When I was about 10 years old, I blurted out a sentence that would reshape my life.

“Marky Mark,” I said, “is sexy.”

I had only a partial understanding at the time of what that word meant, but I knew it applied to Mark Wahlberg, who in 1995 was a young rapper and muscled Calvin Klein model. I also knew, suddenly and irrevocably from that moment forward, that boys like me were not expected to have thoughts like that.

With queer lives and culture under threat, Our Queerest Century highlights the contributions of LGBTQ+ people since the 1924 founding of the nation’s first gay rights organization.

Pre-order a copy of the series in print.

My oldest brother, then about 14, immediately started teasing me as I clumsily tried to walk back the comment. I can still remember the pang of embarrassment. It was the epiphany so many LGBTQ+ people have in childhood, when we first realize that others see something different in us.

If no one has prepared us for that moment, if no one reassures us that being queer is perfectly normal, then the experience of being ridiculed or simply categorized apart from our peers can lead us to the opposite conclusion: that it is not normal. That it is bad.

It is in these moments that many of us promise ourselves that we will smother this difference. And by the time we realize, often years later, that doing so was a mistake, we have to dig and dig to uncover ourselves. We have to peel off masks, undo affectations and rediscover interests we had long denied as tells.

It takes even longer to truly love the difference, which is to say, ourselves.

I consider myself extremely lucky. I am a 38-year-old white cisgender millennial who was raised with tremendous privilege in a liberal Catholic family that has been nothing but supportive of me as a gay man. My parents are the best people I know. My oldest brother, the one who teased me, is gay. He and his friends, less than a decade after my Marky Mark comment, helped usher me out of the closet with tremendous care and encouragement.

For all those reasons, coming out was easier for me than it was for generations of older LGBTQ+ people who faced greater societal discrimination. It was easier for me than for many of my LGBTQ+ peers and those younger than me who lack my privileges — particularly those of color and who are transgender, and especially those who are both.

Still, there were years in which I was distracted from being happy by all the hiding and digging out I was doing. And it was because queer kids like me who grew up in the 1990s were rarely told that we were normal and deserving of happiness, and even less that we were full of potential.

That is what comes to mind today when I see conservative leaders, right-wing provocateurs and even some well-meaning parents fighting vigorously against the idea that their kids — that any kids — might benefit from hearing something positive about LGBTQ+ people.

Across the country and, indeed, across California, there is a growing war over what kids can be taught about queer issues. Conservatives want to ban the mere mention of queer people in schools and forbid LGBTQ+-inclusive school curricula. They want to ban drag queens from reading to kids, ban pride flags in classrooms and ban pride merchandise in stores. They want to ban young adult books with queer characters, ban gender-affirming medical care for transgender kids and try again to ban same-sex marriage, which provides many queer kids with hope for a fulfilled future.

With the protection of children as their stated rationale, today’s most ardent conservatives have taken up as a cornerstone of their political platform the idea that our nation and its children would be a lot better off if everyone under the LGBTQ+ umbrella were shoved collectively back into the closet, so that the rest of the country might move forward pretending we don’t exist.

But we do exist. And thank goodness.

LGBTQ+ people have helped define this country. Our contributions to the nation’s cultural identity are indelible.

Throughout history — but especially in the last 100 years since the 1924 founding of the nation’s first gay rights organization — LGBTQ+ people in California and beyond have defined art, fashion, music, film, literature and theater for the modern audience.

They have reshaped American cities, modern science, our sense of religion and virtue and our understanding of love, sex and family. They have honed and improved American democracy and the rule of law, for us all.

It is LGBTQ+ people, and particularly the most marginalized among us, who have made us all blessedly, brilliantly aware, in a quintessentially American way, that we are more than the boxes we are born into.

This essay serves as an introduction to Our Queerest Century, a project that includes six essays from queer writers, a four-piece news analysis of a groundbreaking national poll and other contributions from queer and allied artists and journalists both in and outside The Times’ newsroom.

In all, it articulates something I wish I had been told when I was 10 — that queer people should not just be accepted but celebrated.

When Beyoncé became the most-awarded artist in Grammy history in 2023 with “Renaissance” winning for best dance/electronic music album, she thanked the normal lineup: God, her parents, her husband, Jay-Z, and her kids watching from home.

