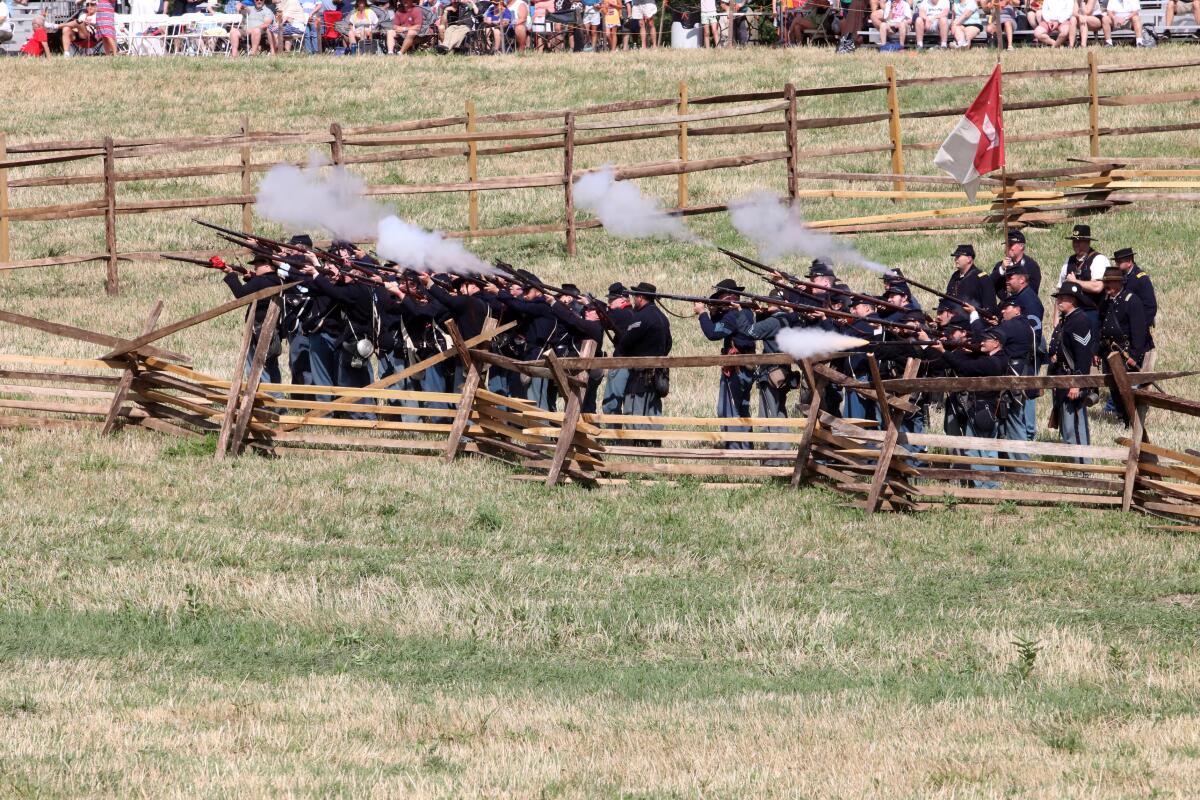

On a sweltering Saturday morning in early July, nearly 1,000 Civil War reenactors in full period regalia — along with cannons, muskets and bayonets — converged on the grounds of Daniel Lady Farm in Gettysburg, Pa., to commemorate the 161st anniversary of the Battle of Gettysburg.

Also there was a film crew and several actors who came to shoot scenes for Oscar winning director Kathryn Bigelow’s upcoming Netflix feature. The historic reenactment was to be used as a backdrop.

But Jean Marie Donnelly was troubled.

The studio teacher and designated child welfare worker was there to work with a 10-year-old actor. The production, she said, invited two young local boys dressed in Union costumes who were attending the reenactment with their grandparents to appear in a scene with her minor.

When Donnelly asked the production to see the boys’ child labor permits, she was told that there were none, in violation of Pennsylvania state labor laws. Nor did the production have legal parental permission to film them, she said.

Quickly, she surmised that the scope of their proposed activity went beyond passersby casually turning up during a film shoot. She also thought it was potentially dangerous.

The filmmakers wanted the pair, who carried what appeared to be muskets, to run around an area where there was a burning campfire, playing with the film’s young actor, she said. As the mercury edged toward 100 degrees that day, the children would be asked to do several takes. Donnelly noted there was no armorer present to inspect the gun props.

The veteran teacher refused to allow the producers to film the scene.

“If something happened with these muskets or they pushed my kid into the fire, that’s a health and safety issue,” said Donnelly, who documented the episode in a text message to a supervisor and in a complaint to SAG-AFTRA viewed by The Times.

Donnelly’s concerns echo the experiences of other teachers who say the system intended to protect the health and welfare of minor actors is subject to numerous conflicts and frequently falls short, according to a Times review.

Several people close to the Netflix production acknowledged they did not have work permits for the local children, but they and the boys’ grandparents disputed the teacher’s account. They said the boys carried cap guns that didn’t require an armorer’s inspection, there were no plans to film near a campfire and that they promptly complied with the decision to halt the scene.

