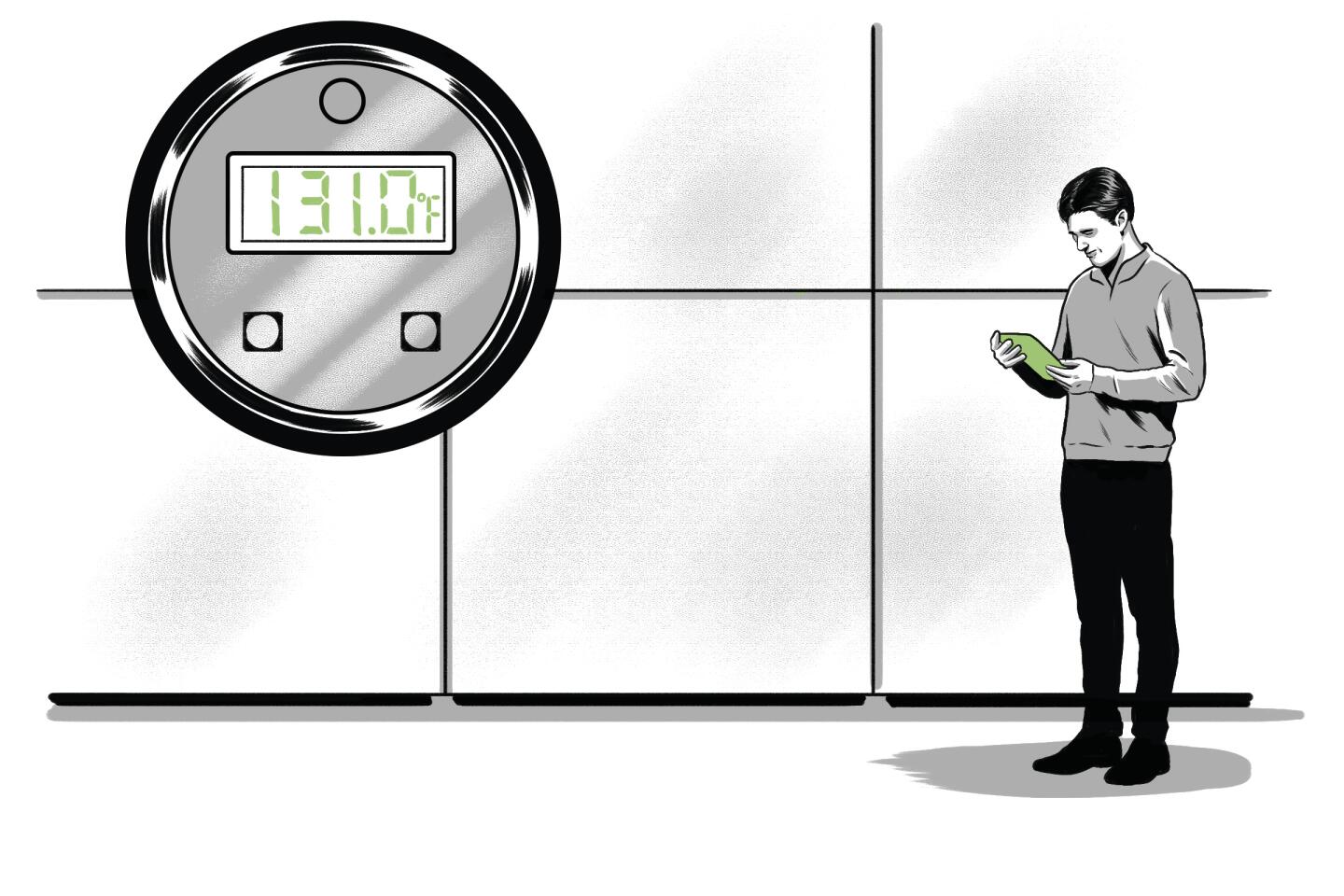

Earth, in Auburn, Wash., promises the quickest composting — 30 to 45 days in a facility where spaces for 78 vessels are stacked three-high in the so-called laying-in area. The spotless room with pale green walls is deliberately huge to accommodate for growth, said facility manager John Lawrence. In its first year, Earth cared for 200 bodies. “Our goal,” he said, “is to make this available to as many people as possible.”

Not many relatives request an in-house service, Lawrence said, but for those who do, there are white folding chairs set up in a corner of the cavernous room.

Recompose in south Seattle has a more artistic vibe. There’s a quiet room where families can wash and anoint their loved one’s body before it enters the vessel. Services are held in a high-ceilinged room with a chapel-like feel, with tall, narrow inserts of green glass in one wall that provide murky glimpses of the hexagonal array in the next room where the bodies are composted.

Connecting the two rooms is a short tunnel — inscribed with the words: “May we not live in fear of decomposing, but in awe and gratitude of our future Re-composing” — through which the vessels pass on their way to composting.