But she also thanked her gay Uncle Johnny, who introduced her to dance music, and the queer community at large, for their “love and for inventing this genre.”

It was an acknowledgment of the tremendous influence queer people have had on dance music, from one of the industry’s reigning queens — who drew from queer artistssuch as Big Freedia for her album. It was also an important example of LGBTQ+ people getting their proper due as cultural creators, which hasn’t always happened.

For too long, LGBTQ+ history has been cast as a niche subject, conflated with the fight for queer rights. If Americans are taught about LGBTQ+ people at all, it is often through a condensed, half-century storyline that starts with the Stonewall uprising in 1969, notes the horrors of AIDS in the 1980s, and ends with marriage equality in 2015.

But queer influence is so much grander than that.

It is found in the work of queer artists and tastemakers, but also of so many of their straight, cisgender counterparts who — like Beyoncé — drew on their creativity and willingness to break boundaries. The queer aesthetic was the secret of late queer performers such as Freddie Mercury and Juan Gabriel, but also gets tapped in healthy doses today by performers such as Harry Styles and Bad Bunny.

Starting in the 1950s, gay poet Allen Ginsberg and his fellow queer Beat writers drew inspiration from queer writers of the past, such as French poet Arthur Rimbaud, to produce now seminal works of American literature, including Ginsberg’s “Howl” and Jack Kerouac’s “On the Road.” Their work changed how a generation of young Americans viewed the world, helped launch the counterculture movement of the 1960s and deeply influenced a slate of other prominent artists, such as Bob Dylan and the Beatles, who went on to change the cultural fabric themselves.

