The gig economy is largely comprised of newcomers, experts say — an industry that’s becoming increasingly untenable for workers due to unpredictable and minimal income

In the two years since he moved to Calgary with his wife and two kids, Walid’s lone priority has been survival.

The oil and gas engineer, who moved from the Gulf region two years ago to escape geopolitical instability, started off in the city by filling his days with a continuum of jobs that could help support his family.

Up daily at 6 a.m., he’d work for three hours in the garage doing odd jobs tuning up neighbours’ cars. Once the kids were sent to school, he’d spend the next five to six hours delivering food on Uber Eats, sometimes pulling in just $4 per trip. To finish his day, Walid spent a number of hours doing small jobs at an auto mechanics’ shop, ending around 9 or 10 p.m.

“Hustling and doing all this, it’s good for survival — but you are surviving at the minimum,” said Walid, who declined to provide his full name. And living in Calgary has been more expensive than he expected. “I was shocked with the financial cost of living overall.”

“Everything is gone. Vanished,” he said.

‘The income is both very low and very unpredictable’

It’s a situation some experts say is emblematic of challenges the gig economy presents to Calgarians using it as a source of income — an industry specifically popular among newcomers attempting to lay roots in Canada.

The numbers show gig work has increasingly become the sector of choice for many Albertans and Canadians, too: In December, close to half a million Canadians used a digital platform or app that paid them for their work. In Alberta, about five per cent of the province’s entire workforce is doing gig work as their main job — the highest proportion among Canadian provinces, according to Statistics Canada’s Labour Force Surveys in 2022 and 2023.

App-based employment has become an accepted feature of Canada’s economy since it rose in prominence about a decade ago — particularly given its flexible work hours and efficient road to employment.

Even so, the intervening years have put a drag on the sector’s public image and it has become a target for labour advocates. Tenuous income and a lack of regulation have resulted in criticism that companies are freely able to take advantage of workers who are trying to make ends meet, even despite the flexible work hours it offers.

“The income is both very low and very unpredictable and in many cases, people aren’t even making minimum wage,” said Jim Stanford, economist and director at the Centre for Future Work.

Protections for gig workers introduced in some provinces

One-hundred per cent of customers’ tips will also go to the worker, workers will be covered through B.C.’s workers’ compensation agency and they will receive a 35- to 45-cent per-kilometre vehicle allowance, according to the new regulations.

Labour groups have applauded the move but said there’s more that should be done, noting that gig workers still won’t be compensated for time spent between jobs.

Gavin McGarrigle, western regional director for Unifor, said B.C.’s new regulations take a positive step forward, but accessing collective bargaining remains nearly impossible in all Canadian provinces.

“If you’re going to work as an Uber driver in Calgary, you are completely at the mercy of your company,” McGarrigle said.

Companies rarely impose limits to how many people can work for them at a given time, McGarrigle said. That means the several dozen Uber drivers who protested their working conditions in February at Calgary airport were either representing a majority or small minority of Calgary drivers.

“If they have no idea what the number of workers are, then how can they ever organize?” he said.

In B.C., unions are automatically certified if 55 per cent of employees support the move. But without imposing limits to the number of employees working for a given company, employees are prevented from organizing, McGarrigle said. Without that ability, he said, workers are therefore dependent on governments to act on their behalf.

To date, the Alberta government has expressed minimal interest in taking steps similar to B.C.

In response to questions regarding whether Alberta is considering reforms in the sector, such as creating a minimum wage for gig workers, the province said it “continues to review information on how labour laws may affect this sector.”

“Changes to labour laws for this sector may have significant impacts for service providers and workers and Alberta’s government would consider these impacts before making any changes,” Marisa Breeze, press secretary to Minister of Jobs, Economy and Trade Matt Jones, wrote in a statement to Postmedia.

Diana Palmerin-Velasco, senior director of the future of work at the Canadian Chamber of Commerce, said in an interview that provinces should be careful of applying blanket regulations on the sector such as applying labour classifications, which is a major gap for some gig workers and unnecessary for others such as owner-operators in the trucking industry.

“This idea of blanket regulations … could be incredibly dangerous because that would be detrimental to workers themselves,” Palmerin-Velasco said.

She said she’s on side with ensuring workers earn 100 per cent of their tips and that companies are transparent with their pay practices, but she doesn’t see other regulations being helpful.

Alberta’s rapidly growing population a factor in gig economy

However, it also said there’s a need for “careful intervention” in the area of gig work, as the government will have to balance developing greater labour protections without limiting the opportunities presented by the economy.