“We take safety seriously on set. We would never put anyone in harm’s way,” said one of the individuals close to the production who was not authorized to speak publicly on the matter.

A Netflix spokesperson called the teacher’s account “inaccurate,” saying in a statement: “The minors in question brought their own toy wooden muskets to this location independent of our production. In an abundance of caution, once these items were brought to our attention, production safety personnel inspected to confirm they were wooden toys. No minors handled any weapons or were close to a fire.”

Donnelly is among 15 teachers, child labor coordinators and parents of child actors who described to The Times nearly two dozen incidents involving alleged violations around safety and education rules on film, TV and theater productions in California, Georgia, Florida, Illinois, New Mexico, North Carolina and elsewhere. These included incidents where teachers and parents say minors were not properly supervised or were exposed to unsafe working conditions.

“It’s a hugely flawed system that is really dangerous,” said Rachael Dimond, a studio teacher based in Georgia. “It’s just a matter of time before there’s another ‘Twilight Zone’ like situation,” she said, referring to the 1982 film set accident in which actor Vic Morrow and two children were killed.

The responsibility for the safety of children on set is shared by several adults. The director has ultimate authority, but the first assistant director, stunt coordinator and armorer also play key roles.

In March, the armorer on “Rust” was found guilty of involuntary manslaughter in the accidental shooting of the cinematographer on the troubled western. The tragedy mired the film in civil and criminal litigation and placed a renewed focus on the handling of firearms and safety protocols on sets.

Others have important safety duties as well, including set teachers, who have varying degrees of responsibility over their minor charges depending on the state involved and a host of factors.

However, many of the teachers told The Times that their ability to carry out these duties was thwarted by producers and parents, who aren’t always familiar with the rules, or the leading company that places them on film sets.

Donnelly says she was only able to push back because she is a California certified studio teacher who had the authority to do so. She and union representatives take the position that under California labor law, when a child actor resides in the state and both the company and the contractual arrangements for the film are also based here, then the state’s labor laws should apply. Designated as “studio teachers,” they accompany the young entertainers wherever they film and act as both educators and social workers with broad responsibilities, including the power to remove a minor from the set.

Under different circumstances, Donnelly said, “Those two boys would have gone right into the movie.”

“Was the entire cast and crew mad at me? Yes, but … I had to be vigilant.”

Neal W. Zoromski, a veteran prop master, said Donnelly acted appropriately.

“I understand the spontaneous nature of working with background people,” Zoromski said, but he noted that any item introduced on a film “needs to be vetted and cleared by the proper person,” including a toy gun. “This has a lot of warning buzzers.”

A patchwork of protections for minors

During the industry’s Golden Age in the 1930s and 1940s, few restrictions were placed on young entertainers. Infamously, one of the era’s most prominent, “The Wizard of Oz” star Judy Garland, was said to have worked 18-hour days, six days a week. To maintain this arduous workload, Garland was given amphetamines to prop her up and keep her alert and sleeping pills to calm her down.

Over time, various laws and union rules were enacted to protect children — often in response to revelations of abuse and exploitation.

The recognition that teachers could play a greater welfare role took on more urgency in 1982, when a helicopter crashed during the filming of “Twilight Zone: The Movie” in northern L.A. County. It was cited as an egregious example of what can happen when rules that are in place are flagrantly violated and when no one is looking out for the interests of minors on sets.

Even with mandates for background checks, education and a requirement that a parent or guardian must accompany minors on set, the rules and regulations can vary widely from state to state. A pastiche of labor laws are generally less stringent than those in California, which critics say can create gaps around minors’ welfare and safety.

Despite the patchwork of protections, set teachers play an important supervisory role and act as an advocate for the welfare of young entertainers. As teachers, they are legally obligated to report any abuse or harm to a child.

An important player in the industry is a company called On Location Education, the largest supplier of set teachers that has placed educators on thousands of productions such as “Black Adam,” “School of Rock” and “The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel,” according to its website.

‘A hugely flawed system’

On Location Education was founded in 1982 by Alan Simon, then a public school substitute teacher and aspiring actor.

Simon has said that after his acting gigs dried up, he returned to teaching full-time. A friend helped him land a job tutoring the children in a new Broadway musical, “Frankenstein.” While the play bombed, it sparked a career shift for Simon.

The Screen Actors Guild had recently established a set of national educational standards for minors working in entertainment. Teachers were now required to be present on sets, providing children with three hours of daily schooling when working three or more consecutive days.

The new rules created a business opportunity to provide a network of certified teachers to work on film, television and theatrical productions.

From the start, OLE had no shortage of clients.

Simon boasted that OLE teachers had tutored a then 17-year-old Claire Danes during the filming of “William Shakespeare’s Romeo + Juliet” and 16-year-old Natalie Portman while she appeared on Broadway playing Anne Frank.

In addition to providing teachers to film sets, OLE coordinates education compliance-related services, including work permits, welfare specialists, labor law expertise and chaperones.

The company, based in Westchester County, N.Y., is now incorporated in nine states as well as in Canada and the UK, according to its website.

