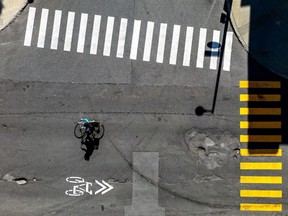

Confusing, obscure, just plain wrong: As bus lanes and bike routes expand across the city, so do head-scratching pavement markings.

The ground seems to be talking more than ever to drivers, cyclists and pedestrians amid the expansion of bike routes and bus lanes and heightened safety concerns.

But do road users understand what all the yellow, white, green and blue messages painted on the asphalt are telling them? Not likely, experts say.

Municipalities and boroughs “don’t make a good enough effort to say what they mean,” observes Oren Preisler, an instructor and manager at family-owned Morty’s Driving School.

Preisler has had a front seat view of the evolution of road markings while supervising learners on practice drives over the last 20 years. His observations: some symbols are vague or ambiguous; not all are consistent across Montreal Island even though markings, like road signs, are standardized by the province; and many types of markings are never accompanied by an explanatory road sign, which is paradoxical since Quebec’s provincial roadwork manual states that pavement markings exist to reinforce road signs.

There’s also a problem with barely discernible markings, Preisler added. Some public authorities don’t act quickly enough to repaint them after winter’s harsh treatment, he said.

One example of a road marking that has cropped up with no explanation of its subtleties is the yellow zigzag. Can a moving car that’s preparing to make a right turn drive over a yellow zigzag in the right lane, or does the car have to make the turn from the middle lane to avoid the zigzag?

If you guessed the second option, give yourself an imaginary demerit point.

The Société de transport de Montréal explains that yellow zigzags are painted next to bus stops that intersect a bike lane and their purpose is to alert the cyclist to the presence of the bus stop. With or without the symbol, motorists aren’t permitted to stop at a bus stop. And unless it’s otherwise prohibited, motorists are legally obligated to make a turn from the lane that’s closest to that side.

It’s unlikely that motorists who passed their driver’s test years ago will know all the rules associated with some newer pavement markings because the symbols are not all intuitive, agrees Nicolas Saunier, a professor of transportation engineering in Polytechnique Montréal’s department of civil, geological and mining engineering. He’s an expert in road signage and markings.

“There’s no obligation to keep up to date or receive training on the road,” Saunier said of veteran drivers. Moreover, a cyclist, scooter rider or pedestrian who never got their driver’s licence will not have learned about pavement markings and road signs in the one place where that sort of thing is taught: driver’s ed.

“The reality is we don’t know who knows what,” he said.

An example of a confounding pavement marking can be found on the reserve bike lane on either side of Laurier Ave. in Outremont. The lane is demarcated by the standard solid white line, but the lane is also dissected lengthwise by an off-centre broken white line that leaves even an expert like Saunier stumped about its purpose.

He sought answers from the borough and the city. The Gazette got the answer from Vélo Québec because the former City of Montreal traffic engineer who conceived the symbol on Laurier now works for the cycling advocacy organization.

The broken white line along the outer edge of the Laurier bike path was a pilot project in 2019, and it was meant to show cyclists how far the door of a car parked between the bike lane and the curb will reach if it swings open.

But the usefulness is lost if no one knows what the symbol means, said Saunier. “I had a feeling it was an error that just kept being repainted because the painting crews follow what was already on the ground but faded.”

Clear communication of the rules is an important safety issue, especially for vulnerable users of the road, Jean-François Rheault, president and CEO of Vélo Québec, said.

Montreal’s cycling facilities, which is a general term encompassing bike paths and bike lanes, rely on pavement markings to show direction, where to stop and turn and where bikes will intersect with vehicle traffic.

“Road marking is very important when it comes to cycling because much of the bicycle infrastructure is painted lines,” Rheault said. “If the marking isn’t in good condition or isn’t appropriate, then the safety of the infrastructure disappears. So it’s important that it’s done well, but also that it get better and better.”

One of his concerns is insufficient road marking along contraflow bike lanes, which are painted lanes on one-way streets that require bikes to ride in the opposite direction of motor vehicle traffic.

