Hi, and welcome to another edition of Dodgers Dugout. My name is Houston Mitchell. We interrupt the postseason with a sad newsletter.

Are you a true-blue fan?

Get our Dodgers Dugout newsletter for insights, news and much more.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

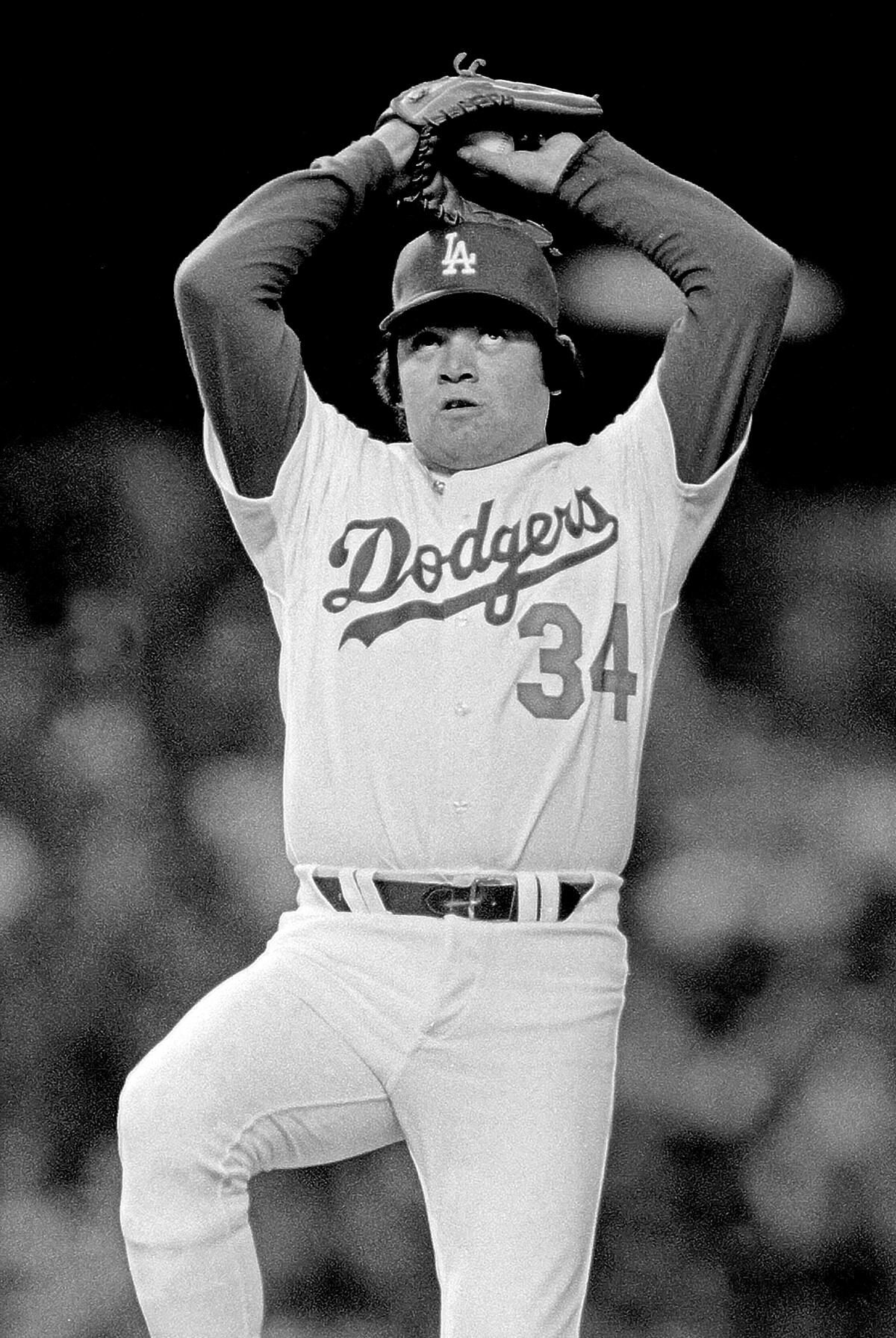

Fernando Valenzuela started pitching for the Dodgers at the end of the 1980 season, and even though I attended all three season-ending games against the Houston Astros at Dodger Stadium and he pitched in two of those, I sadly don’t remember his appearances at all. When historic moments begin, we often aren’t aware of it.

Fernando (and he’s Fernando. Calling him Valenzuela just feels wrong) really became famous after his amazing start to the 1981 season. I was attending Carnegie Junior High (what you kids call middle school now) in Carson. To say Fernando captured the imagination of most of the student body is an understatement. The Lakers weren’t quite the big deal they would become later and the Dodgers were the prominent team in L.A.

Enjoying this newsletter?

Your support helps us deliver the news that matters most. Become a Los Angeles Times subscriber.

