Author, photojournalist and former Calgary Herald journalist David Bly wrote and photographed the historical content about ghost towns, republished below, originally in September 2005. While the attractions and population numbers in these places have fluctuated since then, they still retain a sentimental appeal for many.

Ghost Towns: The urbanization of Alberta has left the rural landscape dotted with communities that progress has passed by

By David Bly

There was a time when small-town life defined Alberta, when most Albertans lived in or around communities where they knew their neighbours, where the community supplied social, physical and spiritual needs.

Yet many of those towns no longer exist, or have dwindled almost to nothing, victims of climate, economics and progress that brought quick access to larger centres and depopulated rural areas.

Like the stubborn caragana bushes that still grow around abandoned homesteads, some communities continue to exist, and even grow a little, as people discover the peace and neighbourliness of places that city dwellers might see as impossibly small.

But it can be a melancholy journey driving past the ghosts of dead dreams, of abandoned places that were once called home.

Here’s a glimpse of four places that many people have forgotten, but some still cherish.

ROWLEY

Population: 6

Progress passed Rowley by, leaving it in the past. And that’s its future. Its train station is still intact. It has three elevators standing in a row. Its streets and houses have changed little in two or three generations, making it an ideal spot to make period movies.

That’s what Anne Wheeler thought when she used Rowley as a set for Bye Bye Blues, a film about a young Canadian woman facing a choice between a singing career and loyalty to her husband, who is in Europe fighting the war.

More recently, this community 25 kilometres north of Drumheller posed as rural Colorado in The Magic of Ordinary Days, a Hallmark movie about a pregnant city woman sent by her father into a marriage with a farmer who is not the father of her child.

The movie, which garnered positive reviews, stars Keri Russell.

Several commercials have been shot here and more are likely to come, says Doug Hampton, the community association president and the closest thing Rowley has to a mayor.

Hampton was raised on a farm a couple of kilometres from town, and moved here around 1980.

“I’ll probably die here,” he says. “It’s a peaceful place. No traffic, except in the summer, when the tourists come through.”

One carload of travellers can double the town’s population, he says.

The community association owns and maintains most of the buildings in the town, including the grain elevators.

It’s a huge challenge to look after the elevators, says Hampton.

“They need new roofs and a paint job,” he says. “It takes a lot of money to fix those suckers up.”

Maintaining a town as a living museum wouldn’t be possible without the volunteers, he says, people who live on farms in the surrounding area and in the nearby communities of Morrin and Rumsey.

The community comes together the last Saturday of each month for pizza night in the saloon.

Want to rent a town for your next party?

“Yeah, we can do that,” says Hampton. “We’ll fix the food and everything.”

Rowley never had more than a couple of hundred people at its peak, says Hampton’s sister-in-law, Lucille. But it still serves as a centre for the area — she runs the post office, which has 16 box-holders.

WAYNE

Population: 31

“Welcome to Wayne,” says the sign. “Population: then 2,490, now 42.”

That’s an exaggeration, says Fred Dayman, owner and operator of the Rosedeer Hotel (est. 1913) and its adjacent Last Chance Saloon. “It’s more like 31.”

At one time, Wayne was bigger than Drumheller, its population employed by the 10 coal mines that operated in the area. When coal’s reign ended, the town was all but abandoned, some of its buildings moved, others left empty. “We had our choice of playhouses,” says Dayman, who was born and raised in Wayne.

Twenty-two years ago, he bought the hotel and saloon from his mother, and hasn’t been shy about exploiting the town’s Wild West look. The saloon’s decor is made up of every western cliche you can think of, and is just downright fun.

The burgers are hot, huge and hearty and the beer comes in quart sealers, if you’re so inclined.

Wayne, though a fraction of its former size, is far from dead. It bustles in the summer as tourists come to soak in the historic atmosphere and the scenic valley of the Rosebud River.

On the second weekend in July, the town’s population grows to 4,000 as bikers roar in for a Harley-Davidson rally. And in September, visitors flock to Wayne for the annual music festival: country, bluegrass, “a little bit of everything,” says Dayman.

