‘It’s the worst possible outcome,’ said Calgary Construction Association president Bill Black

The Green Line LRT was a colossal project, touted as the single biggest infrastructure development in the city’s history.

Now, it’s a colossal $2-billion bust, one of epic proportions.

How else can one describe a project that had its provincial funding pulled as it was moving forward, with $1.3 billion already spent — employing about 1,000 people — and another $850 million will be needed to wrap it up.

On Wednesday, some layoff notices began to go out tied to the development’s demise, a day after city council voted to officially wind down the initiative.

“It’s the worst possible outcome,” Calgary Construction Association president Bill Black said Wednesday.

“It’s a significant amount of money spent on exiting — $2.1 billion is about the equivalent of one year’s property taxes for the whole city.”

That’s right, at least $2.1 billion looks like it will be circling the drain, unless parts of it can be reanimated by the province or something unexpected happens in the coming weeks.

That was the grim financial news delivered by Green Line leaders and city administrators as council decided to end the project.

“The money that we have pledged to the Green Line is still there. I would say that we want the Green Line to be as it was initially pitched to us,” Premier Danielle Smith told reporters on Wednesday.

“There’s this thought out there that somehow we’re still in a planning stage. No, we’ve gone beyond procurement. We were already constructing,” project CEO Darshpreet Bhatti said during Tuesday’s meeting.

“The question was asked, is 2.1 (billion dollars) the final number? No, it’s not the final number. It’s the bare minimum that we can think of at this point. It likely will go beyond that number.”

Ugh.

Project-related work was already underway in the downtown, the Beltline and Ogden, and land for the line has been bought.

Cars have been ordered from a Spanish train manufacturer, which was awarded a contract in 2021 to provide a fleet of light rail vehicles.

About 70 contracts will need to be reviewed by what remains of the Green Line team and city legal experts. I imagine there’s the possibility of litigation if businesses decide they’re not satisfied with negotiations on terminating signed agreements.

And let’s not forget, plenty of people have been hired by the city, design and construction firms.

“You have many people who have come from around the world and it took us three years to gather that team. So, you can appreciate when you wind down something, these people and these skills will leave,” Bhatti added.

“I’m just lost (for) words, in terms of how I can even console them, and the situation that we find ourselves in.”

If this all sounds like a nightmarish end for the Green Line, it is.

Regardless of where you stand on the politics or the alignment questions that have swamped the Green Line LRT like a tsunami, this outcome sends out a terrible signal.

“It’s a disastrous situation,” said Black, whose group represents more than 850 companies in the Calgary region.

“It’s uncertainty from an investment standpoint that, arguably, even if you have contracts signed, that changes can be made without warning,” added Calgary Chamber of Commerce CEO Deborah Yedlin.