Return Home, also in Auburn, is the most touchy-feely of the three. At Earth and Recompose, once a body goes into the vessel, family and friends aren’t expected back until the soil is ready for delivery.

Return Home started that way too, until it discovered something “totally unexpected,” said CEO Micah Truman — people wanted to personalize the vessels of their loved ones with photos and drawings, or just drop in to sit near them. So Return Home installed sliding forest-themed panels in front of each vessel to keep them private. It laid rugs on the concrete floors, put out comfy chairs, pillows and blankets and welcomed family to visit whenever they were open.

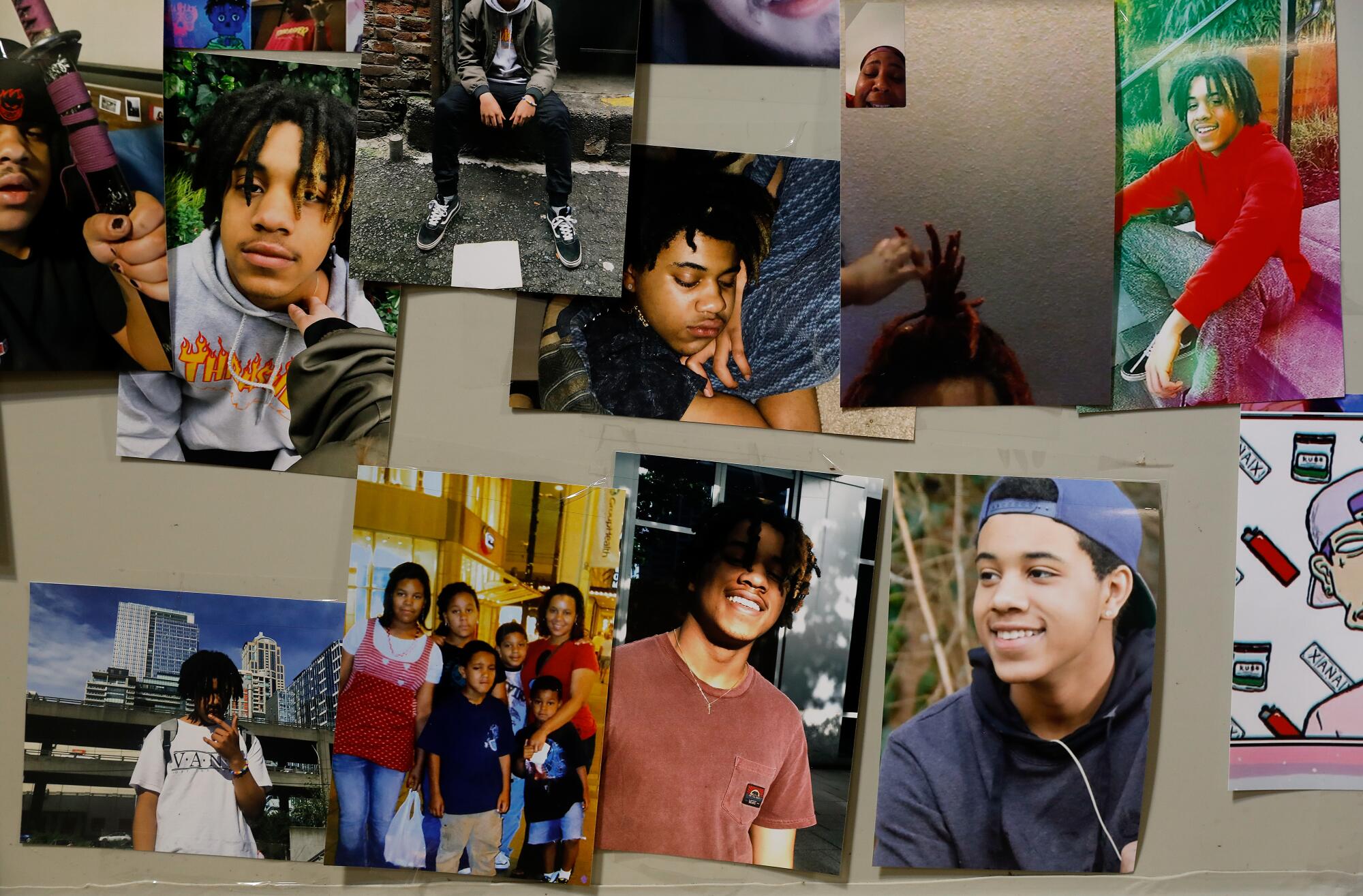

Those amenities made all the difference to McKelle Hilber, a teacher in Seattle who couldn’t imagine burying or cremating her 23-year-old son after his death in early 2023. “As soon as I read about terramation, I instantly knew this was exactly what Samah would’ve wanted,” she said.

