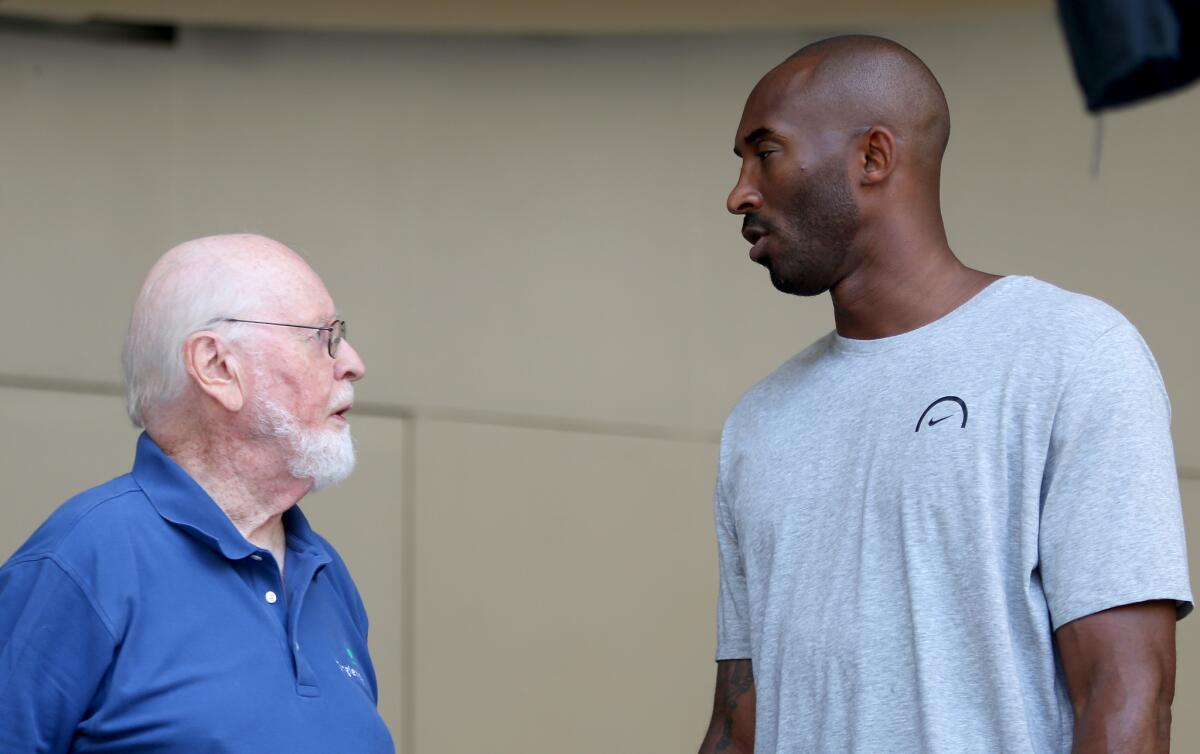

Just before the 2008 basketball season, Kobe Bryant, the 18-time NBA All-Star, called up John Williams, the five-time Oscar-winning composer, for some advice.

“I asked myself a question,” Bryant said. “What makes a John Williams piece timeless? How is he using each instrument? How is he building momentum? As a basketball player, what I found myself doing a lot was essentially conducting a game, right? I wanted to talk to him about how he composed music, and try to find something similar that I can then use to help my game as a leader and winning championships.”

Williams was, understandably, surprised.

“The first thing I told Kobe was, I’d never seen a basketball game,” Williams said. “High school, college, professional, or television. And of course he laughed.”

Bryant had another motive for meeting: He wanted a picture with the composer to show his daughters.

“‘Hedwig’s Theme’ [from the “Harry Potter” movies] puts Natalia to sleep, that has put Gianna to sleep, and now it puts Bianka to sleep,” he said, admitting that as a boy he ran around to Williams’ “Superman” theme with a towel around his neck. “I lay them on my chest and I hum it to them, and the vibrations of it just relaxes them.”

The first thing I told Kobe was, I’d never seen a basketball game. High school, college, professional or television. And of course he laughed.

— Composer John Williams

The unlikely pair continued to see each other backstage at Williams’ concerts over the years, and when Bryant decided to produce a short animated film based on his “Dear Basketball” letter — written for The Players’ Tribune in 2015, when Bryant announced his retirement — he wanted one person to score it.

Williams premiered the five-minute piece during his annual program of movie music Friday night at the Hollywood Bowl, and Bryant made a surprise appearance. He narrated while Williams and the Los Angeles Philharmonic accompanied the film, a performance repeated Saturday and Sunday nights.

Bryant recalled that the first thing Williams said to him was, “I do classical pieces, and it’s all by hand.” Bryant replied by saying, “The piece will be hand-animated by Glen Keane, who is you in the animation space. I want it to have the human touch. I don’t want it to be poppy, I don’t want it to be hip-hoppy. I want timeless, classical music.’”

Keane was a veteran animator at Disney who designed and animated Ariel in “The Little Mermaid.” He was equally surprised to receive a phone call from Bryant.

“When he came over to my little studio here, it was so magical,” Keane said. “There’s 20 years of separation between Kobe and me, and me and John — there are three generations of people there. But each of us, I think, just felt a little bit like a kid that absolutely loves what they do.”

