When Shirley Alvarado del Aguila got to work on Jan. 27, she told colleagues she didn’t want to talk about Kobe Bryant, who had died the day before in a fiery helicopter crash, along with his 13-year-old daughter and seven others.

She was frustrated that the basketball star was being lionized by a public that seemed to forget he’d been arrested and accused of rape in 2003. She works for an organization that serves rape and domestic violence survivors, and she was angry that people who brought the subject up were being attacked online. So she deactivated her social media accounts.

She also worried about the woman who said Bryant had assaulted her nearly 17 years earlier — what she was thinking, how she was holding up.

The NBA star denied the rape allegation, saying the sex had been consensual — although he understood the woman felt differently. Felony charges were filed, only to be dropped after the woman declined to testify. Through the years, and in the wake of his death, his ardent fans have chosen to focus on his achievements on and off the court.

But in the week since Bryant’s death, a chorus of women and men has taken to social media to say they feel alienated and worried that an important element has been omitted from the narrative growing around the beloved Los Angeles Laker. They believe that ignoring the alleged 2003 assault does a disservice to all sexual assault survivors — and one in particular, the woman who said he attacked her.

Alvarado del Aguila, who was sexually abused as a child and encountered sexual violence later in life, acknowledged that Bryant’s death brought up diametrically opposed emotions. On the one hand, she said: “I feel for his family. I can’t imagine what they’re going through. Someone has died, and all of us are allowed to process and grieve in our own way.”

But she added: “Survivors need to make sure our stories are not erased again and again to lift up powerful men’s legacies.”

Through her attorney, the woman who pressed charges declined to comment following Bryant’s death. She does not speak publicly about the events that upended her life. Over the years, she has been maligned and threatened.

A Swiss bodybuilding coach who allegedly offered to kill her for $3 million was charged with solicitation to commit murder, among other crimes. After several charges were dropped, he pleaded no contest to grand theft and was sentenced to three years in prison.

An Iowa student who left death threats on her answering machine was sentenced to four months in prison. A Long Beach man accused of sending 70 obscenity-laced death threats to the woman and the prosecutor in the case was sentenced to nine months in a federal prison camp.

Patricia Giggans, executive director of Peace Over Violence, the longest-running sexual and domestic violence hotline in the country, said she would never forget the assault charge brought against Bryant and the vitriol it animated in some fans.

“That young woman was vilified in the media and in fandom,” Giggans said. She worries that women who speak up today run the risk of similar rancor, or worse.

In fact, said Stacy Malone, executive director of the Victim Rights Law Center, if society does not include this “credible allegation” of rape as part of the Bryant narrative, it risks contributing to the silencing of victims.

“And aren’t we taking a step backward?” she asked.

In the years since the rape allegation, and especially since he retired from playing professional basketball, Bryant became an advocate for women and a proponent of women in sports. Fans worldwide have mourned his death, flooding the streets around Staples Center with flowers, posting tributes, sharing their grief, painting murals in his honor.

But the debate goes beyond one basketball player.

There’s often a tension around celebrities who have complicated pasts, especially when it comes to those accused of domestic violence or sexual assault, said Dana White, a survivor of sexual assault who works with a national youth-focused LGBTQ organization. There’s a balance between showing respect for those who died, White said, and caring for and supporting survivors.

“The ability to hold multiple truths about anyone, whether it be a celebrity or someone we were personally connected to, is an act of love and respect, to be able to see a person for all of who they were,” White said. “I think that accountability, on the other hand, is a broader love and respect for the community. We have to do both.”

Just as survivors are not synonymous with what happened to them, said Savannah Shange, an assistant professor of anthropology at UC Santa Cruz, Bryant should not be reduced to the harm he allegedly caused. His potential for transformation and growth should be weighed along with his shortcomings, she said.

Shange pointed out that Bryant had apologized to his accuser. “An apology is not enough, but it’s the beginning of the process of accountability,” she said. “And it is important to acknowledge that Kobe gave us an example of what starting that looks like.”

In the aftermath of the deadly crash, social media lighted up with conflicted feelings, of sympathy and grief but also pain and anger.

@abroshar tweeted about how Bryant’s death had been “painful in so many weird ways.” She wrote about the day she met the daughter of the man who had raped her, about how sweet the girl was and how much the rapist loved his child.

“… all I could think was ‘look how different he is with people he values,’” she wrote. “What am I supposed to do with this?”

In the lengthy thread, @deedropsbeats said Bryant’s death saddened her but that she also was thinking about the woman who accused him of rape. “Is it because Kobe made an official apology to the accuser and the people he hurt,” she wrote, “… that people quickly forgave and moved on?”

And then there was Disney heiress Abigail Disney, who ignited a furious response when she tweeted Wednesday: “I haven’t said anything about Kobe so far because I felt some time needed to pass before weighing in. But yes, it’s time for the sledgehammer to come out. The man was a rapist. Deal with it.”

John-Lancaster Finley, a policy associate with the California Coalition Against Sexual Assault, sees Bryant’s death through a different lens.

On Facebook, he wrote about how growing up “every little kid (especially the black kids) pretended we were Kobe at some point.”

Finley, who is black and a survivor of sexual assault, said he found any conversation about Bryant difficult and triggering. He said he was struggling to reconcile Bryant’s complicated legacy with what he characterized as a readiness by some to “lynch” the NBA star for his past actions, coupled with an “utter lack of respect” for his grieving family.