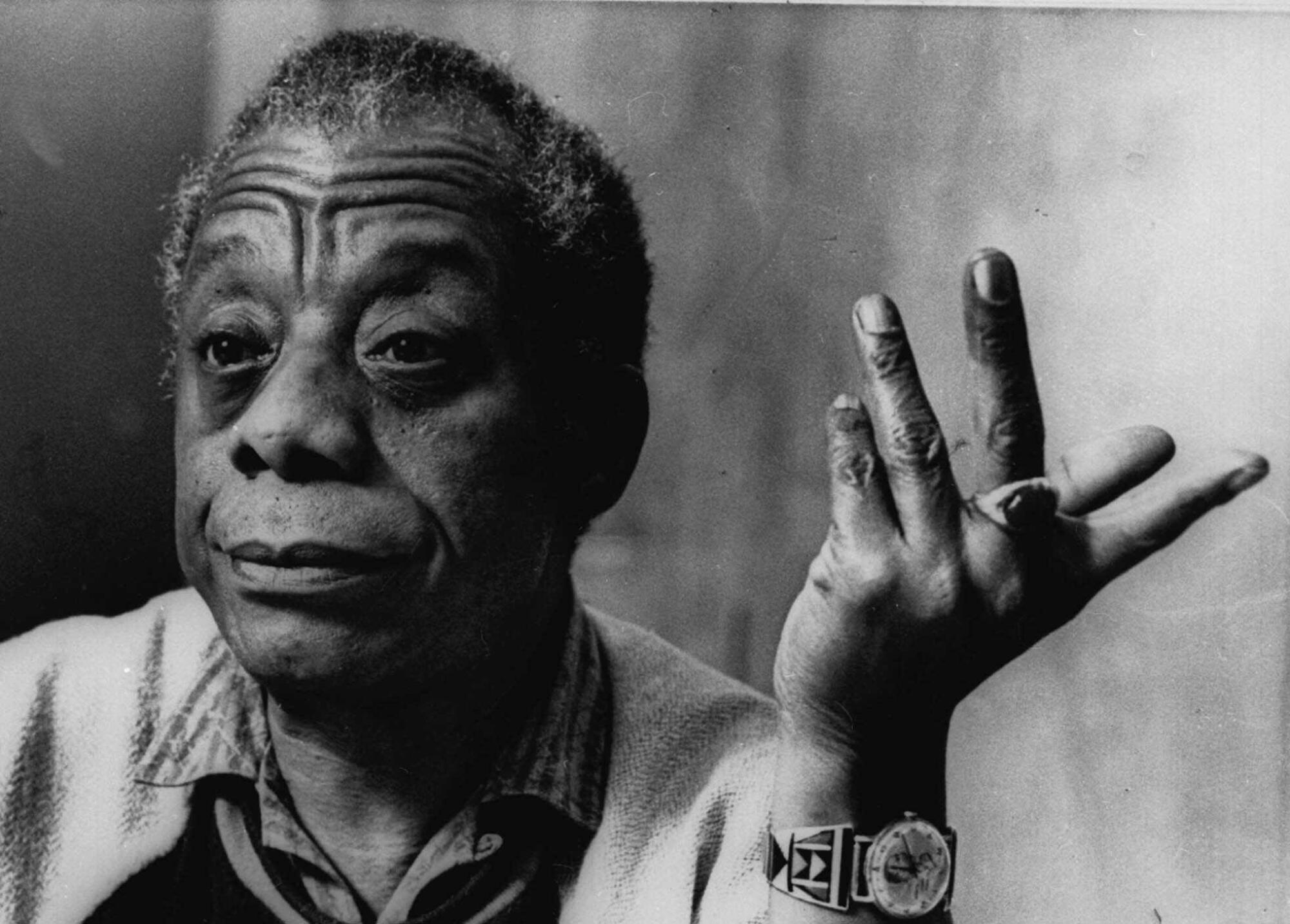

Gertrude Stein and Alice B. Toklas convened and inspired an entire network of “lost generation” artists and writers in their Paris salon. James Baldwin wrote thunderbolts of truth about American racism that changed the way people have understood and debated the issue since. Tennessee Williams wrote raw, lyrical plays that infused American theater with a new emotional dialect. Little Richard laid the foundation for rock ‘n’ roll.

American painting was never the same after Andy Warhol. American nightlife was never the same after Studio 54. American sports would not be nearly as vibrant without the long line of queer women, from Billie Jean King to Megan Rapinoe and Brittney Griner, who have inspired generations of young girls to compete. There would be no “high five,” in sports or elsewhere, without gay Dodgers player Glenn Burke helping invent it.

Queer people have shaped the fashion industry for so long it seems trite to try to articulate the vastness of their influence. Queer fashion designers, stylists and makeup artists — including contouring drag queens — are responsible for much of what Americans see in movies, magazines and the mirror. Young queer Latinx people, including dancers and club kids, have been shaping American language and culture for decades, from the House of Xtravaganza choreographing the video for Madonna’s “Vogue” in 1990 to Michaela Jaé Rodriguez becoming the first transgender woman to win a Golden Globe for her poignant portrayal of ballroom mother Blanca on the FX series “Pose” in 2022.

With their uniquely intersectional identities and deep understanding of inequality, queer people also have for generations been at the forefront of American social justice movements. Queer people such as Bayard Rustin, Pauli Murray and Kiyoshi Kuromiya played important roles in the civil rights movement. A long line of queer women — from Susan B. Anthony to Jeanne Córdova to Kitty Cone — have played pivotal roles in the suffragist, feminist, women’s rights, disability rights and reproductive rights movements.

I wish someone had taught me this as a kid.

One month after I was born, in December 1985, this newspaper conducted a groundbreaking national poll on attitudes toward gay and lesbian people and AIDS, which was killing gay men at a terrifying rate.

Nearly three-quarters of 2,300-plus respondents, or 72%, said same-sex relationships were always or almost always wrong. More than 6 in 10, or 64%, said they would be very upset if their child was gay. Despite it being clear that AIDS was not confined to gay people, 28% said they somewhat or strongly agreed that AIDS was God’s punishment for gay people and 23% said people with AIDS were “getting what they deserve.”

Such beliefs were rooted in an abiding ignorance of gay people at the time.

Less than a quarter of the poll’s respondents said they’d had a relative, friend or co-worker tell them they were gay or lesbian. In addition, 21% said they suspected people around them might be gay but weren’t sure. A majority, 54%, said they did not know or believe any of their family members or associates were gay.

Much has changed over the course of my lifetime.

As part of this project and in partnership with the California Endowment and NORC at the University of Chicago, The Times this year launched a new national poll on LGBTQ+ issues, asking some of the same questions from 1985 but also a host of new ones.