For example, the contraflow bike lane on Clark St., between Rachel St. and St-Joseph Blvd., has a bike and arrow symbol painted on the ground at the ends of each 200-metre-long block to indicate that bikes travel south while motor vehicle traffic is one-way north. But between intersections, there’s no marking or sign to warn a driver who’s pulling out of a garage, alley, parking lot or parking space and cutting across the bike lane that cyclists will be coming from the driver’s left, in the opposite direction of the cars coming from the right.

“A contraflow bike lane is typically one type of infrastructure that is not well understood,” Rheault said.

“In Quebec, we don’t put a lot of symbols on the contraflow.”

Some other provinces require bike pavement symbols to be placed every 100 or so metres, he noted.

The opposite problem exists on some Montreal streets that have a ton of pavement symbols and signs, but few people seem to understand what they mean.

The “Vélorue” (“Bicycle Route” in English) presents such a communication challenge. The Vélorue was introduced in a 2018 update to the Quebec Highway Code and has a low speed limit and its own set of traffic rules. For example, bikes and cars share the middle of the road, and two bikes are permitted to ride side by side.

Municipalities are responsible for designating streets as Vélorues, and Montreal has so far created nine of them, including Villeray St., from St-Laurent Blvd. to St-Denis St.

“In this case, it’s very important that road markings are in very good condition,” Rheault said. Except that they’re not. The province’s standardized yellow road sign for the Vélorue — diamond-shaped and showing two cyclists side by side — says nothing to someone who isn’t familiar with the Vélorue and its special traffic rules.

Meanwhile, one ubiquitous pavement symbol is at risk of losing its intended meaning as it becomes a catch-all. Montreal seems to love the white bike topped with two white chevrons so much, it’s painting the symbol all over some intersections like a street art installation.

But according to the Quebec roadwork manual, the bike with two chevrons has specific functions. It’s supposed to be used in a bike lane delineated by a white solid line to indicate the direction of bike traffic. It can also indicate a major change in the direction of a bikeway. And painted on the road without the solid white line, it’s a “sharrow” — or “shared arrow” — indicating that cars and bikes share that road.

The multiplication of painted markings has its downside, Saunier said.

“We have an increase in all these things and what it does is to make it more complex to read and understand the appropriate behaviour in these different situations,” he said. Safety is a concern, Saunier said, but bombarding road users with visual rules “is a somewhat magical belief that if we put up more, it’ll solve the problem.”

The intersection of Laurier Ave. W. and Côte-Ste-Catherine Rd. is an example of a cacophony of symbols, he noted. It’s festooned with a white grid containing two smaller boxes that each contain a bike symbol and two chevrons, plus left-only and right-only arrows, a reserve bike lane symbol, a T-shaped green bike box, a crosswalk and other markings.

When we’re busy looking out for the many signs and symbols telling us how to behave, Saunier said, “we forget a bit to just interact, to be very attentive and to take the time to look at the traffic around us and the users nearby.”

Some cities in the Netherlands and England have gone in the opposite direction and are experimenting with removing road signs, pavement markings and traffic lights, he said. It follows Dutch traffic engineer Hans Monderman’s approach of “shared spaces.” Monderman, who died in 2008, emphasized that common sense and good road design rather than signs and markings should cue users on how to navigate and adapt behaviour.

Quebec isn’t ready to strip away markings and signs, Saunier said, noting the province is still in a phase of making roads more inclusive of pedestrians and cyclists. However, he predicts that adding markings will eventually reach the point of diminishing returns.

From Preisler’s vantage point, it would be useful if boroughs and municipalities on Montreal Island were at least consistent with their road symbols.

Some discrepancies are relatively benign, like speed bumps adorned with yellow arrowheads in some communities while they’re bathed in yellow paint in some others.

But inconsistencies can create confusion, Preisler said. Think of bike lanes that are delineated by a single solid white line while others have double solid white lines and still others incorporate diagonal lines.

“Some are faded out, some are not,” he added.

And although the roads are talking more, Preisler notes that Quebec places little emphasis on teaching road symbol literacy.

Since 2010, learners are required to attend an accredited driving school to get a driver’s licence in Quebec. They must first take five mandatory two-hour classes then pass a test to obtain a learner’s permit so they can practise in a car. But Quebec’s suggested curriculum for the five classes doesn’t cover road signs or markings, Preisler said. Morty’s chooses to add that material, he added.

“But the onus falls on the student to go and study it,” Preisler said. “You wouldn’t want to start driving around unless you’re 100 per cent sure of what you’re doing on the road.”