Carnegie had a very ethnically diverse student body, and Fernando united all of us. If he was pitching in a day game, a couple of people would bring a radio and we’d listen to the game. Maybe, just maybe, there were a couple of spots on campus where you could hide and listen to the game rather than attend class. I neither confirm nor deny those reports.

If he pitched a night game, we would discuss it the next day. Other kids you didn’t know would high-five you if you were wearing Dodgers gear.

Carnegie’s open house, for parents to go from class to class to meet their kid’s teachers, was held at night. Unfortunately it was a night Fernando pitched. Open house was sparsely attended and the next day school leaders couldn’t figure out why. (Adults are always the last to catch on to what’s cool.)

Somehow, and I don’t remember the impetus for this, I wrote a poem about Fernando. The poem was titled “Fernando, the Great Valenzuela.” The only verse I remember is this:

Fernando, the great Valenzuela

A little boy in Mexico thought baseball might be fun

So Fernando, the great Valenzuela

Started pitching for the Dodgers and now he’s No. 1

That’s poet laureate-type stuff. Yes, I know, pretty terrible. But I was 13 at the time. I showed it to a couple of friends, and it quickly seemed everyone in the school read it. A student band turned it into a song and won the school talent contest. It was published in the end-of-year magazine of the best writing of the year. People (OK, girls) who never looked my way before suddenly were talking to me. Maybe this writing thing was a pretty good path to follow.

Four years later, I was a student at Banning High in Mr. Tattu’s English class. Mr. Tattu is one of the great teachers of all time and every student loved the guy. He had us all write weekly essays on any topic and gave them a score of 1-10. No one had received a 10 in three years. Each Monday, we rushed into class and looked in his grade book to see if anyone got a 10. Week after week passed. No 10s. One week I wrote an essay about Fernando. It was about the joy of a multicultural experience in the stands during games he pitched.

Students rushed into Mr. Tattu’s class, like usual. Someone got a 10! It was the Fernando essay! And my writing career was confirmed.

So, it’s possible this newsletter wouldn’t exist without Fernando. Now you know who to blame.

Going to Dodgers games when he was pitching was a joy. It was a party atmosphere. But not the party atmosphere of today, with some people drinking too much and some obnoxious people ruining it for the majority. It was a party for everyone to laugh, have a good time and get ready to see Fernando. Everyone was happy after the game. We all looked out for each other, all united by two things: the Dodgers and Fernando.

Fernando is one of the last Dodgers to have the Koufax-like mystique about him. He didn’t speak much English (though some say he spoke more than was assumed). His personal life, even in his later years, was private. Compare how much we know about Orel Hershiser to Fernando.

The other thing about Fernando is he looked like one of us. He didn’t look like an athlete. He looked like a teammate on your slow-pitch softball team. You can identify with that, and let it massage your ego into thinking, “Hey, I could have done that too!”

But actually, Fernando was a world-class athlete who played with the grace of a ballerina. He won one Gold Glove and should have won more. And he could hit, with two Silver Sluggers. He hit .304 in 1990 and finished with a .200 average with 26 doubles, one triple and 10 home runs in his career.

And, Fernando is almost single-handedly responsible for the love the Dodgers receive from the Latino community. There was a time, after multiple Latino families were forcibly removed from their homes in order to make room for the construction of Dodger Stadium, that many Latinos would not set foot in it. Fernando’s success helped changed that.

Not to mention some of his many great feats with the team:

—He was called up at the end of the 1980 season and had a 0.00 ERA in 17-2/3 innings, winning two games and saving one. Some Dodgers fans always will wonder “What if Fernando started the 1980 playoff game against the Houston Astros?” Even though that wasn’t a real possibility.

—He opened the 1981 season with shutouts in five of his first seven games, giving up only one run in each of his other two starts. That means that in Fernando’s first 80-2/3 innings in the majors, he had an ERA of 0.22. Two of the shutouts came on three days’ rest.

—He somehow held the New York Yankees to four runs in Game 3 of the 1981 World Series despite giving up nine hits and seven walks. It was a complete-game victory in which he threw almost 150 pitches.

—He finished third in 1982 National League Cy Young voting after going 19-13 with a 2.87 ERA and 18 complete games in 37 starts.

—In 1986, he went 21-11 with a 3.14 ERA and an astounding 20 complete games in 34 starts. He finished second in Cy Young voting to Mike Scott of the Astros.

—In 1990, he pitched one of the most unlikely no-hitters of all time, as Fernando was past his prime. It was his final season with the Dodgers, who released him in spring training the following season.

And just think of this: If Fernando started his career in this era, Fernandomania would not exist. He never would have been allowed to pitch one shutout, let alone five in his first seven starts. He probably would have been removed after five innings to protect his arm. And perhaps it would have extended his career, but he wouldn’t be the legend he is. We’ll never know what would have happened. Let’s be glad we got to experience it.

There’s no way to prove it, but in my mind the three people responsible for creating the most Dodgers fans are Fernando, Jackie Robinson and Vin Scully. You still see Valenzuela jerseys scattered throughout the stadium, rivaled this season only by the number of Shohei Ohtani jerseys.

