What began as a plan for a bus-only rapid transit line eventually turned into a full-fledged LRT project before unravelling after more than a decade of work

Council voted 10-5 to stop work and look at ways to transfer management of the Green Line over to the province. The vote landed at the end of a day-long meeting during which municipal officials stressed the city’s vision for the Green Line was not feasible without provincial backing, which was suddenly withdrawn earlier this month.

Planning for Calgary’s Green Line as we know it began in 2011, though the need for a light rail has been under consideration by council since the mid-1980s, according to the city’s Green Line project history.

City explores LRT concept in 2011

In May 2011, around 2,150 Calgarians attended open houses where they explored the concept of an LRT line along Nose Creek, Edmonton Trail or Centre Street N.

“A new planning study determined a route based on a Centre Street N. or Edmonton Trail alignment,” the city noted at the time.

In March 2012, the North Central Planning Study looked into land use planning for transit-oriented development (TOD). This study continued for two years, eventually showing communities would be better served if the North Central LRT was more centrally located.

By December that same year, the Calgary Herald reported on a draft approval of what the city called the RouteAhead blueprint, which outlined transit plans between then and 2040.

“Calgary Transit’s new long-range plan was designed to take the politics out of prioritizing new rail and bus lines,” reported the Herald.

The plan was to began with bus-only lanes in the southeast and along the route down Centre Street or Edmonton Trail, with construction to start in the southeast, but completion on the Centre Street or Edmonton Trail route to be first.

This sparked debates between affected areas of the city, as residents in each believed they should be first to see improvements.

Though the RouteAhead blueprint appeared to be definitive, Shane Keating, Ward 12 councillor at the time, said the real decision would be made when funding actually arrived to build new train lines.

Naheed Nenshi, who began his job as Calgary mayor promising a southeast LRT to Douglasdale as the first priority for transit grants, said the north-southeast debate shouldn’t exist. He pointed out LRT legs would be connected and built in segments starting in 2012 and continuing over the next 28 years.

“We are allowing ourselves to be drawn into a debate where none exists,” Nenshi said at the time. “According to your thinking, it’s all one line,” he told the RouteAhead authors.

Nenshi supported the bus-only lanes, saying a $300-million busway from downtown to the south would shave significant time off current commutes, which was the primary concern heard from area residents. Documents at the time suggested it would save almost as much time as a full LRT would, for about one-tenth the cost.

A lack of money at the time meant the city could only partially start either leg of the north-southeast line until 2022, or fund bus lanes from Douglasdale to north of Glenmore Trail in the southeast, and on Centre Street from downtown to 24th Avenue N.

City feels lack of funding for southeast LRT line, pivots

By June 2013, rapid transit to the southeast had been ranked last in a city study of future transit expansions.

A 2013 cost-benefit analysis of the project estimated the southeast transitway to $108.81/rider, with high redevelopment potential at a total of $642 million overall. It was believed it would cut commutes by 13 minutes.

Nenshi, realizing there wasn’t enough money to fund a $2.7-billion southeast LRT line, began his push for the Green Line approach, which at the time would have seen the southeast and north-central routes developed as a single line.

In October 2013, the Calgary Herald reported Calgary’s relationship with senior levels of government would become critical in the coming years as Nenshi looked to progress the status of the Green Line.

By November that same year — due to a $520-million commitment from city council — transit officials said they would be installing bus lanes and sections of specialized transit roadway piece by piece, in a design meant to shorten an 80-minute commute to 45 minutes.

The $520-million commitment came from a council decision to use the city’s $52 million tax surplus from 2015 to 2024 to fund the Green Line project.

In 2013, it was estimated to cost $760 million to build the entire project, with some of the $520 million going to borrowing costs, so councillors were counting on federal or provincial dollars arrive to fund part of the busway.

The Herald reported in 2013 that a full LRT on the Green Line would cost $5 billion.

In early 2014, Calgary committed to $889 million in transit investments, including the southeast Green Line transit-only roadway and lanes, along the future LRT corridor and the Green Line bus-only lanes in the north.