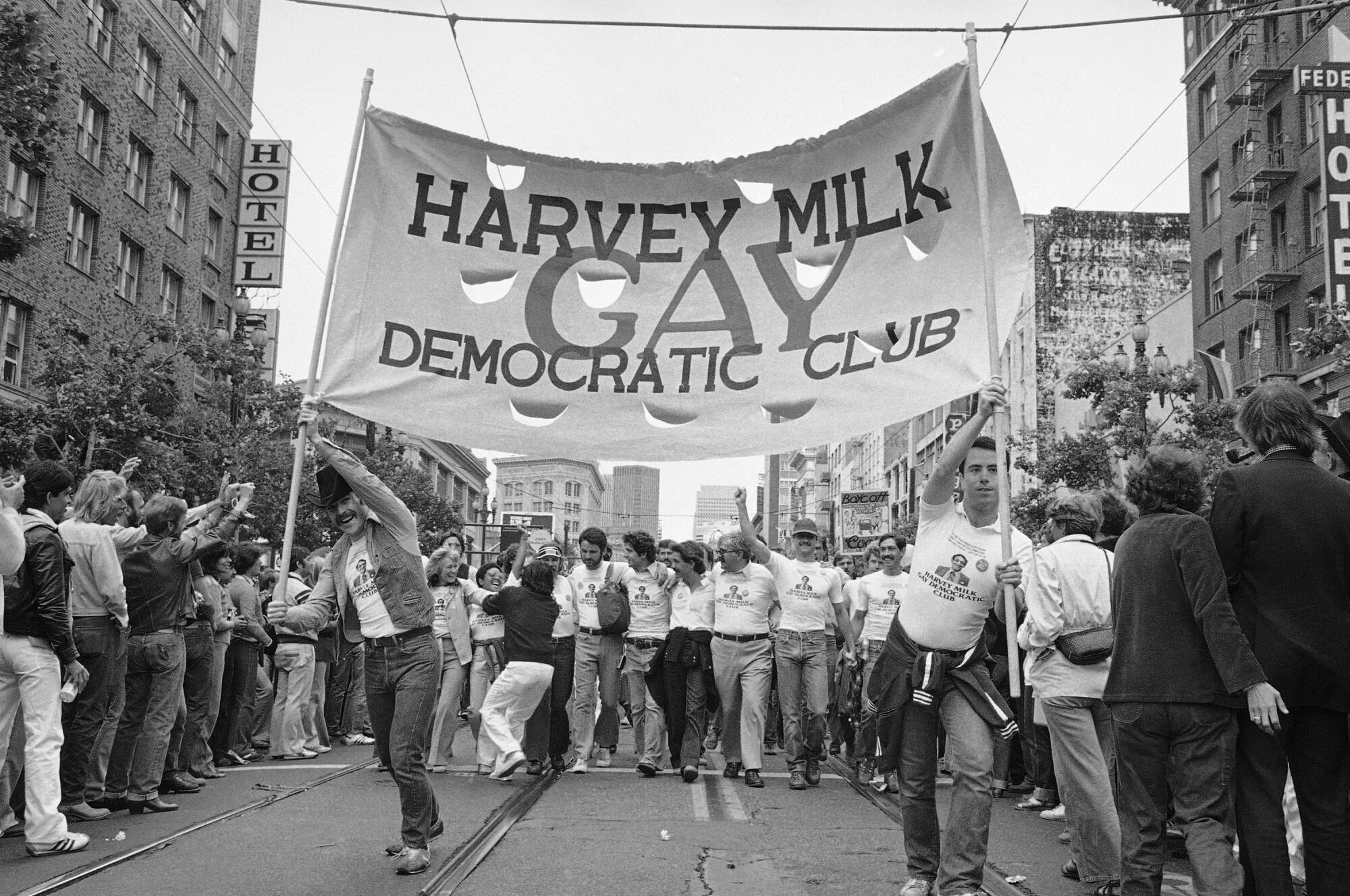

The poll showed the percentage of people who have had a relative, friend or co-worker come out to them as gay or lesbian has shot up to 72%, while the percentage of people who consider same-sex relationships always or almost always wrong has plummeted to 28%. Only 14% of respondents today said they would be very upset if their child was gay.

The findings are consistent with other research showing that anti-queer discrimination eases with awareness and familiarity with gay people. The findings reflect decades of progress won by gay and lesbian activists who have unapologetically claimed their identities and accomplishments in the public sphere.

And yet, discrimination persists, particularly for LGBTQ+ people who remain less understood than gays and lesbians.