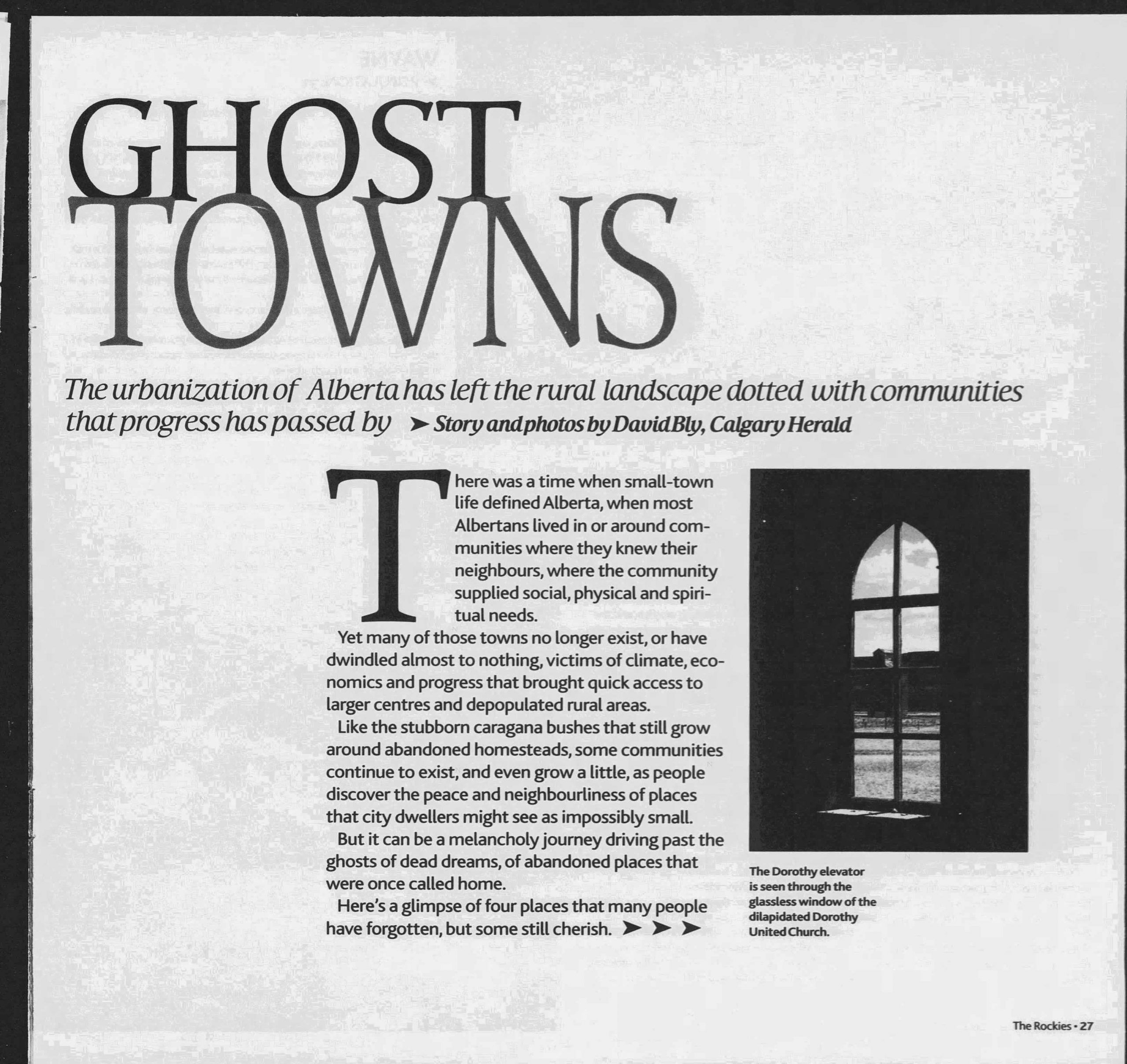

DOROTHY

Population: 13

Ray and Betty Faubion got some teasing when they retired from farming and moved to town.

“When we were planning to move, one friend said Ray had been working in the sun too much,” said Betty.

They could have gone another half hour up the road and lived in Drumheller, which has all the amenities anyone would need.

But they chose Dorothy, with its handful of houses, two derelict churches and an abandoned elevator sitting along the Red Deer River.

“It’s beautiful here,” says Betty.

“We can see everything up and down the valley. We can hear the birds . . . the meadowlarks, the goldfinches.”

“And the taxes are $400 a year,” says Ray.

They haul water to irrigate their yard, but their potable water comes from a spring, courtesy of a neighbour.

“When we moved in, he hooked us up to the water. Did everything; wouldn’t take anything for it,” says Ray. “He says we could do something for him sometime. That’s the way it is here.”

At its peak, Dorothy had about 150 residents, three elevators, three stores and three gas stations.

It enjoyed a brief period of international fame when the Toronto Star published a story by Richard Harrington in 1951 about all the lonely rancher bachelors of Dinosaur Valley.

The story was picked up by Parade magazine in New York, and by European publications. The small Dorothy post office was flooded with cards and letters from willing women, and the postmistress passed them out to any male who was remotely interested.

Parade magazine even flew in one of the letter writers, Rose Brewer of Chicago, to meet Tom Hodgson, one of the bachelors, hoping to cash in on a story of a big city girl falling in love with an Alberta rancher.

“She stayed with me,” says Blanche Hodgson, 87, Tom’s sister-in-law. “She was a very nice girl, a very decent girl, but she had no notion of coming here to get married. She likely came for the trip.”

A friendship of sorts developed with Tom, but not a romance. Rose returned to Chicago and married her boyfriend there.

Although some of the bachelors later married, not one marriage resulted from the thousands of letters that poured in. Tom Hodgson, who has since died, never married.

“It put Dorothy on the map, and it was a lot of fun,” says Blanche. “We still laugh about it.”

ALDERSON

Population: 0

When historian David Jones wanted to tell the story of the ill-fated settlement of Alberta’s dry southeast corner, he focused on Alderson, west of Medicine Hat, along Old Highway 1.

Surveyed by the CPR in 1910, the town, then called Carlstadt, grew quickly. (The name was changed during the First World War because people thought Carlstadt sounded too Germanic.)

By 1913, its businesses included two general stores, three lumber companies, three insurance and real estate offices, two implement dealers, two hardware stores, two pool halls, two churches, a drugstore, a meat market, a bakery, a Union Bank, a two-room school and five hotels.

But that was its peak. As the First World War raged, Alderson began to dwindle, a victim of drought, fires and the harsh reality that the prairie could support only so many people. By the early 1920s, most of the people and businesses were gone.

Today, one small shack is the only building left standing amid the crumbling foundations.

In the spartan cemetery 100 metres to the east, the leaning tombstones of a dozen graves stand as monuments to a lost way of life.

“Alberta is so urbanized with two major centres dominating,” says Jones. “You ask people where these towns are, and they don’t know.

“It’s the old-timers, the folks on their way to heaven, who remember that way of life.”

***