‘What’s interesting over time is the way governments have responded to that.’

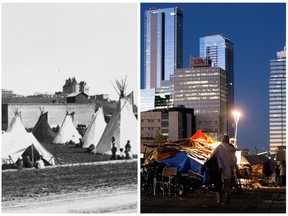

Over a century ago, as many as one in four Edmontonians lived in tents.

The figure comes from Harvey Voogd, vice president of the North Saskatchewan River Valley Conservation Society board, who gleaned them from city archives.

Looking at a 1907 survey by the Edmonton Bulletin newspaper, combined with local population figures from 1906, the percentages are startling.

“We are talking 25 to 30 per cent of the population was living in tents,” Voogd said. “What’s interesting over time is the way governments have responded to that.”

Many people tented back then for the same reasons influencing houselessness now, including a tight market and soaring prices, he said.

Some of the places the unhoused clustered may strike a familiar chord. These include Riverdale, Cloverdale, Oliver, behind the Dreamland Theatre on Jasper Avenue, and east of 95 Street near the Canadian Northern Railway tracks (between 104 and 105 Avenues).

Edmonton city council reacted to the rise of temporary dwellings by passing Bylaw 121 in 1907.

You could tent, but only if you bought a one-time licence for a dollar.

That’s about $32 in today’s inflated values.

Failing to comply with the bylaw would get you a fine of up to to $5, which would be more than $150 these days.

“These tents would then be known by health officials and would have to conform to the local health code,” explained Voogd.

“It makes sense: we want to know you exist and you’re disposing waste property.”

One historic picture from city archives shows a 1906 “tent house” — more like a yurt, with what appears to be about a seven-foot by 10-foot canvas structure overtop a wood and metal frame and floor, complete with canvas and wood door. A metal stovepipe vented woodsmoke.

In another sepia-toned photo of a tent home, a gentleman wearing a coat and tie sits in a rattan-looking easy chair, reading a paper, while a woman appears to be standing and doing kitchen work.

“For Pleasure, for Economy and for Inability to Secure Other Quarters — Almost a Fifth of Edmonton’s Population Lives Under Canvas. Not An Unpleasant Experience,” a Bulletin headline read.

A tale of two tent cities

In 1894, a dump took hold on the river valley’s north bank, right where the Edmonton Convention Centre and Louise McKinney Park sit now.

The Grierson Dump housed a community of unhoused single men, uprooted from drought-struck farms and immigrant families.

Some had seasonal harvest work, or else scavenged, retooled and sold objects they found.

Home was where the salvaged materials were — a piece of tin, a few odd boards, newspaper for insulation, heat from coal dug out from the hillside.

By 1932, city archives show, medical health officer Dr. R. B. Jenkins raised concerns that river water used by dump inhabitants included sewer contamination.

Cases of typhoid fever heightened alarm.

By 1938, evictions were underway.

Another tiny tent town emerged between 1935 and 1937, at 142 street, north of Stony Plain Road.

This one was mostly whole families, and mostly First Nations or Metis. Similar to today’s debates, there was controversy over who should take responsibility for the residents.

According to the archives, Mayor Joe Clarke was told most of the families had lived there for a considerable time, the homemade shacks were clean and tidy for the conditions, and they didn’t interfere with neighbours.

Chief Const. A.G. Shute of city police took an unsympathetic tone, recommending the dwellers be relocated outside the city and become the responsibility of the province.

Chief health inspector W.R. Graham gave 14 families two weeks to leave, recommending the federal government take charge of their welfare.

The General Superintendent of Indian Agencies told Clarke the residents were outside of federal jurisdiction, being Métis and non-treaty First Nations.

The area was evicted summarily, without fanfare or newspaper attention.

Descended from tenting people

If your forebears came to Alberta among the early settlers, chances are decent they lived in a tent for a time. Or a sod hut, dugout or lean-to, if they were a bit luckier.

After publishing a newsletter story of tenting in Edmonton a century ago, Voogd received some emailed responses.

A man named Roger told him of great-grandparents arriving in Edmonton from New Zealand in 1905.

“My grandmother told me they spent their first winter in a tent at the foot of Groat ravine. Quite a difference from the South Pacific,” he wrote. “They survived in tough conditions much the same way our less fortunate citizens do now.

“Kudos to that original spirit and independence that I see in full blossom now, despite overwhelming prejudice continually expressed against the less fortunate.”

In the days following the Second World War, living rough was still a thing.

Teresa emailed Voogd about her parents, who came to Alberta in 1948.

Her mother ended up working for free on a farm near Daysland, about 140 km southeast of Edmonton, to pay back their sponsor.

“My father was trying to find work in Edmonton. He had no home, so he slept in the river valley. He would cover himself with newspapers. There were many who did,” she wrote.

Many people over Edmonton’s history have made their start in what would now be considered living rough circumstances, Voogd said.

“Their children and grandchildren are living with us today.”