The city completed TOD background research for the Green Line, including reviewing city policies, North American TOD best practices and conducting a GIS analysis of existing conditions and land use to prioritize site selection. Additionally, officials estimated the long-term demand for multi-family housing and the potential for new office space.

By all accounts, a plan was underway.

Green Line costs add, waiting for federal funding

By September 2014, officials realized it would cost the city more than half a billion dollars to extend the planned Green Line’s bus-only lanes to the South Health Campus and Country Hills Village, beyond the $625 million already pegged for the first phase of the transitway.

Calgary didn’t have enough money for the first phase, targeted for completion in 2021, which was set to offer specialized bus roads, bridges and bus-only lanes on existing streets from Centre Street and 78th Avenue North in Huntington Hills down to Douglas Glen Terminal in southeast Calgary.

Officials had to pivot, and planned to leave out a chunk of the southeast section — around Ogden and Riverbend — until it could secure $105 million in federal Building Canada Fund grants or other money.

By the end of 2014, the Green Line — at the time, a 40-kilometre LRT line that spanned the city and linked through a downtown tunnel — was seen as unobtainable due to its approximately $5-billion price tag.

Nenshi hopeful at hint of federal funding

The federal government, led by then-prime minister Stephen Harper, announced in 2015 a Public Transit Fund which promised $750 million over the first two years spread across the country, with a $1-billion annual fund by 2019.

Nenshi, who at the time was still the mayor of Calgary, hoped this would be a fund the city could potentially rely on to upgrade the planned Green Line route between the South Health Campus to Country Hills from a bus-only route into a low-floor CTrain link.

With the announcement of federal funding, council put forward a motion to extend the city’s commitment of $52 million per year from 10 years to 30 years, ultimately providing $1.5 billion toward the project.

Up to this point, the Green Line’s multibillion-dollar conversion to LRT had been forecast for the late 2020s or 2030s, with no reliable funding stream to deliver it.

Still in 2015, the city held public meetings to share options and development concepts for South Hill, Ogden, Lynnwood/Millican, 26th Avenue S.E. and Ramsay/Inglewood stations. Citizen input was to be used in development plans.

Additionally, the city held several Green Line Southeast public information sessions to “inform citizens about the upcoming engineering and design work to be done, land use studies to be conducted, and outline how interested citizens can be involved in the process,” according to the project timeline.

By April 2015, the Green Line Southeast Transitway was in its preliminary design stage, and council was to be asked to make a final decision in October.

Fabiola MacIntyre, a senior transportation engineer with the City of Calgary at the time, said it was hoped construction on the project would begin in 2017, with an opening date of 2021.

Debate over provincial funding continues

In July 2015, the federal Conservatives gave Calgary $1.53 billion to be used for the Green Line, ahead of a federal election call. Jason Kenney, Calgary MP and national defence minister at the time, announced the contribution.

Kenney maintained the timing of the cash infusion was appropriate for a fund announced just months earlier, in April, and not because of a looming federal election.

The announcement of the federal funding put pressure on the provincial NDP government, as did opposition parties.

In 2015, the Wildrose Party’s then finance critic Derek Fildebrandt said: “The Green Line is important infrastructure for Calgary and for southern Alberta and this is the kind of priority infrastructure that the Wildrose believes we should be focusing public expenditures on.”

Interim PC leader Ric McIver said the province shouldn’t waste an opportunity to partner with the federal government. McIver suggested building the project in stages if the province wasn’t ready to foot its share of the bill.

Nenshi pushed the provincial NDP government to make a decision by mentioning job creation. He anticipated 23,000 to be created between construction and operation of the Green Line.

Conversations of the Green Line being funded as a public-private partnership were brought up by advocacy group, Public Interest Alberta.

In September 2015, the provincial NDP government committed to $162 million to be spent on LRT electrical upgrades and bus rapid transit/transitway projects in Calgary’s south and north over seven years.