While 80% of respondents said they somewhat or strongly approve of gay and lesbian people living their lives as they wish, that number dropped to 67% approval for transgender and nonbinary people. More than a quarter of respondents — 26% — said they would be very upset if their child was transgender or nonbinary.

At the same time, only 27% of respondents said they’ve had a relative, friend or co-worker come out to them as transgender or nonbinary.

Ignorance of LGBTQ+ people remains a major threat, informing the conservative crusade against us. Today’s anti-queer forces cast all LGBTQ+ people as “groomers” to make the very act of coming out — our superpower in the fight for acceptance — seem like a danger to children.

They target gender nonconforming people with particular vitriol, casting their very existence as a threat, because they know ignorance begets fear, and fear is a strong baseline for the discrimination they seek.

The reality, however, is that knowing, and appreciating, queer people does not threaten children. It protects them.

Most queer youth in this country have been victimized because of their sexual identity, gender identity or gender expression, but surveys of LGBTQ+ kids by queer rights groups have shown that such abuse is diminished in schools where queer people’s contributions are celebrated.

The contributions we ascribe to queer people are undoubtedly an undercount, given how many — past and present — have been forced to hide.

Still, we know the queer community’s influence has been huge thanks to the bravery, and in some cases privilege, of queer people who did come out, particularly in the last 100 years.

Before founding the Society for Human Rights in 1924, Henry Gerber served in the U.S. Army in Germany, living along the Rhine from 1921 to 1923, during the Weimar Republic between the two World Wars.

Gerber traveled often to Berlin, which at the time was a vibrant hub of queer expression and home to queer bars and publications advocating for queer rights, to which Gerber subscribed. It was also home to the Institute for Sexual Research, which conducted LGBTQ+ research and provided some of the world’s earliest gender-affirming care before the Nazis ransacked it.

Upon his return to Chicago, Gerber resented the relatively unchallenged persecution of queer people in the U.S. and decided to launch his own gay rights organization here.

According to an article he wrote decades later in One, an important gay rights magazine founded in Los Angeles in 1952, Gerber and a few associates drew up paperwork, obtained a state charter and set out to gain as many members as possible, in part by launching their own publication called Friendship and Freedom.

Instead, they were arrested on trumped-up obscenity charges and subjected to expensive litigation before the case against them was thrown out for lack of evidence. Gerber escaped a prison sentence but lost his post office job and life savings and ultimately reenlisted.

Gerber later recalled being shamed into silence by the same baseless allegations of predation lobbed at LGBTQ+ people today. The “parting jibe” of the detective who worked the case, he noted, was to ask whether the society’s goal had been to “rape every boy on the street.”

Gerber’s experience, deeply sad, also signaled a monumental shift in the right direction.

In big cities across the country, queer people were beginning to carve out spaces — and influence — for themselves. In New York, queer artists and intellectuals were leading figures in the Harlem Renaissance. In Los Angeles, a thriving queer community blossomed alongside the early film industry. In San Francisco, long-existing queer enclaves dug ever-deeper roots and grew larger, particularly with the influx of young queer service members during and after World War II.

The popularized notion that the gay rights movement began with Stonewall in 1969 belies the efforts of these communities to build the foundation of that movement in the decades prior — especially in California.

The Mattachine Society, an early gay rights group, was founded in L.A. in 1950, while the Daughters of Bilitis, an early lesbian rights group, was founded in San Francisco in 1955. Throughout that decade, drag queen José Sarria infused his performances at the Black Cat in San Francisco’s North Beach neighborhood — where Ginsberg and other queer Beat writers gathered — with political calls for queer acceptance.