And the Dodgers should feel glad they finally wised up and retired Fernando’s number while he was around to enjoy it. It was long overdue.

Fernando appeared on the Hall of Fame ballot twice, dropping off after receiving only 3.2% of the vote in 2004. He was voted into our “Dodgers Dugout Hall of Fame” in its second year of existence, which, I realize, is not quite the same.

As for the real Hall of Fame, here is what voters are supposed to consider: “Voting shall be based upon the player’s record, playing ability, integrity, sportsmanship, character, and contributions to the team(s) on which the player played.”

I submit that going by contributions to the Dodgers, his integrity and character, that Fernando should have received much stronger consideration for the Hall. He increased the popularity of the game and added untold thousands of new fans. Let’s hope one of the veterans committees takes a good, long look next time he is eligible.

Until then, thank you Fernando for the memories and especially for making that one year of junior high a magical place to be.

Your memories of Fernando

Please share your memories of Fernando, to be shared in upcoming newsletters. Put Fernando memories in the subject line of your email and send to me at [email protected].

Former teammates, colleagues remember Fernando

I asked former teammates and colleagues of Fernando to share some memories.

Tim Leary: Spring training 1988. Fernando, myself, Eric Tracy (Dodgers radio host) and Dr. Paul Hiss (a friend from Santa Monica) went golfing at a Pete Dye-designed course in Vero Beach. The ninth hole is 460 yards, a par four. We all get set to tee off and Fernando sticks his hand out for my driver. A 7-degree loft TaylorMade driver. He then bombs a drive past mine by 10 yards. Close to 300 yards. Fernando is a lefty and he just crushed a right-handed driver 300 yards. Unbelievable but true. PGA Tour golfers can’t do that.

Another memory: In 1989 the Dodgers got pitcher Mike Morgan. Fernando, Mike and I hung out on road trips. So we’re in Montreal down in the subway area browsing in some shops. An older couple probably in their late 70s are talking to each other in French and as soon as they saw Fernando they lit up and were so happy to see him and meet him. It was so awesome to see that Fernando was so so loved and admired even in a French-speaking Canadian city. Fernando is a one of a kind treasure and I love him! Fernando belongs in Cooperstown for his achievements on the field and his impact on the game of baseball. He alone is responsible for millions and millions of Dodgers fans from 1981 to now and forever in the future! His impact is unrivaled in any sport!

Jerry Reuss: When he wasn’t pitching, Fernando loved to play. He developed a lasso from a clothesline and when someone on the bench crossed their legs, he’d toss the rope, hook the foot and pull it down. Everybody on the bench had a laugh. Soon, guys would look for him before crossing their legs. Still, Fernando appeared out of nowhere and caught his prey again.

Ross Porter: Fernando loved golf and our family has hosted a celebrity tournament to fund our son’s nonprofit which assists special needs families. This is the 18th year. I invited Fernando several times, but he had been unable to come, but finally in 2021 and 2023, he participated. We have a dinner and program when the golfers finish their play. Three years ago, as we were about to begin the program, Fernando left his table and walked to where my wife, Lin, and I were seated. He said, “I’m going to have to leave, but I want to thank you for inviting me. It was a great day.” His gesture really impressed me. This shy man had voluntarily shown the politeness to express his gratitude when he could have simply walked out the door. How much he had matured in the 40-plus years since he arrived from Mexico.

Another memory: One night in the days of Fernandomania, he pitched a complete-game victory at Dodger Stadium. I was going to do the postgame interview for our radio network so when he walked off the field, I said, “Fernando, I would like to have you on the postgame show.” He shook his head “No” and went down the tunnel to the clubhouse. I was panicking. Who do I get now? The Dodgers players are all in the clubhouse. Thirty seconds later, Fernando reappeared, walked to where the interview would be done, didn’t say a word, sat down, and we had a wonderful chat without an interpreter. I have no idea what he was thinking.

In case you missed it

Dodgers star Fernando Valenzuela, who changed MLB by sparking Fernandomania, dies at 63

Plaschke: Fernando Valenzuela was the man who connected L.A. to the Dodgers

Hernández: Fernando Valenzuela exuded quiet pride, understated dignity and a high baseball IQ

Photos | Remembering the life of Dodgers legend Fernando Valenzuela

Latino fans recall the importance of Fernando’s Dodgers career

Arellano: The Gospel of Fernandomania: Fernando Valenzuela remains a Mexican American icon

Fernando Valenzuela was a game-changer for the Dodgers, baseball, and Los Angeles

Fernandomania @ 40 – Full Documentary

Column: Why Fernando Valenzuela’s magic should ensure him a spot in the Hall of Fame

Remembering Dodgers legend Fernando Valenzuela | 1960-2024

And finally

Fernando finishes his no-hitter. Watch and listen here.

Until next time…

Have a comment or something you’d like to see in a future Dodgers newsletter? Email me at [email protected], and follow me on Twitter at @latimeshouston. To get this newsletter in your inbox, click here.