Brian Mason, transportation minister at the time, made the announcement but would not say if the province would commit any money specifically for Calgary’s Green Line LRT.

He did, however, say with oil prices remaining low and the NDP government on track to post a $6.5-billion deficit that year, it was unlikely the province would announce any funding for the Green Line in the near future.

In December 2015, Calgary city council was told the provincial government needed to contribute to the Green Line, or the city was at risk of losing federal funding.

Calgarians pay Green Line costs

Nenshi submitted an official request for funding for the Green Line LRT in January 2016.

A report to city council said funding for the project must be secured by October 2016 or construction of the train line could be broken up into stages. Nenshi needed both provincial and federal commitment, as the federal funding was first promised by the previous Conservative government but Liberals had since been elected into power.

Calgary homeowners faced a property tax increase in 2016 of nearly $170 on the average house as a result of the province’s annual property tax requisition, a 10.2 per cent increase from the previous year.

After facing backlash and resident complaints, city council decided to grant taxpayers a one-time rebate of the money on 2014 tax bills, before scooping up the annual tax room for 10 years to help cover a portion the city’s share Green Line LRT.

Feds, province to contribute $146 million

In December 2016, the federal and provincial government announced a contribution of $146 million for Calgary’s Green Line LRT, with the federal government committing to $1.5 billion.

“This funding brings us one step closer to beginning construction on the Green Line project,” Nenshi said at the time of the announcement.

“It’s also a show of commitment by all three orders of government to getting that Green Line project done.”

The joint funding announcement appeared to have removed any uncertainty remaining about the project’s completion.

While falling short of the overall funds needed, Nenshi said the province’s contribution to the Green Line is a step in the right direction.

Costs increase, construction delayed

By February 2017, officials estimated the cost of the Green Line LRT to exceed $6 billion, and the project to take longer to complete with construction set to begin in 2019.

At this point, the city has already spent approximately $101 million on the LRT project, with no official confirmation of provincial funding specific to the Green Line.

The provincial NDP government said it would not commit to its one-third share of the funding until the city was clear about the project’s cost and scope.

Nenshi and Keating, pioneers of the Green Line, were hopeful of the project’s success despite no dollar commitment for the project in the provincial budget.

By May 2017, the city’s transportation boss revealed the 46-kilometre Green Line LRT would be split into phases and the first segment — then-slated to open in 2026 — will stretch 20 kilometres and exceed the initial $4.5-billion estimate for the entire line.

Nenshi said the council’s design choices was the reason for the cost discrepancy.

City council approved the final alignment and 28 station locations for what was to be Calgary’s largest public works project — the multibillion-dollar, 46-kilometre Green Line LRT — in a 12-3 vote in June 2017.

By July the same year, then-premier Rachel Notley pledged $1.53 billion from the provincial carbon levy for Calgary’s Green Line LRT. The province’s funding was dedicated for the first phase of the project.

Leadership changes spark Green Line debates

In October 2017, Jyoti Gondek was elected as Ward 3 city councillor, saying the ward had previously been overlooked for the Green Line expansion. She said one of her priorities will be to start working on assembling the land along Centre Street to ensure the Green Line can eventually make its way north into far north-central Calgary.

Council argues north versus south for extension

In early 2018, city council argued strengths of a northern vs southern expansion of the LRT.

The Green Line project team told councillors that one of the strengths of the northern leg is the existing ridership, pointing out that 35,000 people used transit to cross the Centre Street Bridge each day. Coun. Sean Chu offered a more blunt argument on Green Line priorities. “The north should go first if we have extra money,” said the Ward 4 councillor.

An amendment from Gondek directed the city to look at ways to use existing Green Line land in the north for Bus Rapid Transit or other pedestrian and bicycle infrastructure.

Keating maintained his position on wanting the southern expansion.

A report came out in 2019 hinting that the future LRT line would only reach as far north as 64th Avenue N., disappointing Green Line advocates in the area.

Due to years of delays, expectations on when Calgary will see Stage 2, with further expansions, remained bleak.