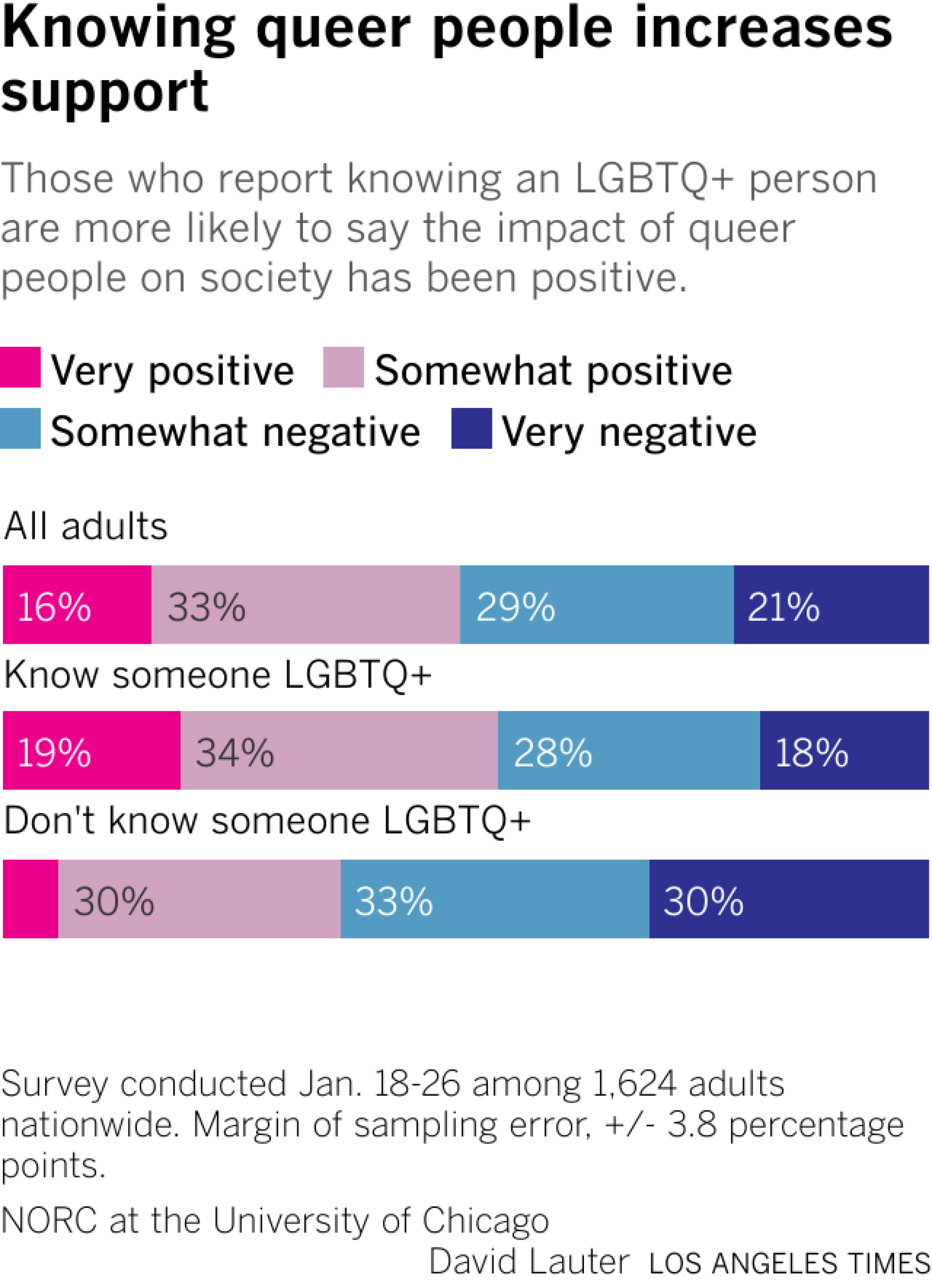

By 1959, gay people had such a strong foothold in San Francisco that it became a major point of contention in that year’s mayoral race. Two years later, Sarria would run for a seat on the San Francisco Board of Supervisors — preceding Harvey Milk’s successful 1977 run for such a seat by more than 15 years.

Milk’s win and the rejection by voters in 1978 of a statewide ballot measure that would have barred gay and lesbian people and their allies from serving as public school teachers in the state helped solidify California’s reputation as a safe haven for queer people — drawing more in. Today, California has the largest LGBTQ+ population in the nation and touts its role as a progressive leader on LGBTQ+ issues and a staunch defender of queer rights.

Of course, there was always pushback. Conservative leaders raised hell about queer people having the audacity to organize in the 1950s, and police regularly cracked down on gay bars and other queer gathering places for most of the last century. Many in the media, including at The Times, cast queer people as threats to the nation’s children and sought to expose them. Authorities banned queer material, including movies with queer references and books such as 1928’s “The Well of Loneliness” by Radclyffe Hall, and warned up-and-coming artists against producing more.

But an increasing number were no longer listening.