Alberta’s high proportion of gig workers is likely a symptom of the province’s rapidly growing population, Stanford said.

“It’s a very tough job, but people do it out of desperation, and that’s why Alberta has a slightly higher proportionate number of platform workers … Alberta’s labour market reflects that pool of desperate workers,” he said.

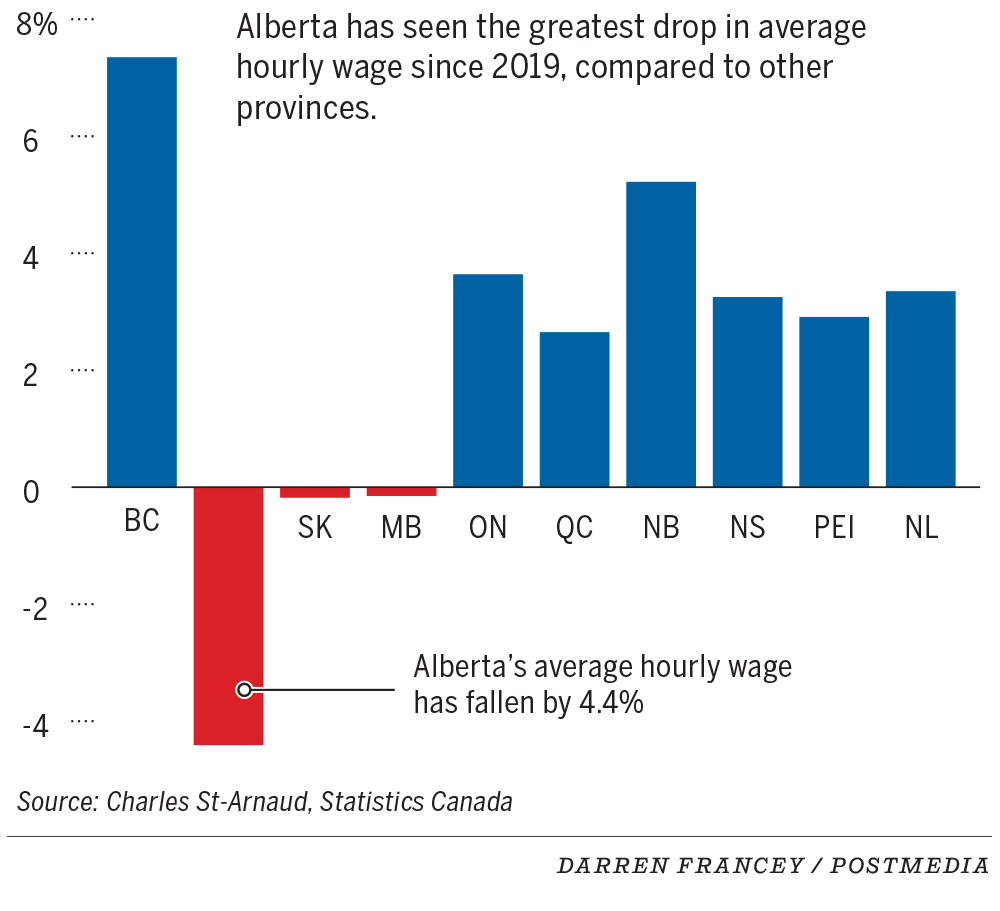

Stanford argued that the sheer size of Alberta’s gig economy, specifically on platforms such as Uber and Skip The Dishes, points to an “indication that labour conditions in Alberta have been deteriorating for a decade.”

After a year under his rotation of three jobs, Walid pivoted last year to seek education. With his wife taking up employment at an evening school to allow him to study, he’s training to become a heavy equipment mechanic through Momentum, an organization that helps with skills training for low-income Calgarians. He’s currently studying physics, chemistry, math and English in preparation for his exam.

Two years into his time in Calgary, Walid expressed surprise at how long it’s taken to get settled in the city.

“I was thinking I would face some issues, especially for a job,” he said. “I’m trying to struggle and survive, but I didn’t expect it to take that long.”

This week: The Cost of Doing Business

Read more from the series:

- ‘This is a homeless shelter!?’: A single mother’s journey through homelessness in Calgary

- ‘The business of generating yield for shareholders’: Why rents are going up so fast in Calgary

- ‘It’s depressing being a 40-year-old stuck at home’: Why the dream of homeownership is fading for many Calgarians

- Dream home or one-bedroom condo? What will $700,000 buy you in housing markets across Canada

- Rising rents: what $2,000 a month will get you in major Canadian cities right now