In late 2018 as the city considered a ‘single-bore’ tunnel to reduce street-level disruptions during construction of the Green Line, some members of council raised concerns that the flow of information from the Green Line team had “gone silent.”

Then-councillor Druh Farrell of Ward 7 complained that it had been difficult to get a meeting with the Green Line team, and that after years of consultations with the public and councillors on this project, communication had stopped. Gondek agreed, while Keating downplayed concerns.

Green Line faces criticism, Calgary admits faults

In early 2019 Kenney, who had become leader of Alberta’s United Conservative Party, blasted the city for cutting the Green Line in half, wondering why the Green Line he had funded when involved in federal government was not being built.

The UCP leader took to social media to express concerns and complaints over the trajectory of the project.

At this point, a formal funding agreement had not yet been signed.

Keating admitted the project had fallen behind, and officials were trying to catch up.

Economists began criticizing the project in 2019, including concerns over the city’s liquidity and future costs as a result of Green Line construction in the wake of several other major projects.

A group of businessmen, helmed by veteran oilman Jim Gray, made an informal presentation to council’s transportation committee in 2019 urging a halt to spending and a one-year pause to carry out an in-depth review of the project.

Gray believed any stumbles on the project would bring the entire city down.

In 2020, Gray called the plan a “potential financial disaster.”

Shortly after Gray’s plea, then-councillor Evan Woolley put forward an urgent notice of motion asking for a comprehensive review before the city moves forward with the project, to ensure it aligned with the city’s current and future financial position.

These concerns initiated an independent review, without halting work.

By summer 2019, the city had split stage one into two parts. The plan was then for construction to begin in 2021 on the southern leg of the route, with work on the core held off until as late as 2022.

By December 2019, a council committee agreed to a delay on revealing route options for Green Line through downtown to give officials time to workshop the project.

Provincial funding concerns return

In late 2019, the new provincial UCP government announced its budget, delaying funds for transit projects. This would have forced the city to borrow more money, increasing interest payments.

The province sought to include a 90-day cancellation clause on its $1.53-billion in Green Line funding, leading the city to turn back to Ottawa for funding or face further delays.

In the midst of funding concerns and public distrust, the Green Line committee began to crumble. A 2019 committee meeting turned to in-fighting between members.

By the end of 2019, several council members were urging the city to nix spending for a planned new arena, and instead use that money for the Green Line LRT.