In 1948, Gore Vidal published “The City and the Pillar,” about a gay man’s struggle to find companionship before and after World War II. In 1956, Baldwin published “Giovanni’s Room,” a trenchant tale of social pressures destroying a gay couple in postwar Paris. The same year, Ginsberg candidly took on queer ideas with “Howl.” Two years later, the magazine One secured a landmark Supreme Court victory against queer censorship that emboldened LGBTQ+ artists and activists even more.

Queer members of the New Left made coming out into a clarion call as they demanded gay power and liberation in the late 1960s, and it has remained a key strategy of queer activists ever since — a declaration not just of pride, but of purpose and personhood.

In a 1984 interview in the Village Voice, Baldwin said he knew writing “Giovanni’s Room” nearly 30 years prior was risky, but the only alternative had been worse: to “stop writing altogether.”

“The question of human affection, of integrity, in my case, the question of trying to become a writer,” he said, “are all linked with the question of sexuality.”

I grew up with the never-in-doubt love of a big family, a truly golden-hearted mother and two clear reassurances in middle school — from my loving father and a beloved seventh grade teacher — that there is nothing wrong with being gay. Those things gave me the courage to admit who I was to myself early on and to come out at 15 to two of my closest friends.

But I had also attended Catholic schools and remember wrestling from a very young age with the idea that being gay is a sin. I can still feel the sting of being called “gay” on the school playground, and the crippling social stigma that came with being queer back then. Even as I was coming out, I was still internalizing shame. It would stick with me for years.

Discovering you love yourself, though, is a powerful thing. It can change your life.

For me the process began when I walked at age 20 into a small, second-hand bookstore in Barcelona, where I was studying abroad.

Almost immediately, I noticed a book set atop others, with a tan young man in a small white bathing suit on its cover. It was “The Temple” by Stephen Spender, published in 1988 but conceived and partially written long before, about an Oxford poet who was also 20 and traveling abroad in the summer of 1929 — during the same sexually liberated Weimar era that had inspired Gerber.

I shelled out the euros, took the book home and devoured it. I then set out to read everything else I could find by Spender and his queer cohort, including novelist Christopher Isherwood and poet W.H. Auden. The more I read these and other queer writers, the more I understood the queer struggle as a defiant show of strength, queer people as the protagonists of the story, and their fight as my own.

I took up LGBT Studies as a second concentration when I returned to the U.S. for my senior year of college, and slowly made progress. I started seeing all the ways in which the anti-LGBTQ+ vitriol I’d heard as a kid had burrowed into my brain, eroding my sense of self-worth and my belief that love could possibly be in the cards for me.

I’d buried myself for 10 years, from Marky Mark to the Barcelona bookstore, and it took another 10 — all of my 20s — to get out. Then, suddenly, there I was.

In 2016, when I was 30, I splurged to buy a cheap round-trip ticket to Sydney on a whim. When I met an Australian guy named Aaron out at a gay bar one night, it felt easy and light; we bantered well, and he had big dimples, and I was myself. I was there.

Aaron and I have now been married for six years. We are close with our wonderful families on both continents. In November, I officiated the wedding of my brother Conor and his husband, Paul.

Aaron and I live in San Francisco, walking distance from the brilliantly queer Castro neighborhood. We have gay coffee table books and our shelves are full of queer literature, including my old copies of Baldwin and Spender. There are also newer queer titles that have been subject to bans, such as Maia Kobabe’s “Genderqueer,” and sweet books for queer kids that I wish had been available to me in middle school, such as Alice Oseman’s “Heartstopper” series and Becky Albertalli’s “Simon vs. the Homo Sapiens Agenda.”

Living in San Francisco is like living in my teenage dreams. I can spend hours perusing local, queer-friendly bookstores (Community Thrift, Dog Eared and Fabulosa), and I see queer literature, art and history everywhere I turn. San Francisco today may be the best place for queer people to live in all of American history, and it brings me great joy to see so many of us — including queer kids — living open, happy lives here.

The problem is that too many others are still growing up and living in the opposite sort of environment, in deserts of queer understanding where they constantly hear negative things about being LGBTQ+ and have no access to the queer books and college courses and family guidance that were so crucial in my own digging out process. To make it worse, anti-LGBTQ+ conservatives are actively working to snuff out the rare glimpses of queer culture and joy that do exist in such places.

That is the real threat to children today.