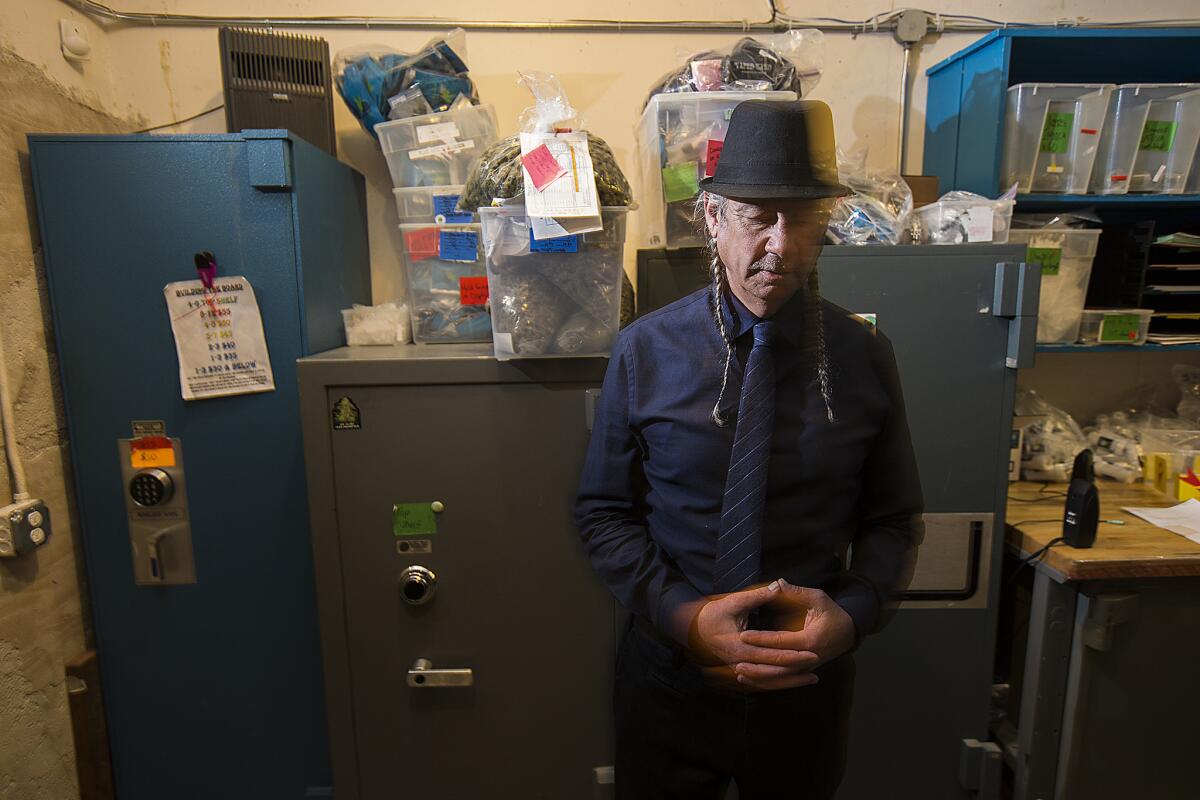

Steve DeAngelo, the co-founder and executive director of Harborside Health Center in Oakland, stands in the room where the medical marijuana dispensary’s cash reserves are kept. He does not believe he will have a problem getting a state license despite a felony in his background.

In 2001, Steve DeAngelo agreed to help a friend by attending the delivery of nearly 200 pounds of marijuana in a Maryland trailer park and verifying the quality of the product. In exchange, DeAngelo said he would get 10 pounds of the cannabis that he planned to distribute to medical marijuana patients in that state, where he lived at the time.

Instead, the police swooped in, and DeAngelo ended up convicted of felony possession of marijuana with intent to sell.

Fifteen years later, DeAngelo runs what may be the largest medical marijuana dispensary in the U.S., but a new law says he will have to get a state license by 2018 — and the state can reject applications from those with drug felonies on their records.

DeAngelo, whose Harborside Health Center in Oakland has annual sales of $30 million, plans to go through the appeal process.

See the most-read stories this hour >>

“My argument is simple: Cannabis should never have been made illegal in the first place,” he said.

Still, industry leaders say the new law could hurt hundreds of growers and sellers who planned to apply for state licenses but who have felony drug convictions on their records.

“It’s a huge issue,” said Casey O’Neill, board chairman of the California Growers Assn., a 500-member group representing cannabis cultivators in the state. “Twenty-five to 30% of our members are in this boat” with felony drug convictions, he said.

O’Neill, who grows cannabis and flowers at HappyDay Farms in Mendocino, was convicted of a felony marijuana cultivation charge in 2009. But he believes he will not have trouble getting a license because his conviction was expunged when he successfully completed probation without another offense.

He worries the new law will mostly hurt people of color, who he said bore the brunt of the war on drugs.

“You have populations that have been disproportionately prosecuted for cannabis cultivation, and to then not be allowed to participate in the regulated economy, it’s like a double whammy,” O’Neill said. “It’s totally unacceptable.”

The stakes are high. An estimated 1,250 medical marijuana dispensaries are operating in the state, with sales last year hitting $2.7 billion, according to industry groups.