“I won’t be mad at anyone who doesn’t want to engage with this,” Finley ended his message. “This is really hard and Lord knows I’m not prepared for it either. But I’m just asking for a little compassion. I’m asking for a little patience and a little kindness. Kobe’s death is hitting me hard and it doesn’t mean I don’t care about survivors.”

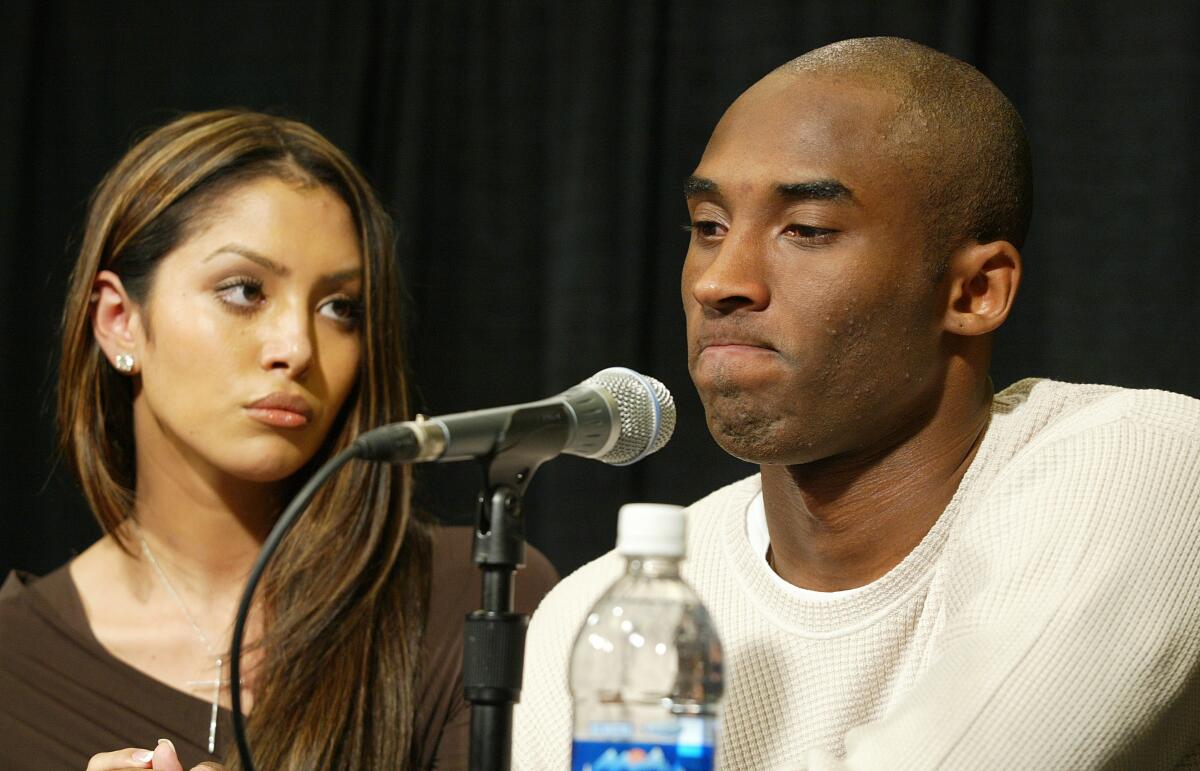

Bryant was 24 and married — to Vanessa Laine Bryant, a model and dancer — when he went to a resort in the Rocky Mountains town of Edwards, Colo., while awaiting surgery. A 19-year-old front-desk clerk gave him a tour of the property and later went to Bryant’s hotel room, where she alleged he raped her.

After charges were dropped in September 2004, Bryant issued a statement that same day:

“Although I truly believe this encounter between us was consensual, I recognize now that she did not and does not view this incident the same way I did,” Bryant said. “After months of reviewing discovery, listening to her attorney, and even her testimony in person, I now understand how she feels that she did not consent to this encounter.”

A civil suit brought by the accuser was settled out of court a few months later.

Professional athletes — particularly male ones — are often deified by the public, said Derek Van Rheenen, an education professor at UC Berkeley who studies the intersection of sports and society.

Sports function like a religion in many ways, he said; fans are like disciples who give all of themselves to a team or athlete. And in a world where the public has lost faith in the political, legal, economic and education systems, sports are an escape. It makes sense that people would be upset that some have dredged up a dark era in Bryant’s life, he said.

Survivors who have spoken out about how they feel in the aftermath of Bryant’s death have been chastised and in some cases threatened, they say.

Heather, a 52-year-old Sonoma County resident, found this out first-hand. That’s why she asked to be identified only by her first name when speaking about Bryant.

When she first heard about the crash, Heather said, she felt as if the breath had been knocked out of her. She also thought of his family and the unspeakable grief she endured when her own sister died unexpectedly. She thought about the woman who said Bryant had raped her.

Heather was sexually assaulted three decades ago. She endured the grueling process of taking her attacker to court. He eventually pleaded guilty to criminal sexual conduct.

The night of the crash, as she flipped back and forth between TV networks in her living room, she said she heard reporters use the phrase “he had his ups and downs” to describe Bryant’s life.

“I just could not stop thinking: How is that a euphemism for alleged rape?” Heather said.

She tweeted about how such a description “minimized” the woman’s experience. The menacing responses began almost immediately.

As she sat alone the night of Bryant’s death with just her dogs for company, Heather said, she was overwhelmed with grief.

And she cried.