Terramation is a trademarked term invented by Truman. “You don’t say, ‘I’m going to incinerate Mom.’ You call it ‘cremation,’ and it sounds like a milkshake,” he said. “We came up with terramation — ‘terra’ for earth and ‘mation,’ as in transform — because if we have a better lexicon, it will help people have less fear.” Relieving the fear that surrounds death is one of Truman’s big missions — the mortuary even sells merchandise with messages such as “Soil yourself” and “I’d rather be compost.”

Samah’s laying-in service with close friends and family was “cathartic and comforting,” Hilber said. “He was such a beautiful creative person who loved life, it just seemed like the perfect way to honor him,” she added. “We were able to see him in his vessel, write him letters and even include his favorite candies, Nerds.”

After a visit to Return Home’s facility, the owners of Clarity Funerals decided to change their personal burial wishes.

“With cremations, you’re basically getting a box of carbon. With terramation, you get a box of soil, to literally give your body back to the earth,” said Lauren Williams, Clarity’s director of operations. “I don’t usually talk about my job because, cremation and the funeral industry … people think it’s kind of sad. But when I talk about terramation, it’s actually beautiful and people are really interested.”

But the process can still feel scary, as Heidi Heffington of Anaheim learned when she chose terramation for her 83-year-old mother, Wilma, who died on July 6, 2023. (Heffington asked to not use Wilma’s last name for privacy in death.) Just three weeks earlier, Wilma had been dancing with her son-in-law, Joe, at the memory care facility where she lived, but then she got pneumonia that irreparably damaged her lungs.

Wilma was a vegetarian who loved animals and nature and resisted medications whenever possible, so the idea of embalming her mother was out of the question, Heffington said, and cremation felt too violent. So she and her husband flew to Return Home to lay her mother to rest. Since it was the first composting funeral organized by Clarity, Williams and some of her staff flew up for the service too.

When they arrived at the mortuary, however, Heffington panicked. She remembered as a child seeing a relative who was unrecognizable in his open casket, and she was filled with fear — how would her beloved mother look a week after her death?

Return Home dresses bodies in short cotton-bunting gowns and slippers made specially for its services. Wilma wore a gown accented with pink buttons to match the rosy nail polish on her fingers. The staff used a hydraulic sling to gently lift her inside a vessel half filled with a mixture of alfalfa, sawdust and straw. Then they moved the vessel out to the service area, next to panels of tall trees.

The Heffingtons approached the vessel slowly, carrying two dozen long-stemmed red roses. Using a small platform, they could easily reach inside, and upon seeing her mother, Heffington gasped. Wilma looked serene and a little ruddy cheeked — a natural reaction to refrigeration, services manager Katey Houston said.

“She looks like a little angel,” Heffington murmured, clutching her husband’s hand as they began speaking to Wilma gently, dropping the roses around her small, still form. And then Heffington was crying, along with everyone else. Even Williams, the seasoned funeral director, was wiping her eyes.

When they finished their goodbyes, however, Heffington was smiling. Part of her relief was the aroma, like fresh bedding in a stall. “She would love that natural smell,” she said. “It feels peaceful. I’m so glad she’s here.”

That day Heffington was uncertain about what she would do with her mother’s soil, but three months later, she and her husband took it all. “I didn’t feel it was right to leave some of her soil in another state,” she said. They got 10 bags worth, much more than they expected for her petite mother, Heffington said, and spread it under some trees in Los Angeles, in a spot she had loved.

“Make sure you tell people, you have to come up with a plan for what you’ll do with the soil, because it’s a lot,” Heffington said. But she has no regrets about choosing terramation.

“I wish I could have talked to her about it ahead of time, but I feel I made the right decision. It seemed more gentle to me … and I was so relieved to see her look so peaceful. That’s what I was hoping for her … and I hope she sees it that way too.”