The stakes are likely to get higher still in November, when voters are expected to be given the chance to vote on an initiative to legalize the recreational use of marijuana. If California voters approve recreational use, the total state market for cannabis could reach $6.6 billion in 2020, according to a recent report by New Frontier, an industry data collection firm, and ArcView Market Research.

Because of that, licenses to grow and sell marijuana will likely be very valuable.

FULL COVERAGE: Marijuana regulation in California

One sign of nervousness over the potential for disqualifications is a bill introduced by Assemblyman Rob Bonta (D-Oakland) that was written in a way to specifically exempt DeAngelo on grounds that he is a major economic driver in the state. But law enforcement officials have fought any effort to make it easier for felons to get licenses.

California voters legalized medical marijuana sales and use in 1996, but the Legislature only last year approved regulation of the growing, transport and sale of cannabis under the oversight of a new state Bureau of Medical Marijuana Regulation. Gov. Jerry Brown appointed Lori Ajax as head of the new bureau.

The law signed by Brown in October says the state “may” deny a license to an applicant who has been convicted of an offense that is “substantially related to the qualifications, functions or duties of the business” he or she wants to operate.

A substantially related offense includes “a felony conviction for the illegal possession for sale, manufacture, transportation or cultivation of a controlled substance,” which includes marijuana, the law says.

Violent felonies and those involving fraud, deceit or embezzlement also are grounds for refusal of a license.

However, the licensing agency also may determine that the applicant is “otherwise suitable” to receive a license if that person “would not compromise public safety,” the law says. At that point, the agency will conduct a review of the nature of the crime and “evidence of rehabilitation” of the applicant before deciding whether he or she is suitable for a license.

A certificate of rehabilitation issued by courts in California is one piece of evidence accepted.

Ajax will look at the criminal histories of prospective dispensary operators on a case-by-case basis and is still drafting guidelines to be used in the process, spokeswoman Veronica R. Harms said.

“The bureau will determine whether to issue a license based on the specific information contained in each application,” Harms said. “Many of the details about how to obtain a license will be determined during the regulations process.”

Growers will have to get licenses from the California Department of Food and Agriculture.

DeAngelo, who served three weeks behind bars, said his conviction was not expunged. Out-of-state convictions are not eligible for certificates of rehabilitation.

In response to DeAngelo’s situation, Bonta introduced a bill in February that would have exempted those with convictions outside the state as long as they are now authorized to operate in California.

“One of the things that came up as a policy discussion was the experience of one of those cannabis industry leaders in the state, who has helped innumerable patients and who has helped with the economy, and he’s from my own district,” Bonta said. “That’s Mr. DeAngelo. We wanted to make sure folks who have been good actors for a long time in California weren’t prevented from continuing to work in this industry.”

However, Bonta said he has decided not to pursue action on the bill after it was strenuously opposed by law enforcement, including the California Police Chiefs Assn.

The medical marijuana regulations were built “with strong protections against black market activity,” said Ventura Police Chief Ken Corney, president of the association. “A key component of these protections — and consistent with laws for other state licenses — is permitting the state to deny a business license to a person with a felony conviction if there is a public safety concern.”

Watering down the rules, the chiefs said in a letter to lawmakers, sets a negative precedent by “prohibiting the department from denying a license to a person with an out-of-state felony conviction. Such a rule has never applied to any other category of state licensing.”

Although DeAngelo was not named in Bonta’s bill, it was customized to include language that fit his situation. That raised eyebrows by others in the medical marijuana community.

“It’s an inappropriate use of the legislative process,” O’Neill said. “What we want to see is just a bill that says people who have a conviction for cannabis still get to play ball.”

New, broader legislation may be needed, said Nate Bradley, executive director of the California Cannabis Industry Assn.

“We want to open up the market as much as we can,” Bradley said. A lot of these felonies are for doing things that are now legal under this bill.”

DeAngelo said any legislation should be applied more broadly. He believes his clean record of running an Oakland dispensary that has served thousands of medical marijuana patients will help convince state officials that he deserves a state license.

See more of our top stories on Facebook >>

“I’m reasonably confident that I will be able to get a license, but I am still not satisfied with the treatment of prior felony convictions in the measure at all,” said the 57-year-old “ganjapreneur.” Like O’Neill, he worries about the impact on people of color, including those who may not have the means to hire a team of lawyers.

The law also troubles Alice Huffman, president of the California State Conference of the NAACP. She says she has a solution.

“They should take everybody for low-level drug crimes if they haven’t re-offended in the last 10 years and just wipe their record clean so they can participate legally,” Huffman said.

The clearing of records is justified, she said.

“The war on drugs has devastated our community. It was mostly black and brown people who were targeted. I think it’s unconscionable to let this industry come into being and not include people who were victims of this war.”

Bonta defended his attempt to help DeAngelo and other felons.

“I believe in second chances and I believe in new opportunities, and we have people who do have felony convictions because of the way cannabis has been treated,” Bonta said. “Not every state sees medical cannabis as the medication that it is. The war on drugs had all kinds of conservative policies with horrible outcomes for vulnerable communities.”

Follow @mcgreevy99 on Twitter

ALSO

A conversation with California’s first marijuana czar

California voters getting chance to fully legalize marijuana