In 2015, OLE suffered what appeared to be a major setback when Rocart Inc., a producer of many Nickelodeon kid’s shows filmed in Los Angeles, agreed to a new labor contract with the International Alliance of Theatrical Stage Employees, which represents Hollywood studio teachers. For years, Rocart hired nonunion studio teachers through OLE, classifying them as “independent contractors.”

While OLE’s role in Los Angeles dwindled, its business elsewhere grew rapidly as states like Georgia and New Mexico — where producers are free to hire nonunion teachers — lured film productions with tax credits and rebates.

As OLE grew, so did concerns among some parents and teachers that it was putting its business interests above those of young actors.

“They’re getting a handsome fee from production, providing a teacher. And yet, if there’s an issue that production has caused, they don’t back up the teacher in that situation because it’s biting the hand that feeds them,” said Justin Gross, a studio teacher who has worked for OLE.

Gross said there were occasions when OLE failed to support him while advocating for child actors, including on the Illinois set of an Amazon series “Paper Girls” in 2021. According to Gross, he pushed back against the production’s attempt to disregard labor laws regarding the “banking” of school hours when school was not in session in order to allow his two teen actors to adhere to a robust filming schedule.

Amazon declined to comment.

Simon, the president and founder of OLE, declined to be interviewed or respond to specific questions from The Times.

In a statement he cited an “agenda to discredit the reputation” of his company.

He added: “On Location Education is a leader in the field of educating and providing welfare for minors who work in the entertainment industry. At the forefront of our mission is a concern for the minors’ academic well-being and safety on the set and a commitment to thoroughly understanding and upholding the laws and regulations concerning minors in entertainment.”

Anne Henry, co-founder of BizParentz Foundation, a non-profit that provides educational resources and advocates for child entertainers and their parents, says that more accountability is needed on sets.

“I think there needs to be more responsibility taken by the people involved,” Henry said. “Frequently, directors and producers don’t have much experience working with children and they do things that they would do with adults. It’s not until something happens that they realize that it’s not right.”

Problems on the set of ‘Stranger Things’

Four teachers who worked for OLE on the hit Netflix series “Stranger Things” during filming in Georgia alleged child actors were not properly supervised on multiple occasions, including during extreme scenes in which wires and ropes were used.

SAG-AFTRA’s contract stipulates that when filming outside of California, production companies agree to comply with the union’s rules surrounding minors — including that teachers should be informed when children are involved in stunts or physical activities.

Further, OLE’s employment contract, viewed by The Times, states that teachers are responsible for “caring for and attending to the health, safety, and morals of the Children in the same manner as a teacher in a traditional classroom setting.”

However, three of the teachers said they were discouraged by OLE from watching the kids when they were acting on set while they worked during the first three seasons of the show.

“I was told that all I had to do was just stay in the trailer and wait for the kids to be brought in to be schooled,” said one teacher who declined to be named out of concern for professional retaliation. After watching the first season, however, this teacher lamented, “There’s a scene where one of the kids is in a water tank. I should have been there.”

In 2018, after the first two seasons of “Stranger Things” were filmed, Georgia established the role of Child Labor Coordinators (CLCs). They are responsible for coordinating safety services around working minors, including on sets. To earn a certification one must be at least 21, pass an online test and watch a short video.

But during filming of the series in 2018, an assistant director who was designated as a CLC stayed at base camp and was not on set when the child actors performed stunts or extreme physical activities, two of the teachers said.

“If the CLC was not on set, who was supervising the kids?” one teacher said.

A spokesperson for Netflix said: “These claims are inaccurate. The health and safety of our cast and crew is our highest priority. We follow every state and guild guideline, work with a variety of safety and child welfare professionals including child labor coordinators, SAG representatives, and with parents and guardians. No complaints have been made. Our sets are safe.”

‘You can’t stop a freight train’

Several former OLE teachers said they were removed after calling out potential safety problems and other concerns.

Dimond said that she had been let go from two productions after conflicts over upholding labor laws for the child actors on set.

The first incident was in March 2019, while she working as a teacher and a CLC on an NBC pilot.

Problems arose, she said, when an assistant director wanted to extend the set time for twin 4-month-old babies by an hour beyond the two-hour limit required under both Georgia labor laws and SAG-AFTRA rules.

“There are strict parameters with babies,” she said.

Before signing off on the request, Dimond asked if the Georgia Department of Labor had approved a waiver for the extended time. The assistant director said a verbal consent was given.

Concerned about the absence of written waivers, Dimond turned to OLE for support.

“You will just need to let them do what they choose to do. You can’t stop a freight train single-handedly,” an OLE vice president wrote in a text to Dimond viewed by The Times.

Dimond said she eventually received the waivers, but only 15 minutes before the babies’ allotted time ended.

Hours following the exchange, OLE informed Dimond that she would not be returning to set, even though she said in texts reviewed by The Times that she was scheduled for another week and had already booked and paid on her own for a hotel, an expense for which she said she did not get reimbursed.

“I was very upset about it and I didn’t get to say goodbye to the kids,” she said. “We are independent contractors. And so we can lose our jobs at the drop of a hat with no reason or excuse given.”

A spokesperson for Universal Television declined to comment.