How is he using each instrument? How is he building momentum? As a basketball player, what I found myself doing a lot was essentially conducting a game.

— Kobe Bryant, drawing parallels between his goals as a basketball player and John Williams’ work as a conductor

SIGN UP for the free Essential Arts & Culture newsletter »

Using graphite on paper, Keane illustrated entirely by hand the arc of Bryant’s letter — from little Kobe tossing rolled-up tube socks to NBA glory to retirement at 37. Keane went to Japan to find just the right pencil, settling on the same ones used by animation master Hayao Miyazaki.

Williams, too, draws with pencil and paper, composing at the piano in his living room and notating every instrument in the orchestra.

“Composing the way I do is a very labor-intensive thing, because I don’t have synthesizers and computers and so on,” Williams said. “I’m doing it all by hand — which is a medieval practice, to say the least.”

Keane refers to drawing as “seismographs of my soul. It registers emotions that you are drawing. And certainly John is doing that as he’s writing out the score.”

Williams wrote and recorded the short score — his first for traditional animation — as “a gift” for Bryant in March, taking a two-week break from work on the forthcoming “Star Wars: The Last Jedi.”

“Dear Basketball” is part elegy, part love letter, and Williams composed a bittersweet melody that swiftly runs through a range of emotions.

Bryant heard the music for the first time with full orchestra on a Sony scoring stage.

“Oh my God,” he said. “I almost lost my mind. As soon as his hands went up and then the music started, I almost yelled out loud — but I had to remember that the red light was on and we’re recording.”

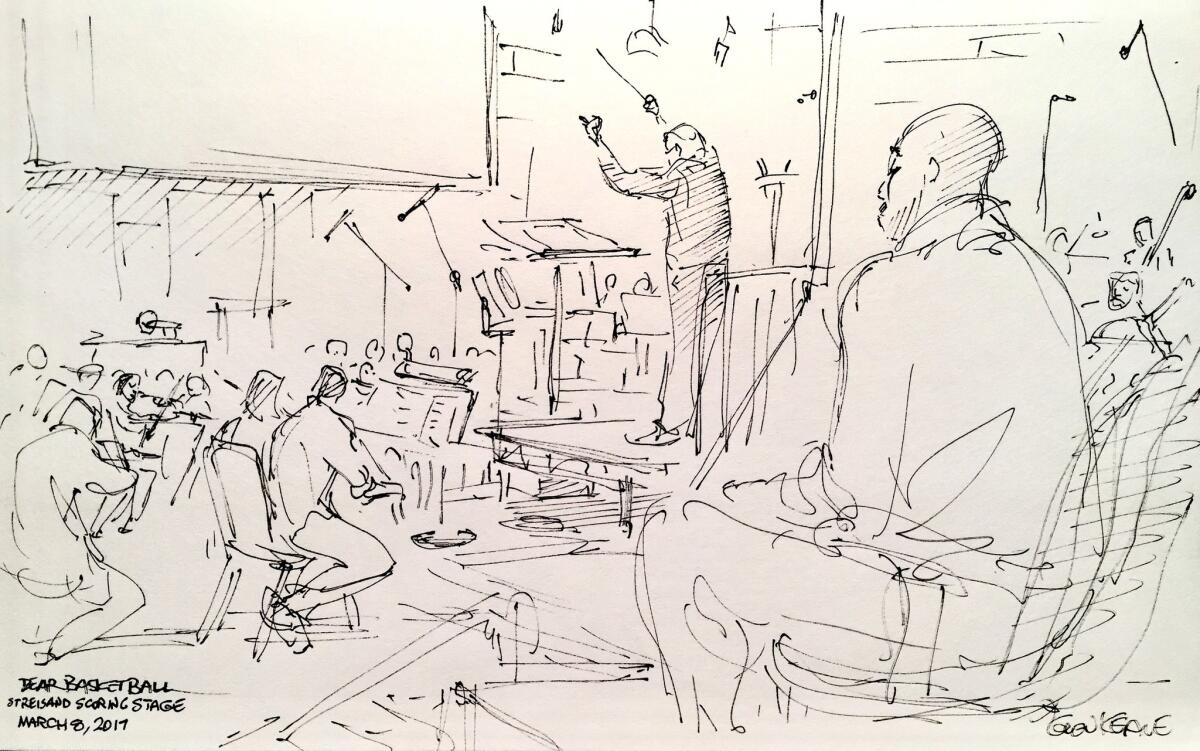

Keane drew a sketch to capture the moment.

“Kobe’s got his eyes closed, and John’s standing there in his very unique, John way,” Keane said. “There was such a dignity of him, and the way he placed his feet so close together, and stood there with his arms up — I tried to capture all of that in this sketch of this master kind of holding the orchestra in his arms.”

Since retiring, Bryant has poured himself into outlining stories, which his Granity Studios is developing for a variety of media. He hopes to hire the composer again.

Williams “has been a part of our family for so many years, without even knowing,” Bryant said. “So to actually have a piece that he composes on something that I have written, and to see him do it there with the orchestra … it was the most unreal experience I could ever have.”

Support coverage of the arts. Share this article.

MORE FROM THE ARTS TEAM:

ICA LA: A sneak peek inside downtown’s new art museum

Muralist Robert Vargas is painting a towering history of L.A. above the traffic

The 99-seat beat: Carl Weathers, hidden figures and political warfare hit L.A.’s small theaters