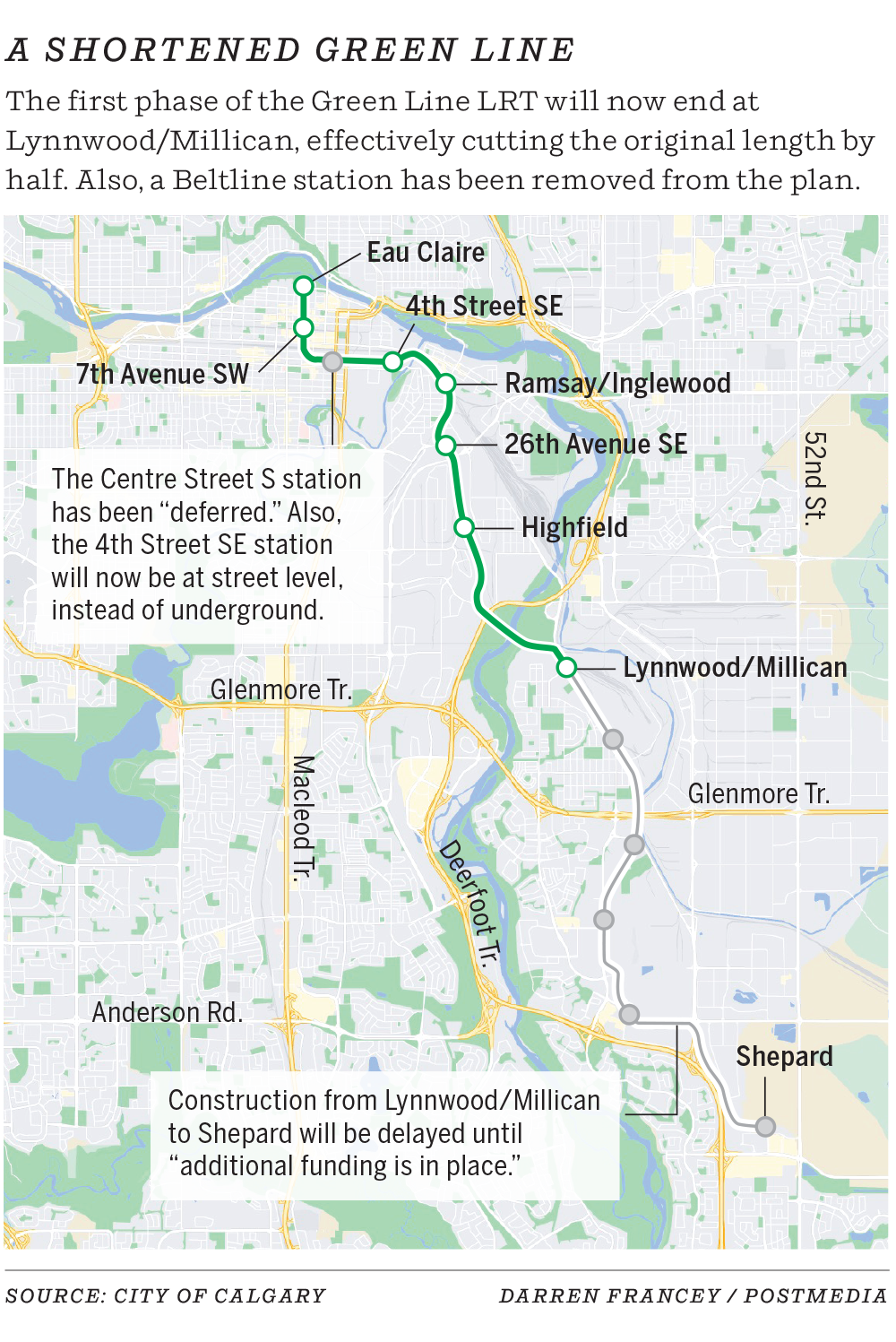

In July, the city announced that the price tag for the first phase of the Green Line had increased by $705 million to $6.25 billion, with its route significantly shortened.

In a letter to the city dated July 29, Alberta Transportation Minister Devin Dreeshen confirmed the province’s $1.5-billion commitment to the Green Line, with certain conditions.

Today, the province wants the LRT line to extend farther southeast to Seton, as was initially planned.

Dreeshen has pointed out the project was first touted almost a decade ago to cost $4.65 billion, and was supposed to extend 46 kilometres and include 29 stations. It’s been condensed to just 10 kilometres and seven stations.

On Wednesday, he said it’s unfortunate some Calgary council members prefer to cancel the project than see an aboveground route that is more cost-effective and longer.

Meanwhile, council wants the province to ensure the city is made whole for its direct and indirect costs.

“Regarding wind-down costs, I don’t see why Alberta taxpayers should be asked to pay for decade-long mismanagements and decisions of past mayors and city councils,” Dreeshen said in a statement.

Setting politics aside, was withdrawing the funding the best — and only — thing to do?

What honest effort was made to negotiate a better solution?

“We have an entire industry that is ready to start on a Green Line now, that is sitting and wondering, what happened?” said Black.

“A lot of mistakes have been made on all sides because of what’s at stake on this project . . . After all this time, after all this drama, it’s done.”

Chris Varcoe is a Calgary Herald columnist.