Making a plan

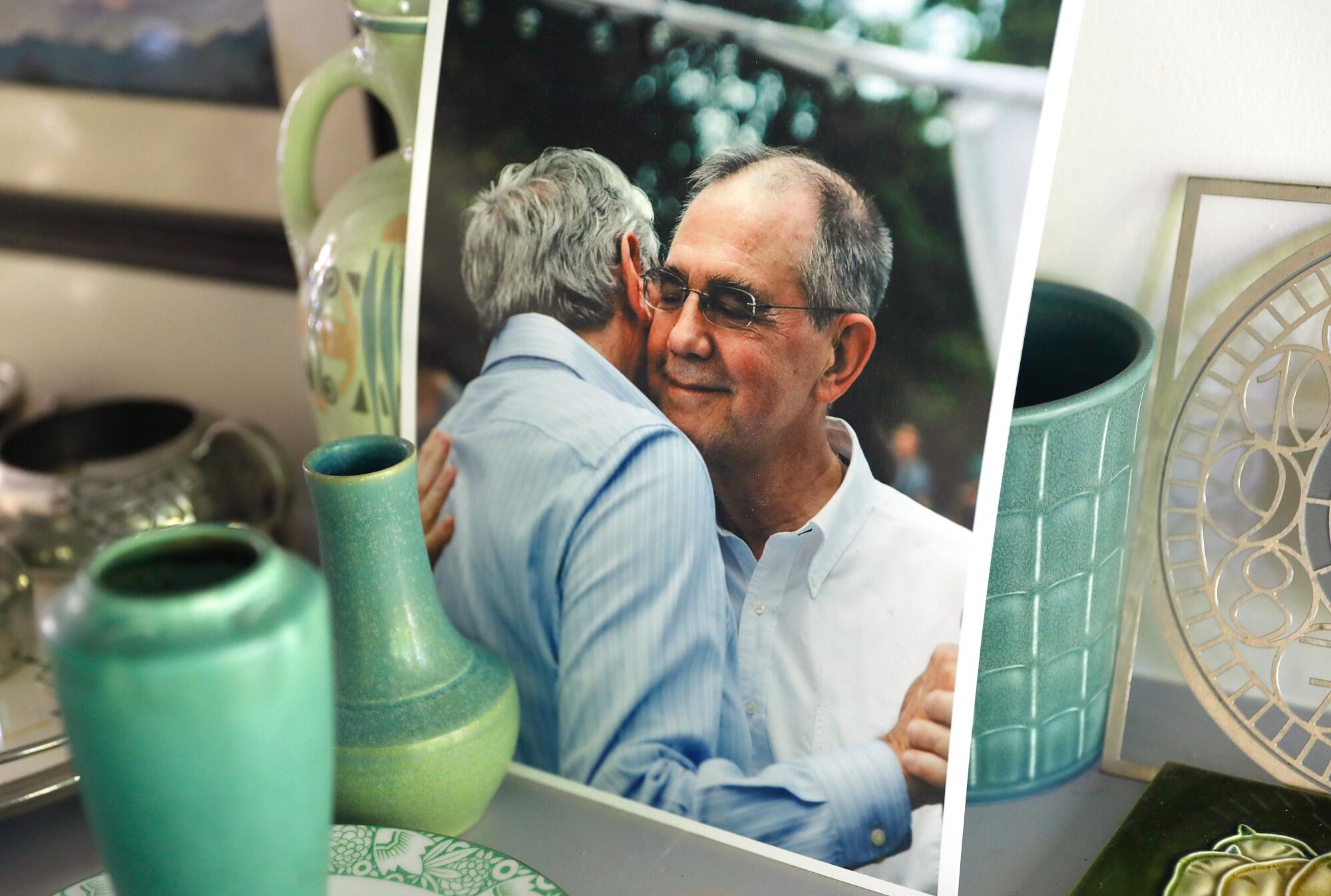

Wayne Thomas Dodge was a semiretired physician and avid gardener when he died on Sept. 5, 2021, at the age of 71. And it was his passion for Japanese maples that guided his family’s plan for his soil.

Dodge was carrying a box of books down some stairs in the Seattle home he and his husband, architectural historian Lawrence “Larry” Kreisman had shared for nearly 40 years when he slipped and fell backward. “In an instant,” Kreisman said, his active husband became a quadriplegic in constant pain, needing constant care. After several months, Wayne developed pneumonia and refused further treatment.

“He had been living for me, because I wasn’t ready,” Kreisman said. “But his life was not a joy. He was done.”

Before the fall, Dodge had changed his burial wishes from cremation to human composting, so Kreisman and his sister-in-law, Marie Eaton, called Recompose. The service was done via Zoom during the pandemic and when it came time to fill the vessel, Recompose included a staghorn fern Dodge had been nurturing for 50 years. “When he died, it died,” Eaton said, and became part of his soil.

Dodge had more than 45 varieties of Japanese maples, some planted in the ground but most in pots. Kreisman’s domain had always been indoors, so before he died, Dodge suggested that his husband give his potted trees away.

Thus, a few months later, Kreisman and Eaton lined the bed of a pickup with a tarp and filled it with Dodge’s soil. They parked it outside the couple’s home and invited friends, family and neighbors to take a tree and some soil. “So my brother is planted all over Seattle,” Eaton said.

Kreisman filled a beautiful copper bowl with the soil that remained. He keeps it in the kitchen now, near the stained glass windows that overlook a backyard dappled with maples of every color and size.

“It’s like having him around in some fashion that is not him, but still nurturing,” Kreisman said.

The soil felt warm in the sun and Kreisman held it tenderly. Nearby was a photo of the couple dancing, Dodge’s chin nestled on his husband’s shoulder, his eyes closed in apparent bliss, and suddenly Truman’s words at Return Home made sense: “The first thing someone does when they receive soil? They put their arms around it.”