Green Line gets green light, then delayed by provincial review

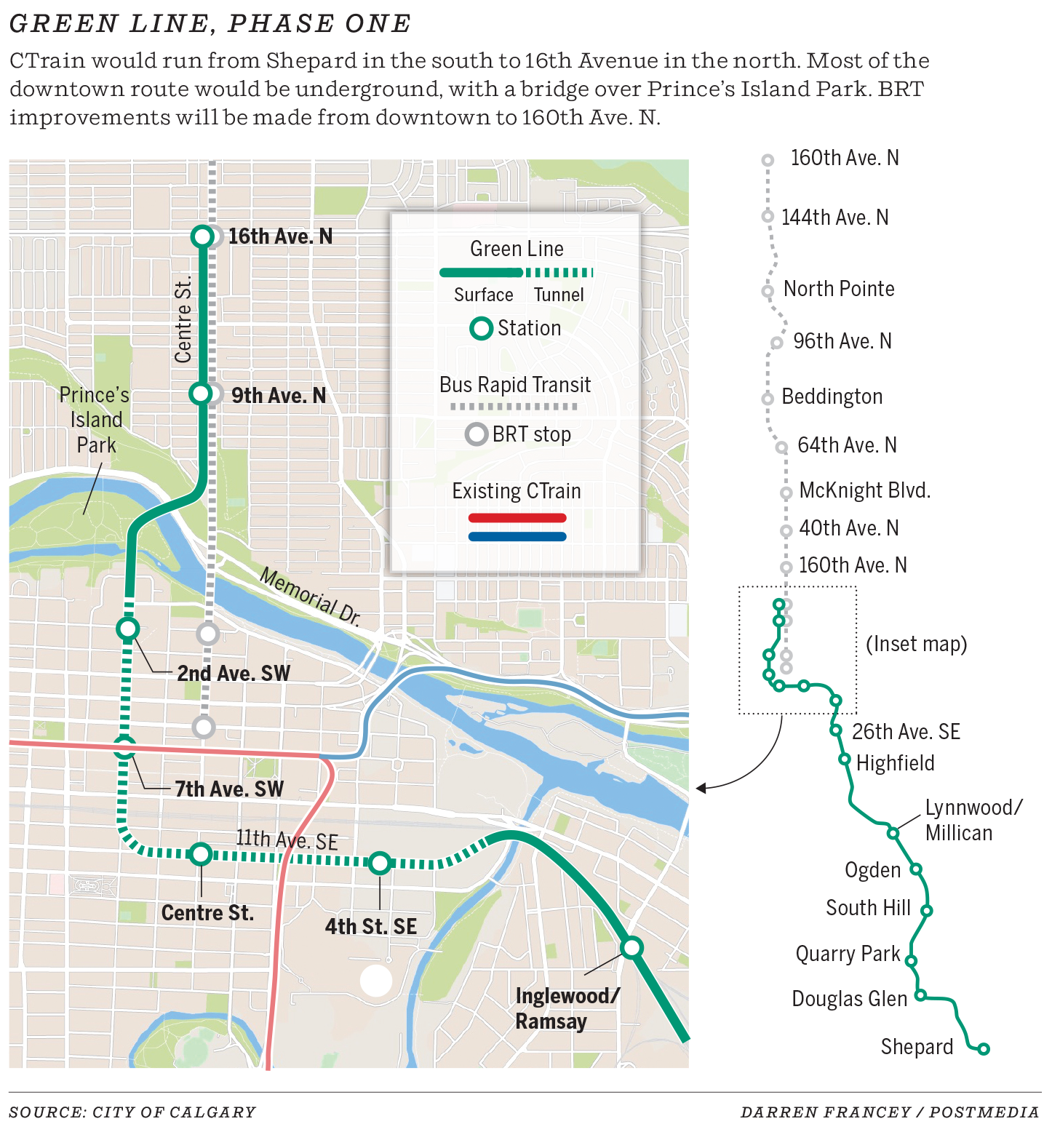

In a much-anticipated June 2020 vote, city council gave approval to the first stage of the Green Line, solidifying plans for a new LRT running from 16th Avenue N. to Shepard in the southeast.

At this point, the city had spent more than $550 million on the project, still anticipating a 2021 start and 2026 completion with an estimated total cost of $5.5 billion.

McIver publicly released a letter to Nenshi, acknowledging significant changes in cost and scope since the project’s initial announcement, and that the province must ensure the $1.53 billion it has committed to the Green Line is used responsibly.

The province also expressed willingness to revisit the 90-day cancellation clause, bringing hopes of provincial funding back on the table.

The Green Line committee spent much of 2021 under review by the UCP provincial government, followed by delays in hiring a company to build the first piece of the project. By June 2021, there was no date for when construction could start.

Keating anticipated the UCP review delay would delay the project by one to two years.

Once the review was approved, McIver called the project “a massive investment in the future of Calgary,” acknowledging that the provincial government finally had faith in the Green Line.

Darshpreet Bhatti was appointed as CEO of the project in 2021, saying his major concern was more delays.

By January 2022, more than $680 million had been spent on the project.

Shortly after, in March, the city was in talks of starting Green Line construction in Ogden, with work expected to begin in summer of 2023.

The Green Line LRT comes to an end

Concerns ramped up again in March 2024, when city council members were told costs were expected to escalate.

Bhatti told councillors the Green Line’s budget was determined before the COVID-19 pandemic, and inflationary pressures have affected the market for infrastructure projects since then.

Shortly following that, a UCP cabinet minister indicated the province no longer supported the project, and the city considered transferring management to the Alberta government.

— With files from Postmedia